Can what you eat determine how long, and how well, you live? The clinically proven answer is yes, and The Longevity Diet is easier to follow than you'd think. The culmination of 25 years of research on ageing, nutrition, and disease across the globe, this unique combination of an everyday diet and fasting-mimicking diet (FMD) to be done only 34 times per year lays out a simple solution to living to a healthy old age through nutrition.

FMD does away with the misery and starvation most of us experience while fasting and helps you reap all the beneficial health effects of a restrictive diet while avoiding the negative stressors, like low energy and sleeplessness.

Valter Longo, Director of the Longevity Institute at USC and the Program on Longevity and Cancer at IFOM in Milan, developed the FMD after making a series of remarkable discoveries in mice and humans indicating that specific diets can activate stem cells and promote regeneration and rejuvenation in multiple organs to reduce the risk for diabetes, cancer, Alzheimers and heart disease. Longo's simple pescatarian daily eating plan and the periodic, fasting-mimicking techniques can both yield impressive results. Low in proteins and sugars and rich in healthy fats and plant-based foods, The Longevity Diet is clinically proven to help you:

Longos healthy, life span-extending plan is based on an easy-to-adopt pescatarian plan along with the fasting-mimicking diet 4 times a year, and just 5 days at a time. Including 30 easy recipes for an everyday diet based on Longo's five pillars of longevity, The Longevity Diet is the key to living a longer, healthier, and fulfilled life.

The contents of this chapter must not be used in self-diagnosis or the self-administration of therapies. This information is intended for medical professionals following your disease.

[For their review of this chapter, I thank Hanno Pijl, endocrinologist, diabetologist, and director of the Clinic for Endocrinology and Metabolic Disease at Leiden University, and Clayton Frenzel, bariatric surgeon.]

Type 2 Diabetes

Type 2 diabetes, by far the most common of the two types, affects more than 27 million people in the United States; an additional 86 million people have prediabetes, meaning they have elevated risk factors for diabetes. According to the World Health Organization, the number of people diagnosed with diabetes globally has more than quadrupled in the past thirty-five years, from 100 million in 1980 to 422 million in 2014. The disease is diagnosed by measuring the average level of glucose in the blood (by an HbA1c test), or by detecting glucose levels above 125 mg/dL after an overnight fastthis latter measure is known as ones fasting glucose level. Typical symptoms include high thirst, frequent urination, blurry vision, irritability, numbness of the hands or feet, and fatigue.

In type 2 diabetes, the pancreas produces insulin, but muscle cells, liver cells, and fat cells do not respond properly to it. When cells become insulin-resistant, glucose accumulates in the blood. You can think of insulin as the key needed to unlock the gate that lets glucose enter the cells, but also the key that closes the door that allows glucose to be released by the liver. In type 2 diabetic patients, that key isnt working properly, the gate doesnt open completely, and glucose cannot enter cells at the normal rate.

But the damage to normal cells begins well before diabetes is diagnosed. People who are obese or overweight with high levels of abdominal fat have a far greater chance of developing diabetes and prediabetes (when fasting glucose levels are between 100 and 125 mg/dL).

