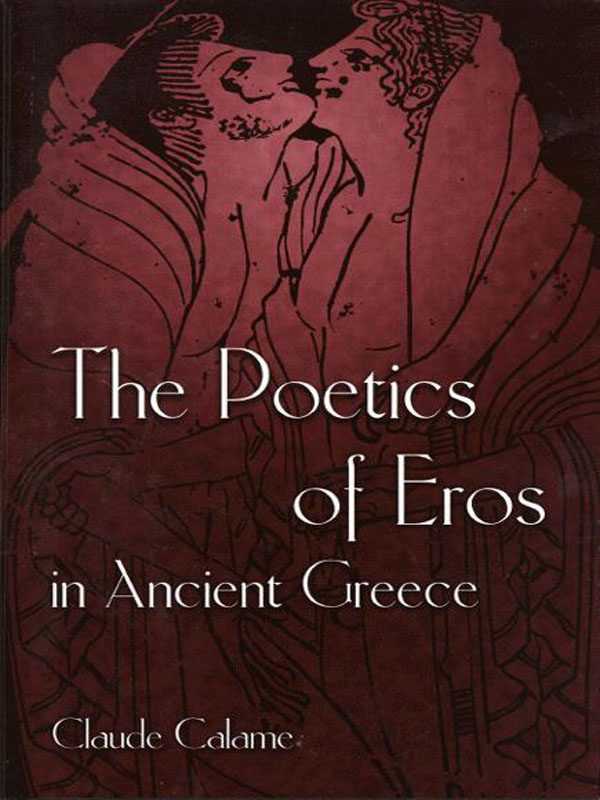

THE POETICS OF

EROS IN ANCIENT GREECE

THE POETICS OF

EROS IN ANCIENT GREECE

CLAUDE CALAME

Translated by Janet Lloyd

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY

Originally published as I Greci el leros: Simboli, pratiche e luoghi

Copyright 1992 Gius. Laterza & Figli Spa, Roma-Bari

English translation copyright 1999 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, Chichester, West Sussex

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Calame, Claude.

[Greci e leros. English]

The poetics of eros in Ancient Greece / Claude Calame ; translated

by Janet Lloyd.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-691-04341-8 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Erotic poetry, GreekHistory and criticism. 2. Literature and societyGreece. 3. Sex in literature. I. Lloyd, Janet.

II. Title.

PA3111.C35 1999 881.01093538dc21 98-37129 CIP

This book has been composed in Sabon

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper)

http://pup.princeton.edu

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Have you not yet noticed that pleasure, which is certainly the sole motive for union between the two sexes, is nevertheless not enough to form a bond between them?

Father Choderlos de Laclos, Les Liaisons dangeureuses, Paris, 1782 (Letter CXXXI, from the Marquise de Merteuil to the Vicomte de Valmont)

.

So we see Love chosen as king, chief magistrate, and harmonizer.

Plutarch, Amatorius, 763e, quoting Hesiod, Plato, and Solon

CONTENTS

TRAGIC PRELUDE

The Yoke of Eros 3

CHAPTER I

The Eros of the Melic Poets 13

CHAPTER II

The Eros of Epic Poetry 39

CHAPTER III

The Pragmatic Effects of Love Poetry 51

CHAPTER IV

The Pragmatics of Erotic Iconography 65

PART THREE: EROS IN SOCIAL INSTITUTIONS 89

CHAPTER V

Eros in the Masculine: The polis 91

CHAPTER VI

Eros in the Feminine: The Oikos 110

CHAPTER VII

Dionysiac Challenges to Love 130

CHAPTER VIII

The Meadows and Gardens of Legend 153

CHAPTER IX

The Meadows and Gardens of the Poets 165

CHAPTER X

Eros as Demiurge and Philosopher 177

CHAPTER XI

Mystic Eros 192

ELEGIAC CODA

Eros the Educator 198

ILLUSTRATIONS

PHOTOGRAPHIC CREDITS

: Staatliche Museen, Berlin (phot. Jutta Tietz-Glagow).

: British Museum, London.

: The Art Museum, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey.

: Muse du Louvre, Paris.

: Museo Nazionale di Villa Giulia, Rome.

