The Illusion of Control

Why Financial Crises Happen, and What We Can (and Cant) Do about It

Jn Danelsson

Yale UNIVERSITY PRESS

New Haven & London

Published with assistance from the Louis Stern Memorial Fund.

Copyright 2022 by Jn Danelsson.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Galliard type by Newgen North America.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021948855 ISBN 978-0-300-23481-7 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Acknowledgments

Several friends and colleagues made invaluable contributions to the book. I borrowed many arguments from joint work with Charles Goodhart, Kevin James, Robert Macrae, Andreas Uthemann, Marcela Valenzuela, Ilknur Zer, and Jean-Pierre Zigrand.

I had the privilege of consulting several experts, including Peter Andrews, formerly of the FCA, Jon Frost at the Bank for International Settlements, risk system expert Rupert Goodwin, fund manager Jacqueline Li, Eric Morrison from the FCA, physicist Donal OConnell, and three lawyers: Gestur Jonsson, Haflii Kristjn Lrusson, and Eva Micheler.

I was fortunate to employ several excellent London School of Economics (LSE) students to assist me on background research for the book: Sophia Chang, Jia Rong Fan, and Morgane Fouche. Our manager at the Systemic Risk Centre, Ann Law, was very helpful in getting the book under way. The many drawings in the book were made by two excellent artists, Lukas Bischoff and Ricardo Galvao.

Without all of these people, this book would not have seen the light of day.

I am grateful to the Economic and Social Research Council (UK), grant number: ES/K002309/1 and ES/R009724/1, and the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (UK), grant number EP/P031730/1, for their support.

Riding the Tiger

The man who didnt trust the models saved the world.

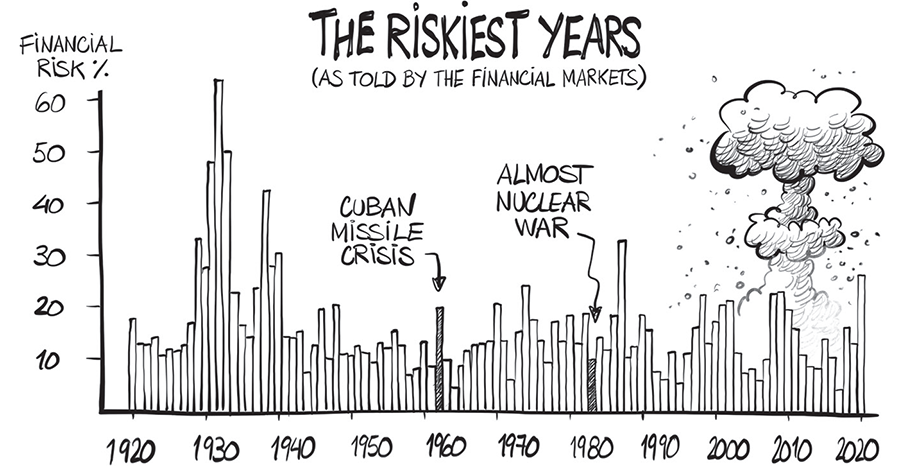

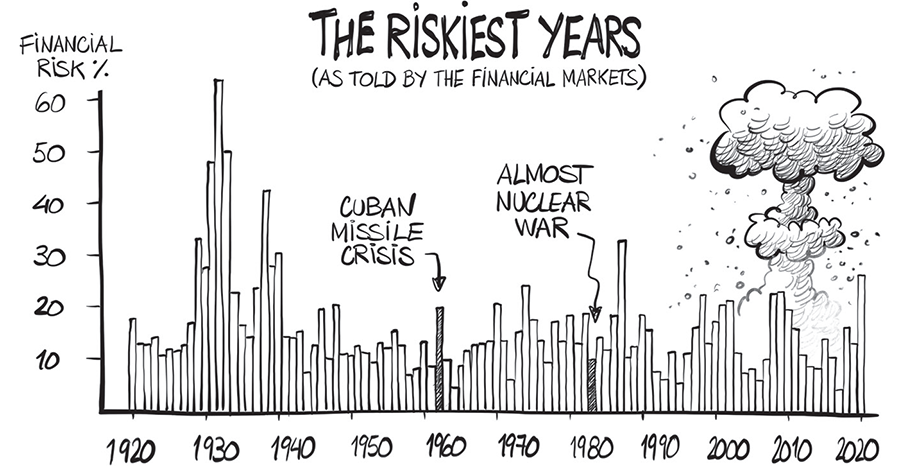

Figure 1. Credit: Copyright Ricardo Galvo.

