Contents

Guide

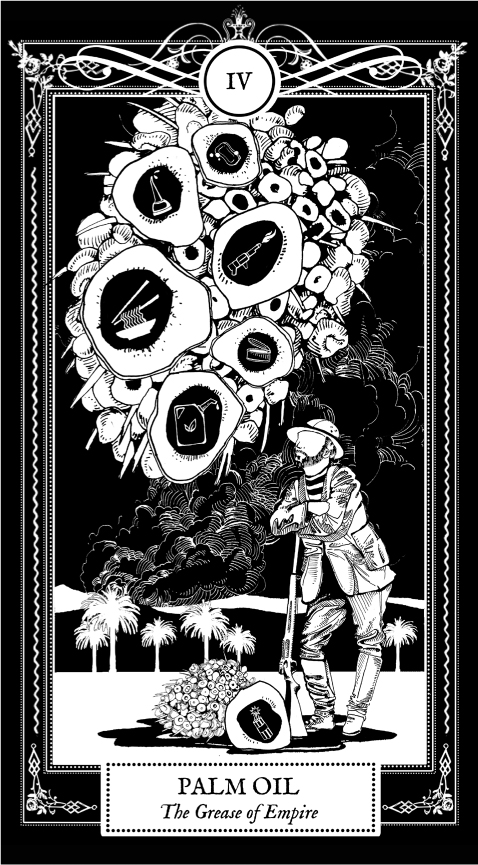

Palm Oil

Radical pamphlets to fan the flames of discontent at the intersection of research, art and activism.

Series editor: Max Haiven

Also available

001

Pandemonium: Proliferating Borders of Capital and the Pandemic Swerve

Angela Mitropoulos

002

The Hologram: Feminist, Peer-to-Peer

Health for a Post-Pandemic Future

Cassie Thornton

003

We Are Nature Defending Itself: Entangling Art, Activism and Autonomous Zones Isabelle Fremeaux and Jay Jordan Published in collaboration with the Journal of Aesthetics & Protest

Palm Oil

The Grease of Empire

Max Haiven

First published 2022 by Pluto Press

New Wing, Somerset House, Strand, London WC2R 1LA

www.plutobooks.com

Copyright Max Haiven 2022

The right of Max Haiven to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 0 7453 4582 6 Paperback

ISBN 978 0 7453 4586 4 PDF

ISBN 978 0 7453 4584 0 EPUB

This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin.

Typeset by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England

Simultaneously printed in the United Kingdom and United States of America

Contents

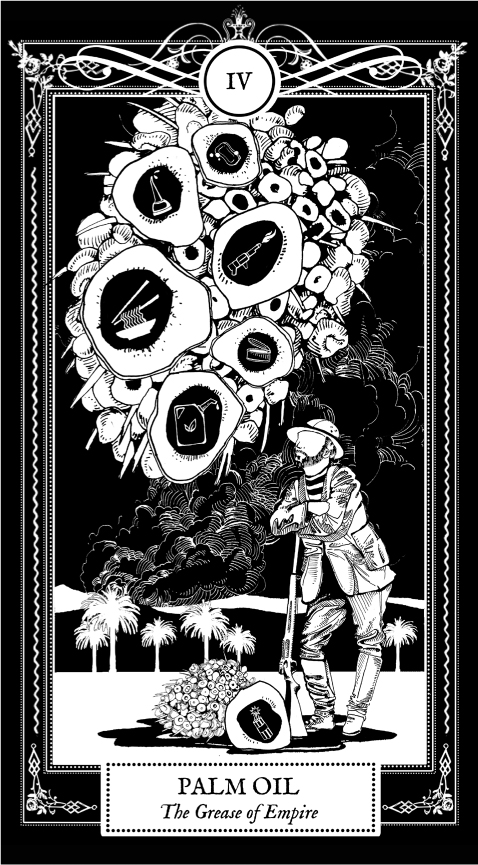

Artist: Amanda Priebe

Whose grease?