FOREWORD

Froma I. Zeitlin

I N RECENT YEARS, one of the most fruitful areas of inquiry into the life, thought, and culture of ancient Greece has been the study of that elusive figure-concept called Eros and the specific nature and extent of erotic experience. The Greeks themselves divinized carnal desire in the figure of Eros, attesting to the enduring power of this most essential of human instincts. For them, Eros, as configured in literature and art, in myth as in cult, in drama as in philosophy, is claimed to be universal, holding sway over all of nature, and to have irresistible appeal, even to the gods themselves. In most versions, he is the child of the goddess Aphrodite; in others, he arises with the first stirrings of creation; while in the famous, but idiosyncratic, myth attributed to Socrates in Platos Symposium, he is the child of Poros (Resources) and Penia (Poverty), by nature neither mortal nor immortal but always oscillating between a condition of plenitude (life) and loss (death). From the archaic period through the classical and Hellenistic ages and down to the end of antiquity, the Greeks never ceased their explorations into the physiology and psychology of desire. Recording endless and varying encounters with the power of Eros through storytelling, dramatic enactments, personal lyrics, visual imagery, and theoretical speculation, they also transmitted to the Western imagination the powerful idea that their version of a universal Eros was indeed universal.

In our contemporary climate of research, however, where mystery has yielded to demystification, universals have given way to historical specificities, and the claims of nature are ascribed rather to notions of cultural constructs, social institutions, and discursive practices that change and diversify over time, the investigation of Eros has taken a different turn. We look now to Eros as a historically and culturally conditioned set of rules, ideas, images, fantasies, norms, and practices. The emphasis falls on difference rather than on perceived affinities or continuity of influence. The Greeks are not us, they are other; and Eros, above all, can serve as the ultimate proof of the conviction that every culture determines its own variety of meanings for nature, its own shifting representations of the human body, its own perceptions of sex and gender, and above all, its own historical psychology and social expectations.

In this enterprise, Claude Calames expertise is indisputable. In his two-volume study of choruses of girls in archaic Greece (Les choeursde jeunes filles en Grce archaque), published a little more than twenty years ago (1977) and now available in English translation (1997), Calame produced a pioneering work in myth, cult, poetics, and social practices, which for the first time demonstrated the significance of feminine initiations into adulthood and revealed the fundamental significance of Eros in the acculturation of the young. This work became indispensable reading. He continued to take the lead in the field, both in a volume he edited in Italian, LAmore in Grecia (1983, 4th ed. 1988), which further defined the parameters of inquiry, and even more, in numerous essays of his own which pertain in whole or in part to questions of ancient Greek sexual attitudes and concepts.

While a great deal of work has been produced on these topics in recent years, including the last two volumes of Foucaults investigation of the history of sexuality, Calames contribution to the subject of Eros in this small but authoritative book represents the sum of his thinking over a number of years. The voice is distinctive and it is magisterial. It bears the hallmarks of his unusual combination of skills that joins philological acumen with an anthropological point of view. The erudition is prodigious, in full control of primary sources, secondary literature, and theoretical issues. Yet in its selection and organization of a vast amount of disparate material into a lucid but complex whole, the book is easily accessible to any reader, both the specialist and nonspecialist, at whatever level of guidance and information is desired.

Calame begins rightly with a semantic study of Eros as well as its mythic and cultural framework before setting out to look more historically at the differences between archaic and classical Greece, with strong attention to differences of modes of expression and their respective social venues. Calame persuasively argues that Eros is first of all rooted in the literary and pictorial genres, which give a variety of expression to concepts of Eros, which in his view are the inventions of poets and painters that left an enduring mark on future developments. Eros, as he puts it, is both a divine figure and a physiology of desire, with certain symptoms and certain modes of action which operate in a network of social relations. Poetry (and its performance on dictated occasions) was itself an institution in its own right and played a major role in Greek civic life. Thus, starting from poetry and iconography and their symbolic values, Calame marks his intention to specify a history of Eros that is dependent on its institutional rolesin ritual celebrations, in educational practices of an initiatory type, in a variety of social settings, in the Dionysiac theater of tragedy and comedy, as well as in real and imagined topographies of space (e.g., meadows, mountains, and gardens)to conclude finally with an attestation of the central significance of the power of Eros in cosmology, philosophy, and mystic speculations.

Next page