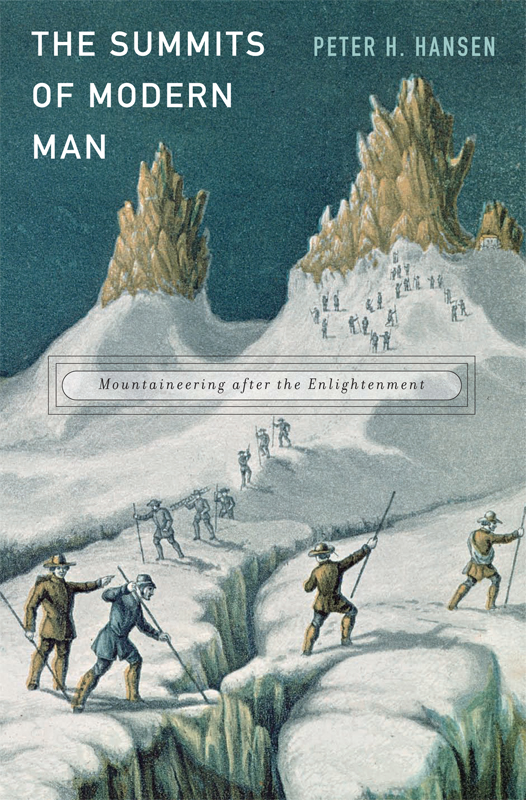

The Summits of Modern Man

PETER H. HANSEN

The Summits of Modern Man

MOUNTAINEERING AFTER THE ENLIGHTENMENT

HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England

2013

Copyright 2013 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

Jacket art: Departure from the Great Mulets: The Arrival at the Summit: The Ascent of Mont Blanc by Albert Smith, engraved by George Baxter, 1855 (color litho) after J. J. MacGregor. Private collection/Flammarion/ The Bridgeman Art Library

Author photo: Worcester Polytechnic Institute

Jacket design: Jill Breitbarth

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Hansen, Peter H.

The summits of modern man : mountaineering after the enlightenment / Peter H. Hansen.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-674-04799-0 (alk. paper)

1. MountaineeringHistory. 2. MountaineeringPhilosophy. I. Title.

GV199.89.H36 2013

796.522dc23 2012040365

For Allison

Contents

Illustrations

FIGURES

MAPS

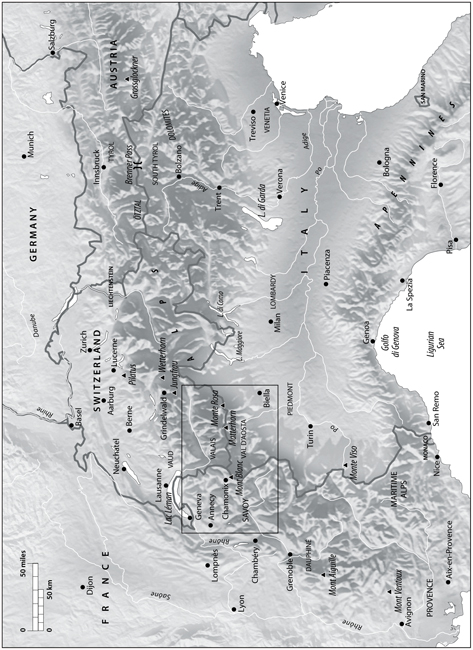

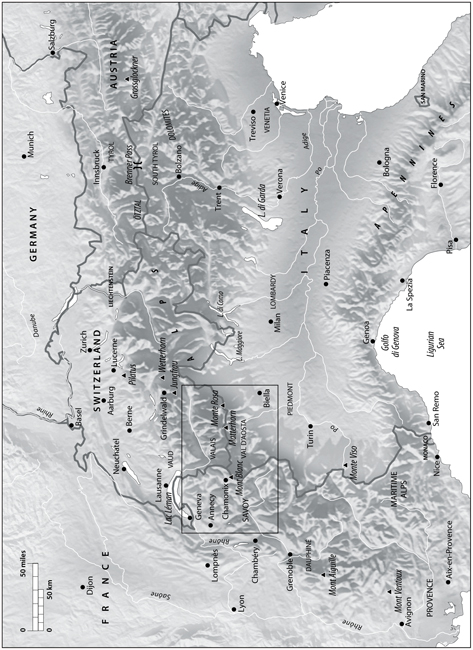

Map 1 The Alps.

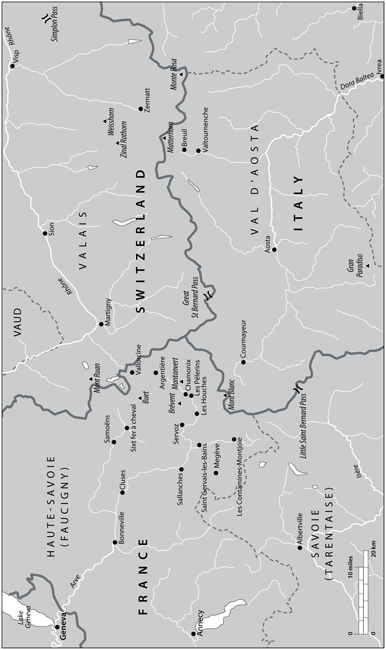

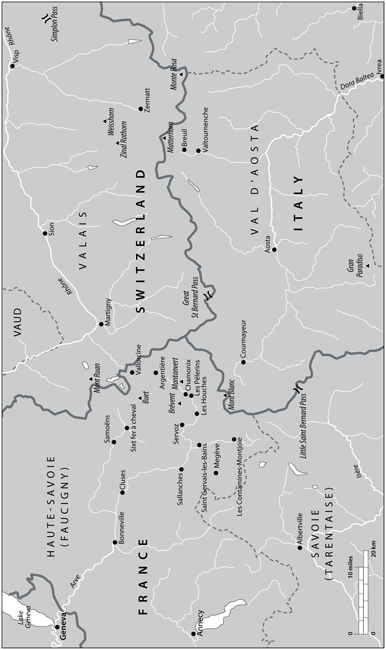

Map 2 Mont Blanc and the Western Alps.

