First published 2006 by Transaction

Publishers Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2006 by Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2006040431

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Redfield, Robert, 1897-

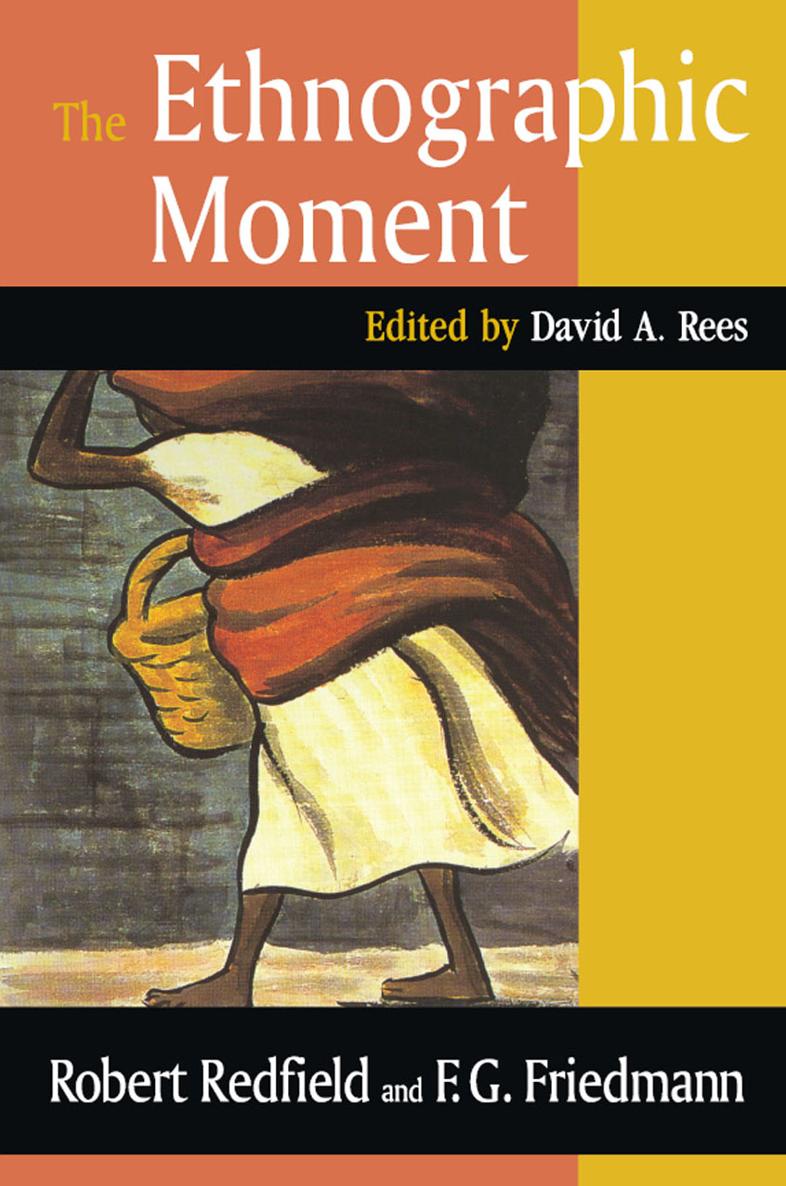

The ethnographic moment : correspondence of Robert Redfield and F. G. Friedmann / edited by David Rees.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 0-7658-0333-X

1. Redfield, Robert, 1897- Correspondence. 2. Friedmann, Fredrich Georg, 1912Correspondence. 3. Peasantry. I. Rees, David, 1979-II. Title.

