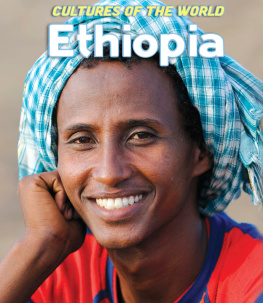

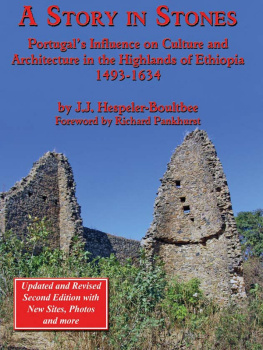

Introduction

In putting forward a second edition of my Highlands of Ethiopia, I have two very different duties to perform: first, to thank the press for the extremely liberal and generous manner in which it has received my work; secondly, to reply to certain objections which have been made by one or two periodicals, happily not of the first eminence, against both me and my travels. So numerous, however, are the publications that have evinced a favourable, I might almost say a friendly, disposition towards me, that I am unable to specify them. They will, therefore, I trust, accept in general terms my thanks to them one and all.

Their very flattering testimonies have induced me to revise carefully what I have written, in order, if possible, to render it worthy of their warm praise, and to justify their predilection in my behalf. On the other hand, fas est et ab hoste doceri. I have consequently turned to account even the animadversions of my enemiesfor enemies unhappily I have, and those, too, of the most implacable and malignant charactermean persons to whom I have shown kindness, which they have apparently no means of repaying but by inveterate aversion. This circumstance I ought not perhaps to regret, except on their account. The parts we play are suitable to our respective characters; and I should even now abstain from prejudicing them in the estimation of the public, if I did not apprehend that my forbearance might be misconstrued.

The points of attack selected by my adversaries are not many in number. Ultimately, indeed, they resolve themselves into three: first, my style of composition, which they say is gorgeous and inflated, and therefore obscure; second, the inaccuracy of several of my details; and third, the absence of much new information, which it seems the public had a right to expect from me. On the subject of the first accusation it will not perhaps be requisite that I should say much. To any one who cannot understand what I write I must necessarily appear obscure; but it may sometimes, I think, be a question with which of us the fault lies. That my composition is generally intelligible may not unfairly, I think, be inferred from the number of persons who have understood and praised it; since it can scarcely be imagined that the majority of reviewers would warmly recommend to the public that in which they could discern no meaning. Besides, on the subject of style there is a great diversity of opinion, some thinking that very extraordinary scenes and objects should be delineated in forcible language, while others advocate a tame and formal phraseology which they would see employed on all occasions whatsoever. I may observe, moreover, that style, as Gibbon remarks, is the image of character, and it is quite possible that my fancy may have a natural aptitude to take fire at the prospect of unusual scenes and strange manners. Still I am far from defending obstinately my own idiosyncracies, and yet farther from setting them up as a rule to others. In describing what I saw, and endeavouring to explain what I felt, I may very possibly have used expressions too poetical and ornate; but the public will, I am convinced, do me the justice to believe that, in acting thus, my object was exactly to delineate, and not to delude. I called in to my aid the language which seemed to me best calculated to reflect upon the minds of others, those grand and stupendous objects of nature which had made so deep and lasting an impression on my own. At all events, I am not conscious of having had in this any sinister purpose to serve.

It is a far more serious charge, that I have presented the public with a false account of the Embassy to Shoa; that I have altered or suppressed facts; that I have been unjust to my predecessors and companions; and that I have at once misrepresented the country and its inhabitants. It has been already observed, that my accusers are few in number. Probably they do not exceed three individuals, two who affect to speak from their own knowledge, and one whom they have taken under their patronage as their cats-paw. It may seem somewhat humiliating to answer such persons at all. I feel that it is so. But if dirt be cast at me, I must endeavour to shield myself from it, without enquiring whether the hands of the throwers be naturally filthy or not. That is their own affair. Mine is to avoid the pollution aimed at me. This must be my apology for entering into the explanations I am about to give.

When I undertook to lay before the public an account of my travels in Abyssinia, I had to choose between the inartificial and somewhat tedious form of a journal, and that of a more elaborate history, in which the exact order of dates should not be observed. I preferred the latter; whether wisely or unwisely remains to be seen, though hitherto public opinion seems to declare itself in favour of my choice. Having come to this determination, it was necessary that I should act in all things consistently with it. As I had abandoned the journal, it was no way incumbent on me to observe the laws which govern that form of composition. My business, as it appeared to me, was to produce a work with some pretensions to a literary character; that is, one in which the order of time is not regarded as a primary element, the principal object being the grouping of events and circumstances so as to produce a complete picture. I perfectly understood that I was to add nothing and to invent nothing, but that I was at liberty to throw aside all trivial details, and dwell only on such points as seemed calculated to place in their proper light the labours of the mission, with the institutions, customs, and type of civilisation found among the people to whom we had been sent. In conformity with this theory I wrote. One of the first consequences, however, of the view I had taken of my subject, was the sacrifice of all minute personal adventures, which scarcely appeared in any way compatible with my plan. I abandoned likewise the use of the first personal pronoun, and always spoke of myself and my companions collectively, thereby perhaps doing some little injustice to my own exertions, but certainly not arrogating to myself any credit properly due to others. Among my friends there are those who object to this manner of writing, and I submit my judgment to theirs. In this Second Edition, therefore, I have reconstructed the narrative so far as was necessary in order to convert the third person into the first. To the charge that I have not observed the strict chronology of a journal, I have already pleaded guilty. It seemed to me far better to arrange together under one head whatever belonged properly to one topic. For example, when recording the medical services rendered to the people of Shoa, high or low, I have not inserted in my work each individual instance as it occurred, but have placed the whole before the reader in a separate chapter. So likewise in other cases, that which appeared to elucidate the matter in hand, was introduced into what I thought its proper place, because there it might both receive and reflect light, whereas in any other part, perhaps, of the work, it might have been without significance, if not altogether absurd. Not being infallible, I may possibly have misinterpreted the laws of rhetoric which I adopted as my guide: of this let the public be judge. I have aimed, at all events, at drawing a correct outline of Shoa and the surrounding countries, as far as my materials would permit, and should I have sometimes fallen into error, I claim that indulgence which is always readily extended to authors similarly circumstanced. While in Abyssinia, my official position very greatly interfered with my predilections as a traveller. I could not move hither and thither freely. To enlarge the circle of science was not the principal object of my mission; but at the same time it must not be forgotten that I enjoyed some advantages which a traveller visiting the country under other auspices would scarcely have commanded. In drawing up my work, however, the character in which I travelled was of considerable disservice to me. Much of the information that I collected, it was not permitted me to impart, which I say, not by way of complaint against the regulations of the service in which I have the honour to be engaged,on the contrary, I think it most just and proper that such should be the casebut that the reader, when he feels a deficiency in political or commercial information, may know that it has not been withheld through any negligence or disrespect of the public on my part.