CHAPTER ONE

ON BELAY

On belay! calls a climber after tying to the rope. Belay on! replies a partner, who secures the rope while the lead climber ascends. On belay signals that two people have arrived at a threshold. From that moment on, they are no longer autonomous but mutually interdependent. The rope binds them together. Neither occupies a position of superiority. Before proceeding, they acknowledge this partnership with another call and response: Climbing! Climb on!

Belay signals were standardized by the military in the mid-twentieth century. In the late eighteenth century, climbers tied together during mountain journeys were compared to groups of convicts. In the 1850s, ropes were used on glaciers, but some guides disparaged the rope as a sign of timidity and over caution.

By telling the history of discovery and first ascents of Mont Ventoux, Mont Aiguille, Mont Blanc, the Matterhorn, and Mount Everest, this book seeks to explain a particular strand of modernity in which modern man stands alone on the summit, autonomous from other men and dominant over nature. This modern man envisions the summit as an exclusionary space that may be occupied in succession, but not simultaneously. On this summit, even climbers tied to the same rope must race each other to the top. When and why did such feverish races for unaccompanied achievement, even if fictitious, become such a prominent and defining feature of modernity? During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, a diverse group of miners, surveyors, natural historians, and travelers collectively discovered the glaciers and mountains of the Alps in vertiginous corners of provincial Europe. Contemporary political debates over the extension of the right to vote in Geneva and the emancipation from feudal dues in Savoy placed men from these communities in competition with one another on an upward trajectory. In the 1780s, multiple people claimed the discovery or conquest of Mont Blanc, which resulted in debates over who was first. Such debates continued long after the French Revolution and the deaths of these climbers by the 1830s. In the mid-nineteenth century, wider groups of people made first ascents of the Matterhorn and other peaks in the Alps. Their achievements served as the model for recalling Francesco Petrarch on Mont Ventoux as the first modern man. Disputes over who was first on Mont Blanc, Mount Everest, and other peaks continued to entangle visions of sovereignty, masculinity, and modernity throughout the twentieth century.

The narratives of modern man imagine that an autonomous individual is first on a hitherto untrodden peak. Yet this modern man on the summit was almost never alone. For many mountaineers and historians, however, the assertion of individual will is the essence of mountaineering and modern man. The will to be first is said to distinguish modern men and women from premodern or nonmodern people who cower in front of mountains. But was premodern man never first anywhere? Could nonmodern man ever be alone in nature? Taken literally, the answer to such questions would be yes, of course. Yet such questions are badly posed and cannot be taken literally, for they are unimaginable without the peculiar emphasis on chronological priority and individual autonomy characteristic of this European modernity. The myth of modern man (or, more precisely, modern Western man) is that he is alone and thereby can be first. Yet the individual climber has never been as sovereign in practice as the mythology of modernity implies. Histories of discovery or mountaineering are usually told as if they follow an ineluctable and inexorable process of enlightenment, disenchantment, secularization, rationalization, and self-assertion when such categories are themselves modern forms of mythmaking.

Verbal signals at the threshold of a belay would be misunderstood if viewed solely as examples of military standardization. In fundamental respects, belay commands belie, if only temporarily, assumptions of individual autonomy. Climbers on belay declare a covenant: we are more entangled and attached than in everyday life and we acknowledge this interdependence for the duration of the belay. It would be inaccurate to say climbers never care who is first when, historically, they clearly did for many years and, some might say, still do. Climbers on the same rope are still asked, Who was first? because the question envisages not mutual interdependence but an unencumbered self. Mountain climbing did not emerge as the expression of a preexisting condition known as modernity, but rather was one of the practices that constructed and redefined multiple modernities during debates over who was first.

PLAYGROUND OF EUROPE

The rope should be invariably worn on all difficult ice or rock slopes where a fall is possible, advised Leslie Stephen in The Playground of Europe (1871). Stephen was a London literary critic and author, as well as a former Cambridge tutor, future editor of the Dictionary of National Biography , and the father of Virginia Woolf. The frontispiece of his book depicts a scene during the 1864 first ascent of the Zinal Rothorn, a peak with a knife-edged crest between the Matterhorn and Weisshorn near Zermatt, Switzerland. Stephen scrambles up the crest with his back to the viewer as the rope is held taut from above, and he steps on the shoulders of another climber braced against the rock (

This solidarity did not always extend beyond the duration of the climb or the length of the rope. Stephen repudiated the view that he should be considered the hero of his Alpine adventures and attributed all his success to guides, whose feats were made more difficult by taking with him his knapsack and his employer. His favorite Swiss guide, Melchior Anderegg, became a family friend, yet Stephen remained keenly aware that their views of mountains and modernity diverged. Stephen opened the Playground of Europe by describing a train ride through London with Anderegg. Looking at a dreary expanse of chimney-pots on the edge of this dingy metropolis, Stephen remarked with a sigh, That is not so fine a view as we have seen together from the top of Mont Blanc. Ah, sir! was [Andereggs] pathetic reply, it is far finer! Was his guide a fool or were his own beliefs folly? Neither, Stephen argued, since a similar shock awaited anyone who read Alpine literature from previous centuries.