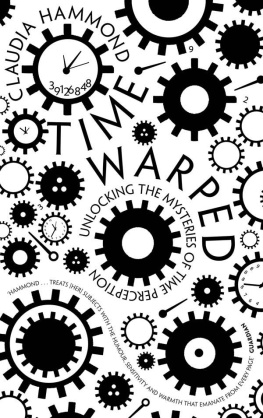

Also by Claudia Hammond

Emotional Rollercoaster:

A Journey through the Science of Feelings

Published in Great Britain in 2012 by Canongate Books Ltd,

14 High Street, Edinburgh EH1 1TE

www.canongate.tv

Copyright Claudia Hammond, 2012

The moral right of the author has been asserted

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 84767 790 7

eISBN 978 0 85786 345 4

Typeset in Plantin Light by Palimpsest Book Production Ltd, Falkirk, Stirlingshire

This digital edition first published in 2012 by Canongate Books

For Tim

The only reason for time is so that everything doesnt happen at once.

Albert Einstein

INTRODUCTION

WHEN CHUCK BERRY finds himself at the edge of a cliff or at the top of a mountain, he likes to jump off. When hes in a plane, he likes to jump out. This is not Chuck Berry the famous rock-and-roll singer, I hasten to add, but Chuck Berry the Kiwi king of skydiving and base-jumping. You may well have seen him in adverts for fizzy drinks. For Lilt, he jumped out of a helicopter while riding a bicycle twice. Now hes sponsored by Red Bull, but you can be sure that he experiences more than a caffeine rush as he falls through the air with a parachute, choosing not to open it until the last possible moment.

For 25 years Chuck Berry has practised plummeting through the sky, whether skydiving, hang-gliding, microlight-flying or parachuting (once he even used a customised tent as a canopy); but his speciality is base-jumping. One of the more extreme extreme sports, it takes its name from the four categories of fixed objects from which you can jump buildings, antennae, spans (bridges) and the earth (in practice, a cliff). Since 1981 there have been at least 136 fatalities; it is a sport so dangerous that one in 60 participants is expected to die doing it.

For Chuck, the key to survival resides in his ability to control his mind. Before he leaps, he visualises the exact steps he will take to achieve a successful outcome. So while any of the rest of us who found ourselves teetering on the top of the worlds tallest building (the K.L. Tower in Kuala Lumpur) would be likely to picture all the things that could go wrong getting blown into another building, opening the parachute too late, ending up a bloody mess on the street 1,381 feet below Chuck carefully calculates the wind direction, decides on the optimal point to open his chute and pictures himself floating down to make the perfect landing on the selected spot. Of course it helps that he also does months of planning.

With so many years experience, a Swift flight that Chuck took one New Years Day should have been easy. A Swift is a cross between a plane and a hang-glider and is said to combine the glorious soaring abilities of a glider with the convenience of being able to ascend into the air by simply running off the side of a mountain no need for a plane to tow you up into the sky. Whats more it folds up small enough to fit on top of a roof rack. The front half looks like an elegant paper plane with extra-long, aerodynamic wings, while the body of plane is very short and the tail is missing altogether. Theres a little cockpit for the pilot, which covers only your head, shoulders and arms, and your legs hang out of the bottom to allow you to run down the hill. Picture Fred Flintstone running along the ground to start his Stone Age car and then disappearing over the edge of the cliff and taking flight.

For his flight in the Swift, Chuck chose Coronet Peak just outside New Zealands bungee-jumping capital, Queenstown. It was a beautiful summers day and the mountain was outlined against the deep blue sky like a theatre scenery flat. It should have been the perfect location, but for Chuck the idea of some gentle soaring in this awesome immensity was a little tame. Some aerial acrobatics would sharpen the thrill. So, riding a thermal, he took the hybrid glider up to a height of 5,500 feet and then plunged her into a steep nosedive. The plan was to cut the dive at the last possible moment and then bank up towards the heavens again. No problem, right?

Wrong. The whole glider started shaking and bucking violently, and, as a former aircraft engineer, Chuck knew exactly what was happening. This was what was known in the trade as flutter a term devised by someone big on understatement when the wings of an aircraft twist up and down repeatedly until eventually they flap themselves to death.

Within moments, both wings had sheared off completely and Chuck found himself in freefall. Speeding towards the ground was usually his idea of fun. But this time there was nothing to slow his descent, nothing to break his fall, nothing to save him hitting the ground at breakneck speed. Even so, as he hurtled to earth his GPS tracker would later show rescuers that he had fallen at a speed of 200km an hour Chucks mind was capable of detailed, rational thought.

Although he was now hanging outside the cockpit of a glider without wings, looking up, he saw that he was still attached to much of the wreckage. His mind went into overdrive. He remembers exactly what he was thinking:

There had to be a way to get back into the remains of the glider. Why couldnt he climb up into the cockpit? There had to be a way. Cant I pull myself up? Surely. What would James Bond do? Come on, dude, do something! I have to do something. Dont look at the ground. Its too close. Theres no time. But there has to be a way. It must have been flutter. The lever! The lever for the emergency chute. If I can just get to the lever. It should be there! Surely it has to be there. How long have I been falling for? This is taking ages. There are the hills. Not much time left. Too windy to think. This is the most important decision Ill ever make. Do something! Save yourself! Get to that lever and pull!

Now, bear in mind that this interior dialogue, all of these thought processes, all of this precise mental calculation, would later be revealed by Chucks GPS system to have taken place within a matter of seconds. But for Chuck it felt like a lot longer. He knew that he had to act fast, but he had enough time plenty it seemed to think and to take action. For the observer, the seconds flashed by. For Chuck, it seemed to extend almost endlessly. The same time-frame with two very different perceptions of time passing. His New Years Day glimpse of eternity is a perfect, if extreme, example of this books central theme: the subjectivity of the experience of time. In situations like the one he faced, time is weirdly elastic.

We have all experienced moments in life where time becomes warped. When we are in fear of our lives, like Chuck, it seems to slow down. When we are enjoying ourselves, time flies. As the years go by, life feels as though its speeding up. Christmas comes round that bit faster every year. Yet when we were children, the school holidays seemed to stretch on for months.

In this book Ill be asking whether this stretching and shrinking of time is simply an illusion or whether the mind processes time differently at different moments of our lives. Time perception the way we subjectively experience time, what time feels like to us as individuals is an endlessly fascinating topic because time constantly surprises us; we never quite get used to the way it plays tricks on us. A good holiday races by; no sooner have you settled in than its time to think about packing to leave. Yet the moment you arrive home, it feels as though you have been away ages. How is it possible to have such contradictory experiences of the same holiday?

Next page