We find ourselves in a system of racial capitalism that appears as a vast, globe-spanning system of mystified human sacrifice, hidden in plain sight. The stories of palm oil I want to tell you will trace this systems contours and seek answers in its past. These are a story of how one largely invisible thing emerged from the nexus of capitalism, colonialism, and empire to define the cruelties of our world. Secreted within it is a story of our collective power to transform the world for the better. The story of palm oil is our story. This almost magical and ubiquitous substance is part of the way our bodies reproduce themselves and the way our material world is reproduced. It is a key element in the vortex of labor, commodities, meaning-making, and social relationships that make up the world in which we both live. Palm oil binds us, revealing the space in between, the syntax of the world.

Nearly every element of the process that now finds you reading these words could have been touched or facilitated by palm oil: it could be an additive in the paper, a stabilizer in the ink, or part of the resin in the binding of the book; it is almost certainly either inside or essential to the manufacture of one of the hundreds of the components of the digital electronic device on which I am typing these words, and on which you might be reading them. Its probable that one of the transport vehicles that conveyed these artefacts to you burned hydrocarbons that included palm oil-derived agrofuels. And it must be taken as given that the body and brain that writes and that reads has been reproduced, in part, through the metabolism of palm oil. We have both used palm oil products to clean or care for our skin. We have ingested palm oil as a carrier of medicines. Though I suspect neither of us are intentionally investors in the palm oil industry, we are nonetheless economically entangled with it. The money that we receive for our labor is blood in the same ocean. Though it derives from a natural source, we created refined palm oil as it exists today, and it has, in turn, helped to created us.

In the story of palm oil, we can catch a glimpse of the world as it is made and unmade. To read a world of palm oil as if it were our story is to recognize what connects us and what divides us. My hope is that in paying attention to palm oil we might exercise some shared narrative muscle, so long atrophied in this world of competitive individualism, so that some we emerges that can better know itself and act in concert to change our fate. If we made this world from palm oil, what else could we have made? What else might we yet make?

In the past, my work has been dedicated to trying to grasp what we dont understand about capitalism. We understand that it is a global system that organizes the energies of humans and non-humans toward the production of commodities in the interests of profit. We understand that it has given birth to the structure of the corporation, that terrifying metahuman entity that magnifies our worst qualities (avarice, indifference, rapaciousness). We understand that capitalism arose entangled with colonialism and racism and has never survived without them. Elsewhere, I have tried to understand how, today, in a global capitalist economy dominated by debt and credit, we are all compelled or seduced into transforming ourselves into competitive risk takers, miniature financiers, leveraging all aspects of our lives as assets and gambits to secure our individuated futures.

In this short book I am trying to understand something that is abundantly obvious and yet somehow also unseeable: this system seems to be a vast and merciless organization of human sacrifice. Unlike the sensationalist images of that bloody custom, which has been practiced by many of the worlds civilizations though under very different circumstances, the global capitalist order of human sacrifice is one that denies itself. The relentless logic of the market insists that the millions of needless deaths from malnutrition, toxic poisoning, overwork, sabotaged migration, climate chaos, or neo-imperialist wars are somehow accidental, incidental, or inevitable. But my wager is that, in telling a story of palm oil, we can recognize that we live in what Ruth Wilson Gilmore calls the age of human sacrifice. And we can see how it emerges from a longer history of racial capitalism that makes some people vastly more susceptible to disposability than others.

By palm oil I am speaking of the derivative of specific palm plants, mostly Elaeis guineensis, the African oil palm, but also sometimes cultivated from its central American relatives, Elaeis oleifera and the more distant Attalea maripa. Oil palms are among the worlds most bountiful and useful plants. E. guineensis, from which we get most of the worlds palm oil, is native to West Africa, where people have cultivated and treasured it for centuries. From its marvelous saffron-colored seedpods (which, when ready to harvest, can weigh over 10kg) African people have for millennia derived not only cooking oil but also lamp oil, cosmetics, medicines, artistic materials, sacraments, and dyes. From its sap comes palm wine and a wide variety of remedies. From its leaves come roof thatching and arrow and spear shafts. Yesterday and today, fragrant, fleshy, palm oil has served ceremonial and spiritual purposes in Africa and its diaspora. For many, red, virgin palm oil is the taste of home, the taste of family, the taste of history.