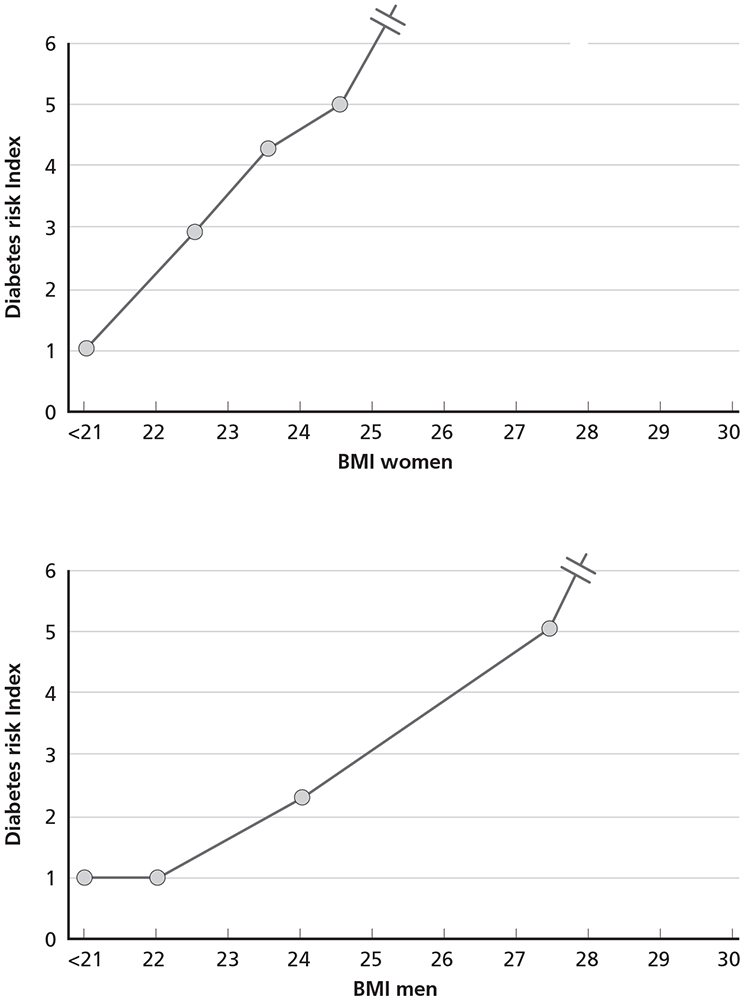

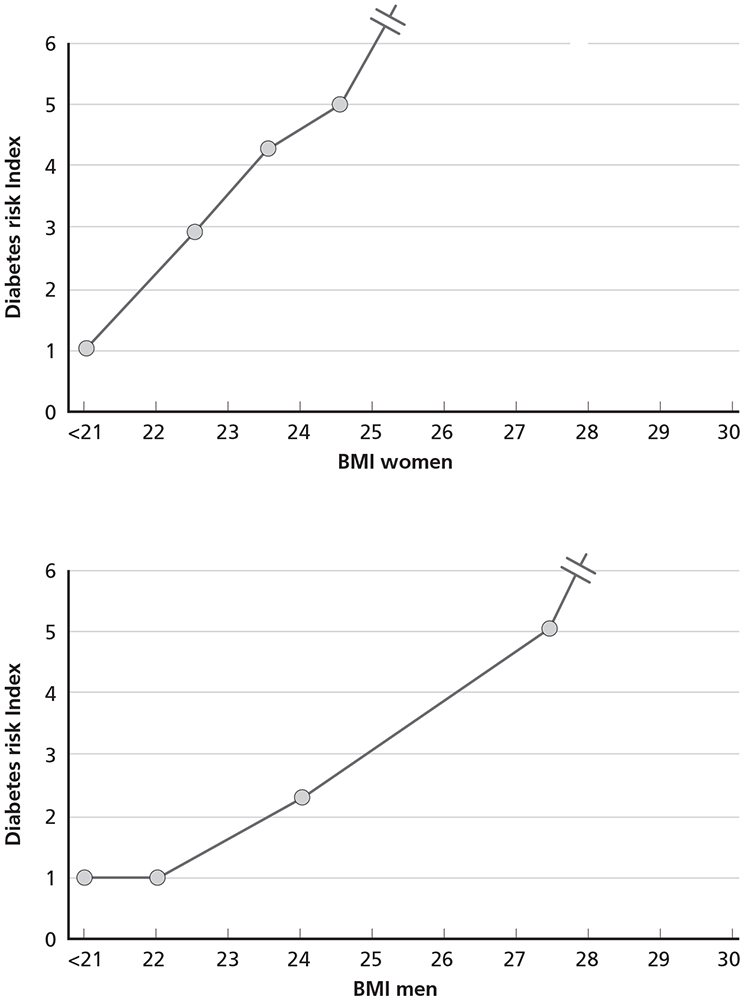

The risk for diabetes is sixfold higher among women with body mass index (BMI) of 25 than those with a BMI of 21. For a five-foot-five-inch-tall woman, this is the difference between weighing 154 pounds and 130 pounds. A similar effect is observed in men with a BMI of 27.5 and 22, which indicates that a five-foot-eight-inch-tall male weighing 152 pounds would have a risk for diabetes that is five times lower than that of a man of the same height weighing 191 pounds (see

8.1. Diabetes onset risk increases with higher body mass index

Another study indicates the best way to assess risk for diabetes is by measuring abdominal fat via waist circumference. Men with a waist measurement above forty inches and women with a waist measurement above thirty-four inches are at the highest risk.

Nutrition, Weight Management, and Diabetes Prevention

Maintaining an ideal weight will minimize the chance of developing diabetes. We know from both human and monkey studies that a severely calorie-restricted diet can either completely prevent diabetes, as in monkeys, or, as in humans, cause such a dramatic reduction in fasting glucose levels and abdominal fat that it would be highly unlikely that these individuals would develop diabetes.

However, the great majority of people cannot maintain a 30 percent calorie-restricted diet, and dont want to give up most of the foods they enjoy; nor should they want to lose large quantities of muscle mass or become too thin, which would be unavoidable after prolonged calorie restriction. Also, several studies indicate calorie restriction does not reduce fasting glucose among obese people the same way it does among people starting from a normal weight. To prevent diabetes, then, it is important to identify strategies better suited to a majority of people.

In the following section, I present both the everyday dietary changes and the periodic fasting-mimicking diets that can be adopted to prevent and help reverse diabetes.

The Longevity Diet for Diabetes Prevention and Potential Reversal

Adopting the Longevity Diet described in can help prevent and has the potential to reverse diabetes in some subjects. Not only will it help you maintain or reach a healthy weight and abdominal fat levelespecially when combined with the exercise guidelines in chapter 5but also it may reduce diabetes incidence independently of weight. Here are specific dietary interventions that can help prevent and treat diabetes:

1. Eat within twelve hours or fewer per day.

In

This technique can be adjusted to further regulate weight. For example, if limiting food intake to eleven to twelve hours per day isnt sufficient, it can be limited to ten or even eight hours per day (8 a.m. to 6 p.m., or 8 a.m. to 4 p.m.), although limiting the food intake period to less than eleven to twelve hours could have side effects including gallstones. However, restricting food intake to an eleven- to twelve-hour window every day is often observed in very long-lived populations, so this more permissive time frame is probably a safer choice until further studies become available.

2. Be nourished: eat more, not less, but better.

As discussed in , if you ate 5.3 ounces of pasta or pizza with 5.3 ounces of cheese, you could be consuming 1,100 calories in a relatively small portion that is deficient in important vitamins and minerals. If you instead ate 1.4 ounces of pasta (about 140 calories) and an additional 14 ounces of garbanzo beans (about 330 calories) plus 11 ounces of mixed vegetables (about 210 calories) and 0.5 ounce of olive oil (about 120 calories), you would reach only 800 calories, while eating a large portion rich in proteins, healthy fats, complex carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals.