Praise for David E. Hoffmans

The Dead Hand

A stunning feat of research and narrative. Terrifying.

John le Carr

The Dead Hand is a brilliant work of history, a richly detailed, gripping tale that takes us inside the Cold War arms race as no other book has. Drawing upon extensive interviews and secret documents, David Hoffman reveals never-before-reported aspects of the Soviet biological and nuclear programs. Its a story so riveting and scary that you feel like you are reading a fictional thriller.

Rajiv Chandrasekaran, author of

Imperial Life in the Emerald City: Inside Iraqs Green Zone

The Dead Hand is deadly serious, but this story can verge on pitch-black comedyDr. Strangelove as updated by the Coen Brothers.

The New York Times

In The Dead Hand, David Hoffman has uncovered some of the Cold Wars most persistent and consequential secretsplans and systems designed to wage war with weapons of mass destruction, and even to place the prospective end of civilization on a kind of automatic pilot. The books revelations are shocking; its narrative is intelligent and gripping. This is a tour de force of investigative history.

Steve Coll, author of Ghost Wars and The Bin Ladens

[A] taut, crisply written book. The Dead Hand puts human faces on the bureaucracy of mutual assured destruction, even as it underscores the institutional inertia that drove this monster forward. A fine book indeed.

T. J. Stiles, Minneapolis Star Tribune

An extraordinary and compelling story, beautifully researched, elegantly told, and full of revelations about the superpower arms race in the dying days of the Cold War. The Dead Hand is riveting.

Rick Atkinson, Pulitzer Prize-winning

author of An Army At Dawn

No one is better qualified than David Hoffman to tell the definitive story of the ruinous Cold War arms race. He has interviewed the principal protagonists, unearthed previously undiscovered archives, and tramped across the military-industrial wasteland of the former Soviet Union. He brings his characters to life in a thrilling narrative that contains many lessons for modern-day policy makers struggling to stop the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. An extraordinary achievement.

Michael Dobbs, author of One Minute to Midnight:

Kennedy, Khrushchev, and Castro on the Brink of Nuclear War

DAVID E. HOFFMAN

The Dead Hand

David E. Hoffman is a contributing editor at The Washington Post and author of The Oligarchs: Wealth and Power in the New Russia. He lives in Maryland.

www.thedeadhandbook.com

Also by David E. Hoffman

The Oligarchs: Wealth and

Power in the New Russia

To My Parents

Howard and Beverly Hoffman

CONTENTS

Science has brought us to a point at which we might look forward with confidence to the conquest of disease and even to a true understanding of the life that animates us. And now we have cracked the atom and released such energies as hitherto only the sun and the stars could generate. But we have used the atoms energies to kill, and now we are fashioning weapons out of our knowledge of disease.

Theodor Rosebury, Peace or Pestilence:

Biological Warfare and How to Avoid It, 1949

PROLOGUE

I. Epidemic of Mystery

Are any of your patients dying? asked Yakov Klipnitzer when he called Margarita Ilyenko on Wednesday, April 4, 1979. She was chief physician at No. 24, a medium-sized, one-hundred-bed hospital in Sverdlovsk, a Soviet industrial metropolis in the Ural Mountains. Her hospital often referred patients to a larger facility, No. 20, where Klipnitzer was chief doctor. Klipnitzer saw two unusual deaths from what looked like severe pneumonia. The patients, he told Ilyenko, were two of yours. No, Ilyenko told him, she did not know of any deaths. The next day he called again. Klipnitzer was more persistent. You still dont have any patients dying? he asked. Klipnitzer had new deaths with pneumonia-like symptoms. Who is dying from pneumonia today? Ilyenko replied, incredulous. It is very rare.

