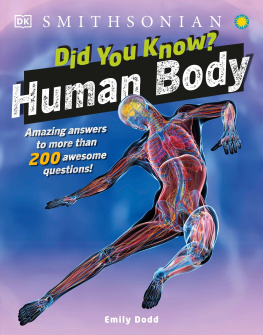

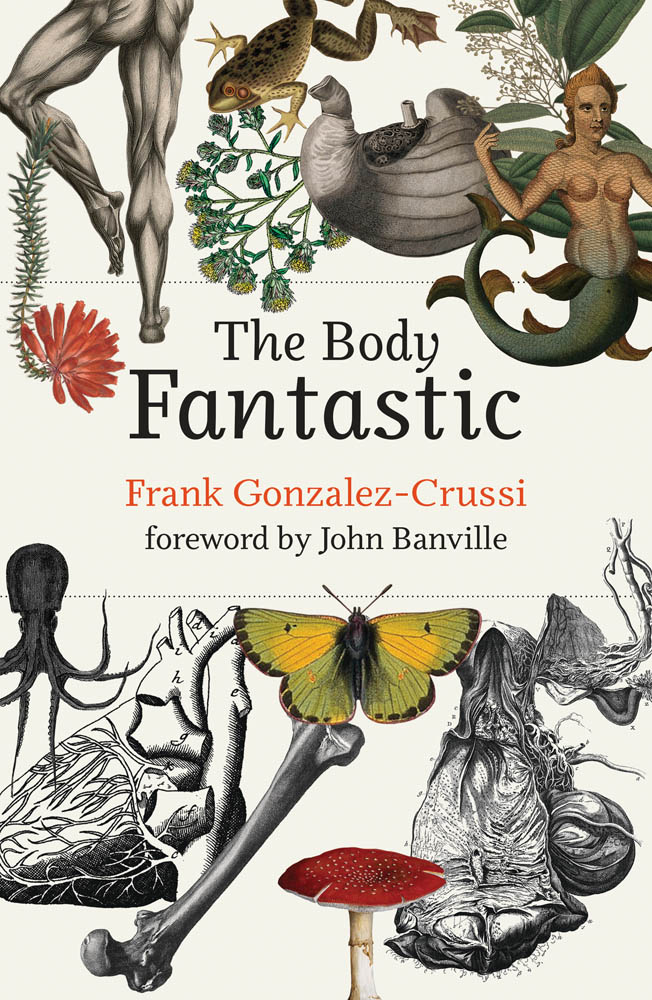

The Body Fantastic

The Body Fantastic

Frank Gonzalez-Crussi

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2021 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Gonzalez-Crussi, F., author.

Title: The body fantastic / Frank Gonzalez-Crussi.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The MIT Press, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020037092 | ISBN 9780262045889 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Human anatomyHistory. | Human anatomy in literature. | Human body in literature. | Human bodyMythology. | Human bodyFolklore. | Human body (Philosophy) | MedicineHistory.

Classification: LCC QM11 .G67 2021 | DDC 611dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020037092

d_r0

Contents

by John Banville

There are numerous aspects of his character and thought on which Ren Descartes may be commended, not least his well-known predilection for cross-eyed women, but his assertions on dualism and the mindbody debate have proved nothing short of catastrophic for humankind. How are we to give this sheath of flesh in which we are encased its proper due if its nothing more than an automaton, an elaborate wax figure, dead in itself and worked only by the minds invisible wires, as Descartes in his wisdom taught?

In the Western religio-philosophical tradition, Plato and St. Paul, to name but two influential haters of the flesh, had already done much to make the earthly body seem a trivial, annoying, and even disgusting appendage of the divine soul: Gods practical joke upon the creatures whom, so the priests tell us, he fashioned in his own image.

Indeed, given Christianitys reprehension of the merely physical, it is a question as to why at the Second Coming it is necessary that we should be returned to corporeality. Surely the angels will snigger at us behind their hands as, in our newly reconstituted bodies, we mill about up there in post-Resurrection Paradise, helpless in our trillions, as closely packed as passengers on a rush-hour commuter train, though this one will be infinitely long and will have no destination.

Nietzsche made every effort to restore the bodys reputation, insisting always on its equal value in the mindbody equation. His Zarathustra tells us there is more wisdom in your body than in your deepest philosophy, and, warming to the task, suggests that once the soul looked contemptuously upon the body, and then that contempt was the supreme thing:the soul wished the body lean, monstrous, and famished. Thus it thought to escape from the body and the earth. But that soul was itself lean, monstrous and famished...