Almost every economic outcome we care about is long term. Pensions, the environment, crises, real estate, education, you name it, what matters is what happens years and decades hence. Day-to-day fluctuations dont matter to most of usthe short run isnt very important. So it stands to reason that the way we manage our financial lives should emphasize the long run. But by and large, it doesnt. We are good at managing todays risk but at the expense of ignoring the promises and threats of the future. That is the illusion of control.

A quick test. What do you think are the riskiest years of the past century? Covid in 2020? The global crisis in 2008? The Great Depression in the 1930s? Lets ask the financial markets and their go-to measurement of ).

But these are not the riskiest years by a long shot. In 1962 and 1983 we were almost hit by the ultimate tail event, even though the financial markets remained calm. The Cuban missile crisis nearly brought the United States and the Soviet Union to blows in 1962, only for the Soviets to back down at the last minute. Even more interesting is 1983 because that is when we almost got into a nuclear war, even if we didnt know that until much later.

What happened was that the premier of the Soviet Union, Yuri Andropov, got it in his head that the United States was planning to launch a preemptive nuclear strike. He instructed his spies to find evidence supporting his suspicion, and KGB agents everywhere went into overdrive, looking for that evidence. Careers depended on it. If you have a choice of a juicy posting in Washington or being literally sent to Siberia (as the KGB rep in Novosibirsk) of course you find proof. A prime example of confirmation bias. We believe something terrible will happen and find grounds to support that, even if there is no truth to it. In 1983 the early warning models of the Soviet Union detected a nuclear attack. The man on watch that night, Stanislav Petrov, didnt trust the signal and decided unilaterally not to launch a counterattack. The man who didnt trust the models saved the world. The Soviet investigators subsequently confirmed he was right. The false alarm came about because of a rare alignment of sunlight on high-altitude clouds above North Dakota and the Molniya orbits of the detection satellites. Colonel Petrov died in 2017, by that time globally recognized for having saved humanity.

The way we measure financial risk today, with what I call the riskometer, has much in common with Andropovs early warning systems. Both rely on imperfect models and inaccurate measurements to make crucial decisions. While high-altitude clouds bedeviled the Soviets models, the problem for todays riskometer arises from its emphasis on the recent past and short-term risk. The reason is simple. That is the easiest risk to measure, as the modelers have plenty of data.

The problem is that short-term risk isnt all that important, not for investors and especially not for the financial authorities. For them, what matters is systemic risk, the chance of spectacular financial crises, like the one we suffered in 2008. Long-term threats, like systemic crises or our retirement not being as comfortable as hoped for, are easy to understand, at least conceptually. Take crises. Banks have too much money and cant find productive investments, so they start lending to increasingly low-quality borrowers, often in real estate. In the beginning it looks like magic. Money flows in, developers build houses, and everybody feels rich, encouraging more lending and more building in a happy, virtuous cycle. Then it all comes crashing down.

What are we to do? Regulation, of course, using the Panopticon. An idea dating to the eighteenth-century English philosopher Jeremy Bentham, who proposed regulating society by setting up posts to observe human activity. Does it work? In traffic certainly. If no police or cameras monitor speeding, I suspect many will be tempted to drive too fast. The chance of getting caught keeps the roads relatively safe. Surely we can also employ the Panopticon to regulate finance and so prevent crises and all the horrible losses. We do use it, but it doesnt work all that well. The reason has to do with the interplay of two complex topics, the difficulty of measuring risk and human ingenuity.

Unlike temperature or prices, risk cannot be directly observed. Instead, it has to be inferred by how prices have moved in the past. That requires a model. And as the statistician George Box had it, All models are wrong, but some are useful. There are many models for measuring risk, they all disagree with each other, and there is no obvious way to tell which is the most accurate. Even then, all the riskometers capture is the short term because that is where the data is.

And then we have human behavior. Hyman Minsky observed forty years ago that stability is destabilizing. If we think the world is safe, we want to take on more risk, which eventually creates its own instability. And since the time between decisions and bad things happening can be years or decades, it is hard to control risk. As my coauthor Charles Goodhart put it, Any observed statistical regularity will tend to collapse once pressure is placed upon it for control purposes. What Goodharts law tells us is that when the risk managers start controlling risk, we tend to react in a way that makes the risk measurements incorrect.