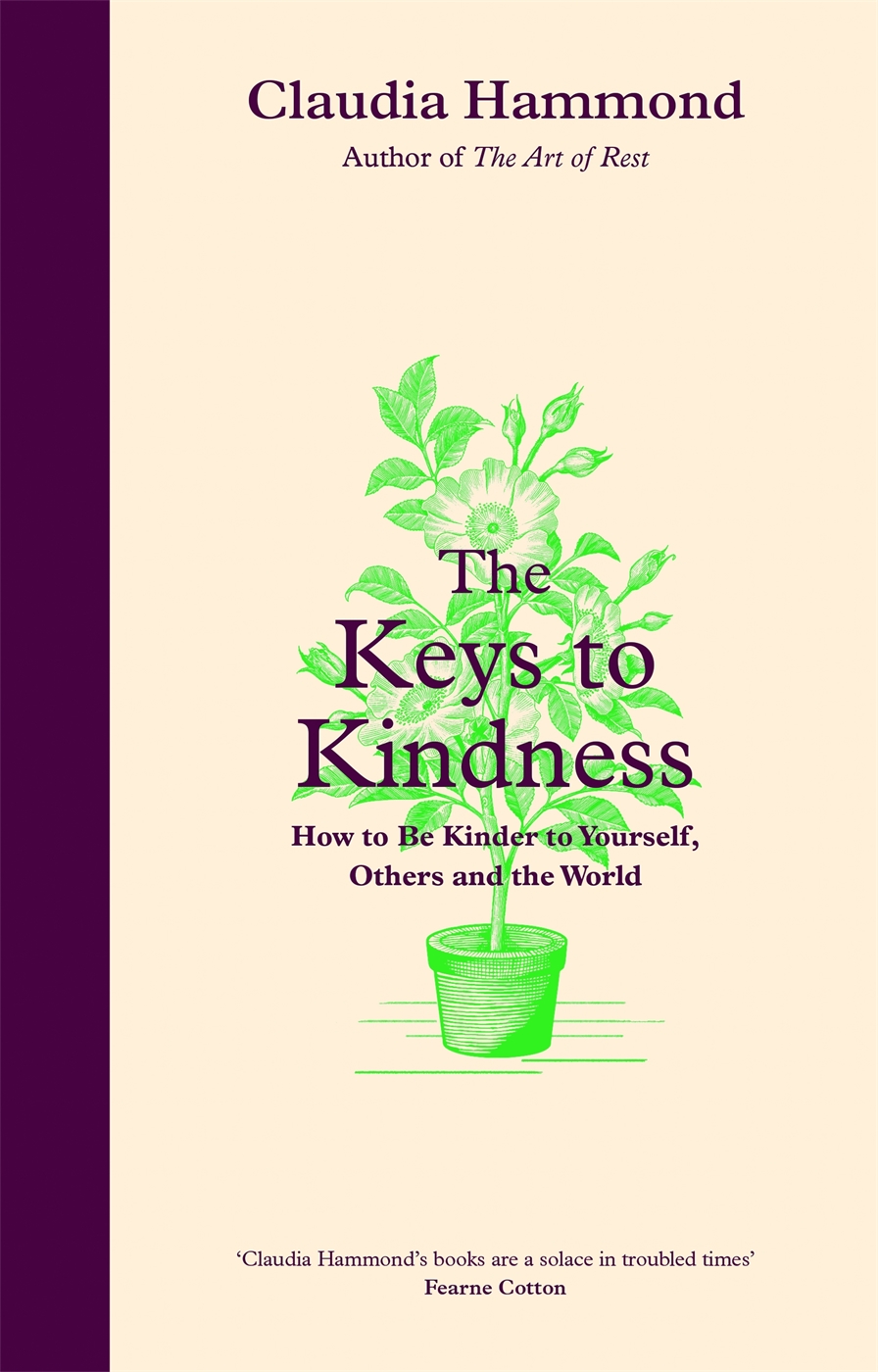

Also by Claudia Hammond

Emotional Rollercoaster: A Journey Through the Science of Feelings

Time Warped: Unlocking the Mysteries of Time Perception

Mind Over Money: The Psychology of Money and How to Use it Better

The Art of Rest: How to Find Respite in the Modern Age

First published in Great Britain, the USA and Canada in 2022 by Canongate Books Ltd, 14 High Street, Edinburgh EH1 1TE

Distributed in the USA by Publishers Group West and in Canada by Publishers Group Canada

canongate.co.uk

This digital edition first published in 2022 by Canongate Books

Copyright Claudia Hammond, 2022

The right of Claudia Hammond to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Extract from To Kill A Mockingbird by Harper Lee. Copyright Harper Lee, 1960. First published in Great Britain by William Heinemann 1960, Arrow Books, 1989, 2010. Reproduced by Permission of The Random House Group Limited

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on

request from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 83885 444 7

Export ISBN 978 1 83885 445 4

eISBN 978 1 83885 446 1

To Fiona, who is always kind

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

I used to live not far from Abbey Road in London. When occasionally I drove along it, I was always super alert as I approached a certain zebra crossing. This crossing was immediately outside the famous Abbey Road Studios where the Beatles recorded most of their iconic albums, including of course, in 1969, Abbey Road. The reason for my caution was that there was invariably a group of tourists on the crossing one of them barefooted, none of them paying heed to the traffic who were intent on reproducing the shot of John, Ringo, Paul and George from the album cover, while a friend or passer-by took a photo of their homage to the Fab Four.