HD1521.R43 2006

305.5633dc22

2006040431

ISBN 13: 978-0-7658-0333-7 (hbk)

By the beginning of the 1950s, cultural anthropology had discovered the peasant. The first fifty years of the century had witnessed the development of American ethnographic work from the salvage work of professionals affiliated with museums, who undertook to document with artifacts and testimony the threatened traditional way of life among the Native American tribes, to the establishment of anthropology as a science, represented in university departments, that sought to describe the ethnographic present of isolated primitive peoples, often in distant parts of the world. Robert Redfield, while himself a leading figure in this paradigm shift, also challenged anthropologys focus on a static model of the isolated primitive community by pointing out the dynamic nature of the little communities he studied in Mesoamerica. These were not static, isolated communities, but rather local, traditional cultures located well within the sphere of influence of a complex urban culture. In order to describe a great tradition deriving from urban centers in distinction to and interaction with the little tradition of surrounding local cultures, Redfield identified a need for anthropology to refer to areas of knowledge special to disciplines such as theology, philosophy, history, economics, and sociology. After all, the fieldworker could not simply halt his observations when the peasant heard a sermon from an educated priest, sold his grain to an urbanized merchant at the market, or otherwise interacted with representatives of a sophisticated great tradition.

Together with the study of the complex contacts between great and little traditions, Redfield sought valid ways of describing world views, or fundamental values, in particular among peasants. This interest in values and outlooks, which Redfield, together with his colleague at Chicago, Milton Singer, was pursuing in the early 1950s, represents the conceptual conclusion of anthropologys evolution from the collection of artifacts to a concern with the immaterial realm of values and ideas. Yet the study of fundamental values and viewsitems that, unlike artifacts, cannot be measured or collectedtraditionally belonged to soft sciences such as philosophy, psychology, and religion. Thus, their study by anthropologists, who at that time considered themselves hard scientists, obviously required a new, special kind of approach; especially in the peasant world, where the rural community cannot be considered independently of the influences of urban sophistication, such an approach would have to rely on interdisciplinary references. As Redfield put it in 1955 in a series of lectures he gave at Swarthmore College, anthropologys turn from (putatively) isolated, autonomous communities to little communities living in the shadow of great traditions called for new thoughts and new procedures of investigation. For studies of villages, it [this turn] requires attention to the relevance of research by historians and students of literature, religion, and philosophy. It makes anthropology much more difficult and very much more interesting.1

The collection of essays and previously unpublished papers in the present volume tells the story of a remarkableand hitherto almost unknownchapter in Robert Redfields pioneering efforts on what was then an anthropological frontier. The volume complements the existing collections of Redfields letters and papers by filling a gap. The printed letters of Redfield and Sol Tax, who was first Redfields student, then colleague at the University of Chicago, end in 1946;2 the present book covers the important years from 1952 to 1958the last of Redfields lifeand thus shows Redfield from a valuable new perspective. Moreover, while the two-volume collection of Redfields papers published postumously in 19623 does include papers showing the development of Redfields ideas on peasant communities (including one essay reprinted here), the present volume, focusing on this particular area of Redfields interests, introduces much valuable archive material that has, until now, been absent from the record.

At the core of the present volume lies the correspondence between Redfield and F. G. Friedmann, which, lasting from February 1952 until April 1958, played an important role in developing the formers conceptualization of the peasant world. Friedmann, a philosopher-humanist, enjoys a considerable reputation in Italy as a founding father of the ethnography of Italian peasantry, but has remained less known in America. In his correspondence with Redfield, Friedmann emerges as a prototype of an interdisciplinary researcher. Indeed, the correspondence suggests that Redfield was thinking of Friedmann when, in his remarks at Swarthmore,4 he called for a broader approach to the study of villages that would draw on historical, philosophical, and other kinds of research. Appearing here for the first time in print, the correspondence allows the reader to follow the growth of the relationship between the two men from their initial programatic agreement on the need for cooperation between their respective fields to the refinement of new terms and concepts. Displaying by turns warmth and wit, discussion of complex ideas, and frank criticism, the letters bear the stamp of two individuals united by their common interest in peasantry and its world views, their common humanism, and by their relish for the English language.

The second main component of the volume consists of a group correspondence-discussion on peasantry that Friedmann organized and guided between 1954 and 1957 in order to extend his own discussions with Redfield to include students of peasantry around the world from diverse professions. Redfield supported the idea of this Symposium by correspondence and offered his first, Chicago lecture on the Peasants View of the Good Life for criticism as a way of getting the discussion going. The Symposium, or Friedmanns Irregulars, as Redfield affectionately called it, served as an interdisciplinary testing ground for ideas on the study of peasantry and provided a source of inspiration and material for the last part of Redfields 1956 book,