The Star and Celebrity Confessional

In this book the different manifestations, meanings, and processes of the star and celebrity confessional will be explored. The confessional is taken to be any moment in which a star, celebrity, or fan engages in revelatory acts that are considered to be authentic, heart-felt, and honest. These confessional encounters can take place in an interview, through performance and presentation events, online, and in unscripted encounters. A star may break down in tears, or reveal a previously unknown truth about their private life. However, this authenticity is often found to have been manufactured, or is timed to occur against a new release or product launch. Alternatively, the desire to confess may be seen to draw attention to the centrality of pseudo forms of emotion in contemporary culture and the obsessional behaviour it produces. In this book authors consider acts of confession by celebrities such as Tom Cruise, Michael Jackson, Jade Goody, Britney Spears, Sarah Jessica Parker, Tracey Emin, and Russell Crowe.

This book was previously published as a special issue of Social Semiotics.

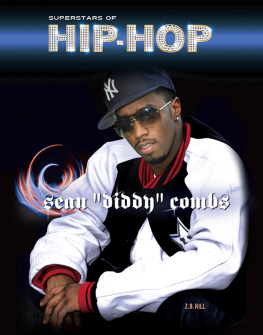

Sean Redmond is Senior Lecturer in Film at Victoria University of Wellington. He is editor of Celebrity Studies, and co-editor of Framing Celebrity: New Directions in Celebrity Culture (Routledge, 2006). He is presently working on the monographs Celebrity and the Media, and Emotional Celebrity.

First published 2011

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2011 Taylor & Francis

This book is a reproduction of Social Semiotics 18.2. The Publisher requests to those authors who may be citing this book to state, also, the bibliographical details of the special issue on which the book was based.

Typeset in Times New Roman by Taylor & Francis Books

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN13: 978-0-415-61454-2

Disclaimer

The publisher would like to make readers aware that the chapters in this book are referred to as articles as they had been in the special issue. The publisher accepts responsibility for any inconsistencies that may have arisen in the course of preparing this volume for print.

I confess

I confess the fact that I feel the need to, feel compelled to, let you know about the secrets that lie hidden within. Everywhere I look I see and hear people confessing, telling, revealing, and opening-up to others designated as councillors, healers, empathizers and readers of the guilty self. Everywhere I cast a glance or an ear I witness confessor and confessed to engage in revelatory communication. Countless magazines, television shows, books, educational pamphlets, records, films, art exhibitions, chat rooms, and weblogs hail me through the emotive language of the confessional. Speak up, tell all, let go, I am implored. This incitement to discourse (Foucault 1979, 19) asks me to confess about sex, adultery, polygamy, deviancy, criminality, desires, hopes, failings, memories, crimes, feelings, traumas, self-worth, wounds, pleasures, interests, duplicities, wrong-doings, faith, politics anything and everything that impacts on the wellness of the individuated self in Late Capitalist society.

People who reveal all are rewarded for their candid honesty they are healed, exalted, promoted, and sexually, psychologically and physically liberated from that which, although it had existed in the silent interior of the self, had eaten away at their living being. I confess that confessing makes me, helps me feel better about myself; and that in witnessing others confess, I believe I gain unmediated access to the trials and tribulations that lie at the heart of the human condition. I am ontologically more secure in a world ordered, regulated by honest council. I confess and the world heals me, and my confession heals others. When I confess I look to tomorrow with hope.

I confess that the confessional drives me into the public arena, so that the private becomes a forgotten locale, a shadowy zone where I should no longer reside (Furedi 2003). In this shadowy zone, criminals, paedophiles, and terrorist cells lie in silent wait to wreck havoc on the open, democratic world where good people live. When the Other confesses they do so with an appetite for destruction, to champion a foul deed, or because, under interrogation or cross-examination, they were forced, coerced, punished and disciplined into confessional submission. Their revelatory whispers are often accompanied by the cries wrung from torture. Post 9/11, one only has to think of the Abu Graib interrogation photographs to connect the confessional with the control and humiliation of the human body (Agamben 1996).

I confess loudly, emotionally, and sometimes violently, because in doing so I may be granted access to the media centre. At the very least I will be able to confess in a mediagenic arena, on a television studio stage, in a magazine, on You Tube, or in a taped confession I send to the BBC with regards to some heinous crime I have committed. I confess because it may grant me (temporary) celebrity status.

Stars and celebrities confess they always have invested in the revelatory mode of self-enunciation but in the self-reflexive, ubiquitous, highly simulated environment of 24/7 media culture today, they centrally rely on the confessional to authenticate, validate, humanize, resurrect, extend and enrich their star and celebrity identities. Stars and celebrities confess, and in so doing confirm their status as truthful, emotive, experiential beings who as devotional fans we can invest in.

In Sam Taylor Woods photographic exhibition Crying Men (20022004), she captures a number of male film stars involuntarily crying. With each photograph, the viewer is presented with a seemingly private, intimate moment of sorrowful emotion. The authentic self of the actor revealed, with only the fragments or traces of the star image left behind. It is as if the real person has opened themselves up, and one has access to their interior self and some enigmatic pain or trauma they had held secretly within. For example, in the photograph of Daniel Craig (2003), we see his hand in the process of wiping away the stream of tears that has reddened his eyes, and wet his face. With his elbows on his knees, leaning forward, Craig looks an emotional wreck. His red eyes return the viewers gaze, and in the intimate relationship created by such direct address, Craig cries to/for/with the imagined individual caught looking at him. The photograph reverberates with emotional intensity. It is deeply, affectively moving. However, at the same time, with the knowledge that Craig is an actor, a question emerges of whether what the viewer is witnessing (feeling) is an insight into his confessional soul, or the moving execution and capture of another acting role. In each and every celebrity confessional such a doubt emerges, but in the scanning, excavating, pawing, detailed looking and interrogation of the revelation we search for the authentic moment. We search for truth.