Soon, patients began to die at Ilyenkos hospital, too. They were brought in ambulances and cars, suffering from high fevers, headaches, coughs, vomiting, chills and chest pains. They were stumbling in the hallways and lying on gurneys. The head of admissions at Hospital No. 20, Roza Gaziyeva, was on duty overnight between April 5 and 6. Some of them who felt better after first aid tried to go home. They were later found on the streetsthe people had lost consciousness, she recalled. She tried to give mouth-to-mouth resuscitation to one ill patient, who died. During the night, we had four people die. I could hardly wait until morning. I was frightened.

On the morning of April 6, Ilyenko raced to the hospital, threw her bag into her office, put on her white gown and headed for the ward. One patient looked up at her, eyes open, and then died. There are dead bodies, people still alive, lying together. I thought, this is a nightmare. Something is very, very wrong.

Death came quickly to victims. Ilyenko reported to the district public health board that she had an emergency. Instructions came back to her that another hospital, No. 40, was being set up to receive all the patients in an infectious disease ward. The word spreadinfection!and with it, fear. Some staff refused to report for work, and others already at work refused to go home so as not to expose their families. Then, disinfection workers arrived at hospital No. 20, wearing hazardous materials suits. They spread chlorine everywhere, which was a standard disinfectant, but the scene was terrifying, Ilyenko recalled. There was panic when people saw them.

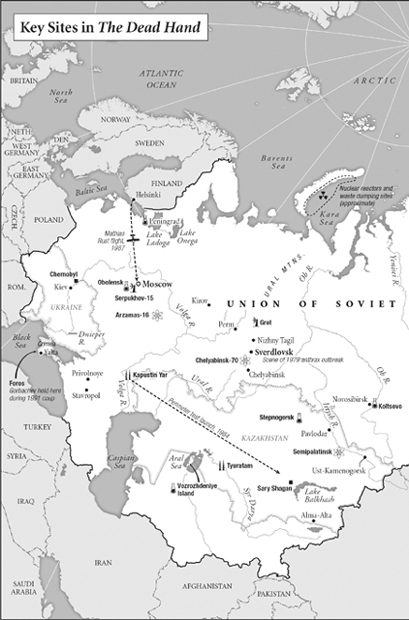

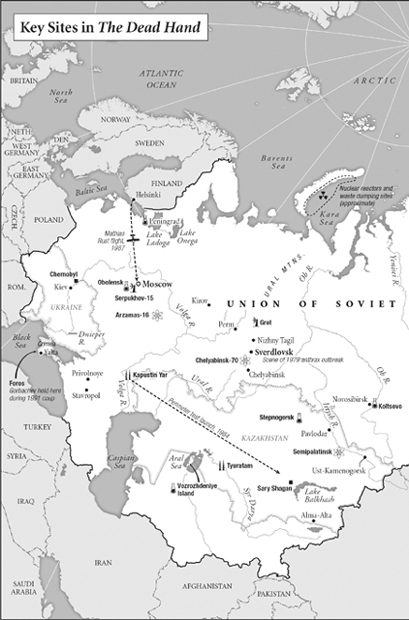

Sverdlovsk, population 1.2 million, was the tenth-largest city in the Soviet Union and the heartland of its military-industrial complex. Guns, steel, industry and some of the best mechanical engineering schools in the Soviet Union were Sverdlovsks legacy from Stalins rush to modernize during World War II and after. Since 1976, the region had been run by a young, ambitious party secretary, Boris Yeltsin.

Hospitals No. 20 and 24 were in the southern end of the city, which slopes downward from the center. Streets lined with small wooden cottages and high fences were broken up by stark five-story apartment buildings, shops and schools. The Chkalovsky district, where Ilyenkos hospital was located, included a ceramics factory where hundreds of men worked in shifts in a cavernous building with large, high windows.

Less than a mile away, to the north-northwest, was Compound 32, an army base for two tank divisions, largely residences, and, adjacent to it, a closed military microbiology facility. Compound 19, which comprised a laboratory, development and testing center for deadly pathogens, including anthrax, was run by the 15th Main Directorate of the Ministry of Defense. On Monday April 2, 1979, from morning until early evening, the wind was blowing down from Compound 19 toward the ceramics factory.