The Beatles are of course among the most famous people who have ever lived feted and adored by millions. But the grand monument, in the middle of a junction close to the zebra crossing, has not been erected to honour their achievements. This monument is perhaps 18 feet tall and built of grey stone. On one of its plinths, there is a bronze sculpture of a muse playing the harp. On the other, there is a copper roundel depicting a distinguished, bearded face of a man in noble profile. Two grand lamp standards stand guard on either side of the monument. Who could warrant such a lavish memorial? And why was it erected?

The monument is to a Victorian sculptor called Edward Onslow Ford. So thats the who part. But Ive always found the why part particularly heartwarming. Because the reason Onslow Fords memory was marked in so striking a way was that he was so popular with his students and other sculptors for his charming disposition that they raised a considerable sum to build this large memorial to him after his death in 1901. Letters of condolence to his widow in his archive housed at the Henry Moore Foundation speak of his great kindness. The inscription on the memorial reads: Erected by his friends and admirers. To thine own self be true.

There are, I think, important lessons from the story of Onslow Ford, who it seems did succeed in being true to himself. First, it shows that we do value kindness to some extent enough in exceptional cases to erect monuments to people who personify it. But second, it shows we perhaps dont value it enough. Compared with the Beatles, Onslow Fords lasting impact on our culture is fairly minimal, so despite his memorial, my guess is that soon he will be pretty much forgotten, while the Beatles will surely be remembered for decades (even centuries?) to come. Genius and achievement are rightly revered. Im not for a moment suggesting we should devalue these attributes. But I am suggesting that we should, like Onslow Fords friends, notice and treasure the humbler virtue of kindness more than we sometimes do.

To this end, The Keys to Kindness makes the argument for taking kindness more seriously and valuing it more deeply. We are kinder than we might think, but we could be kinder still with enormous benefits for our personal mental health and well-being, as well as for society, the economy and the environment. Using the latest psychological evidence from around the world, and drawing on a new and unique study, I will demonstrate that kindness helps not just others, but us too.

Being kind is not always easy though. The way the world is currently constructed can lead us to be tough on ourselves and on others. Schools, universities and workplaces are in some ways kinder places than they once were. Gone are the days when it was OK to throw a typewriter at someone (when I was new to a radio newsroom, older colleagues would tell me tales of such events). Gone are the days when children were caned for failing to remember their times tables. But across society, a premium is still put on personal achievement and individual success, often at the expense of others and sometimes through developing a hard and ruthless streak in ourselves. The idea can still get into us that to be kind is to be weak and that weakness means you lose out. I will be challenging that notion, backed up by extensive evidence that we all benefit from greater cooperation and compassion, and that being kind and empathic certainly isnt an impediment to success or even acclaim. More than that, the more kindness there is, the more the world will benefit.

I will also look into the tricky question of how to define what kindness is.

For instance, I wonder how many of these statements relate to you?

I think its right to give everyone a chance

I find it easy to forgive

I share things I would rather keep for myself

I have surprised another person with an act of kindness

I smile at strangers

Ive done something that upset me to help a friend

Dont worry if you dont identify with all of these statements. They represent some of the different types of kindness, so you may be more inclined towards tolerance or empathy, but less inclined towards taking deliberate actions to be kind or avoiding acts which might be unkind. Most likely, you have acted in all these ways on some occasions, but not on others. You are probably a kind person, but not all the time and you show your kindness in different ways at different times.

Kindness, you see, is not simple. Nor is it just one thing. It is multifaceted, hard to pin down and often misunderstood. I once offended the widower of a brilliant researcher by telling him that despite only having met his wife on a few short occasions I could tell what a really kind person she was. I meant it as a true compliment, but he felt the praise was rather bland and patronising, downplaying his wifes professional achievements. His reaction was perhaps understandable, particularly given the routine devaluation of womens accomplishments in traditionally male arenas. But even so, it was a shame an instance of the attribute of kindness being under-appreciated in our culture. Id like to live in a world where the greatest thing you could say about a person is that they were kind.

Seven Keys to Kindness

In this book, I explore seven keys to kindness, some of which may seem obvious to you, others less so. No one key is more important than any other; instead they fit together to provide a full picture of all aspects of kindness which we need to consider in order to make the world a kinder place.