And recall the Reverend Sydney Smyth, that delightful, irrepressible, ever wise, witty and mischievous clergyman philosopher, who in a sermon enjoined his congregation to keep ever in mind the fact that, since God is omnipresent, he inhabits not only the soul of man but also that part upon which man, and woman, necessarily sit. This, we may say, surely is a fundamental truth.

Frank Gonzalez-Crussi is a champion of the body in all its prosaic as well as its mysterious manifestations. He has spent his adult life studying it, as a pathologist and academic and, starting in mid-career, as a writer. He is also an antiquarian and an omnivorous readerfor evidence of his scholarship, take a glance through his notes and list of sources for The Body Fantastic.

His precursors include the Roman physician and philosopher Galen of Pergamon; Sir Francis Bacon, First Viscount St. Albans, one of those who transformed the natural philosophy of the ancients into what we know as science, and who according to John Aubrey died of pneumonia contracted while seeking to deep-freeze a chicken by stuffing it with snow; Sir Thomas Browne, scholar and supreme prose stylist, the author of, among other notable works, the splendidly titled Pseudodoxia Epidemica, or Vulgar Errors; and Robert Burton, who sought to cure his own sick spirit by writing The Anatomy of Melancholy, an enormous work of which he produced no fewer than five revised and expanded editions in his lifetime. We might also cite as a fellow member of the brotherhood of the arcanum Gonzalez-Crussis Latin American neighbor, Jorge Luis Borges.

It was from a poet, indeed a poet philosopher, that Gonzalez-Crussi had his initial inspiration for this book. Paul Valry, he tells us, set out in his essay Rflexions simples sur le corps the proposition that we inhabit not one but four bodies. First is the one in which we live our quotidian lives, second, the one that others see, third, the inner, biological body made up of organs, and fourthalthough Valry only glances at this possibilitywhat might be designated the quantum body, the one that has its flickering, liminal existence within the swirl of particles and probabilities that the quantum scientist will tell us is the real world.

The Body Fantastic is a cabinet of curiosities, a Wunderkammer fully worthy of the Emperor Rudolf II, that would have been much appreciated by Sir Thomas Browne, in particular, whose Hydrotaphia, or Urne BuriallLife is a pure flame, and we live by an invisible Sun within ussuffers not at all from the fact that the funerary urns which are the starting point for his magnificent essay were not ancient Roman artifacts, as he thought, but Anglo-Saxon in origin.... As we see, the urge to veer off and ramble happily down side tracks, as our author loves to do, is catching. But what is duller than a straight road?

Valrys fourth body, as the poet himself writes, and as Gonzalez-Crussi quotes, is no more or less distinguishable from the subatomic spume in which it has its being than is a whirlpool from the liquid in which it is formed; an insubstantial thing, an ethereal entity, Gonzalez-Crussi suggests, immersed in an atmosphere made of history, symbolism, myths, legends, tales, mental representations, desires, fears and hopes. However, this patchwork mantle that so neatly wraps us round and so diligently shields us from harsh winds and killing frosts is as integral to us as is the thinking mind.

The dream of flying by the bodys nets into the free, clean, and luminous realm of pure, unfettered being is as old as Gilgamesh, and is the basis of all religions. But would this really be a desirable state in which to pass our lives? To live is to be in the world, which is the bodys home, cluttered, ramshackle, and ever in need of repair though it may be. We persist in living, as Rilke beautifully writes in the Duino Elegies,

because being here is much, and because all this

thats here, so fleeting, seems to require us and strangely

concerns us. Us the most fleeting of all.

Gonzalez-Crussi takes a measure of the body from top to toe, calling on a host of witnesses as inquisitive, open-minded, and wide-ranging in their interests as he is himself. And there are some surprises, such as Casanova, a remarkable individual of profound erudition and, you will be startled to know, something of a feminist, as Gonzalez-Crussi demonstrates in some judiciously chosen passages from the Venetian savants writings.

We are introduced also to scores of lesser-known figures, all of them fascinating in their colorful ways. In the first paragraph alone of his chapter on the stomach, the author calls to our attention a miniature gallery of English eccentrics. There is the Cornishman Robert Stephen Hawker, an Anglican priest who excommunicated his cat for catching mice on Sundays; John Mad Jack Mytton, who kept two thousand pet dogs and who once arrived for dinner at a friends house riding on the back of a bear; and the Reverend Dr. William Buckland, theologian, paleontologist, and zoophage extraordinaire, who styled himself the man who ate everything, and to whom, it was said, Noahs Ark looked like a dinner menu.

Next page