THE FATAL STRAIN

On The Trail of Avian Flu and the Coming Pandemic

In an underground bunker carved from the soft Swiss hills above Lake Geneva, the daily intelligence briefing they call the morning prayers was beginning. The intel officers had been up since dawn, sifting through reams of electronic communications for any hint of an emerging threat, any anomaly portending disaster. Their customized computer search engine had culled and translated news reports, Web postings, and online rumors in six different languages, and now these were stitched together with official bulletins and tips from informants into a tapestry of microbial peril. Like the Men in Black who work to keep humanity blithely ignorant of the menace to this planet, these officers were engaged in a perpetual, often unpublicized contest with the most accomplished killers known to man. But this was for real.

The officers filed into the command center, a converted movie theater two floors beneath the global headquarters of the World Health Organization (WHO). They passed through doors secured with electronic locks that limit access to all but the privileged few and pulled up black chairs around the blond wood table. There was space for only six. So nearly twenty othersincluding special operations staff, disease specialists, and a few of the agencys senior brasslined the edge of the room, some seated, others forced to stand. The chief of the intel section was a stylishly dressed Australian woman, a former senior disease investigator in Canberra who had been seconded to WHO in response to the 2001 anthrax attacks in the United States. She convened the briefing, moving briskly down the list of newly uncovered outbreaks. Some were still unidentified. There were reports and rumblings from Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and the Caribbean. A pair of large plasma screens on the wall flashed maps of these evolving hot spots. A red digital display scrolled through the time in eighteen major cities from Geneva and Washington to Delhi, Hanoi, and Jakarta.

The room was small, even cozy, with recessed lighting and gray carpeting. This was the mezzanine that once housed the movie theaters projector. But if any of the threats developed into a true epidemic, the full war room below, called the Strategic Health Operations Center, would be activated. More commonly known as the SHOC, it offers dedicated satellite communications linking it to 150 agency offices and government ministries around the world. Dispatches from field investigators and doctors in distant hospitals can be beamed directly to the high-definition video wall at the front. A private network instantly transmits data from the remotest of outposts to a series of black planar monitors, which retract with a hum into the surface of the U-shaped table in the middle of the room. The center has its own dedicated power source and computer servers, its own telephone exchange, ventilation, and air-conditioning. In case of a pandemic or a biological weapons attack, the SHOC must go on.

The briefing this morning was confidential. The premature disclosure of a suspected outbreak could sabotage WHOs ability to mount an emergency response. It might cause panic, crippling economies and embarrassing governments.

But given a rare opportunity to sit in on morning prayers, I got a glimpse of humanitys existential conflict with the microbes. Ebola. Monkey pox. Cholera. Plague. Yet of all these and more, it was flu that my hosts feared most. Not ordinary flu, not the kind that sends the sick to bed each winter with chills and a fever, that keeps children home from school and nursing homes on alert. They were watching warily for a novel strain of flu, a new virus against which no one on Earth has natural immunity.

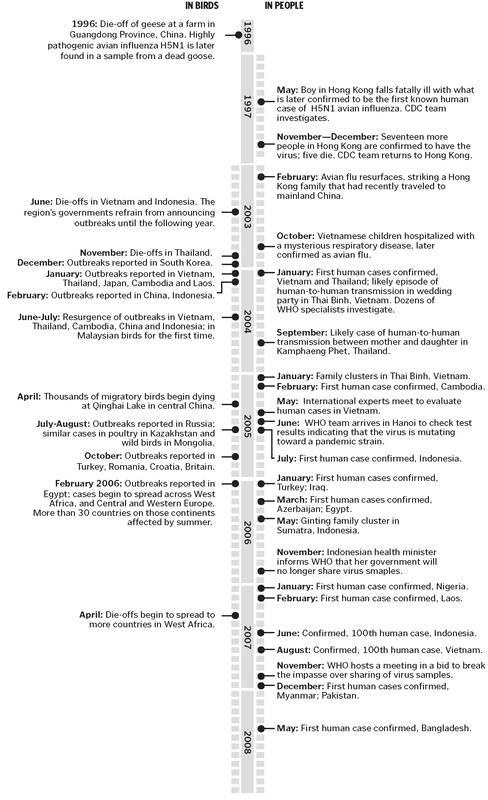

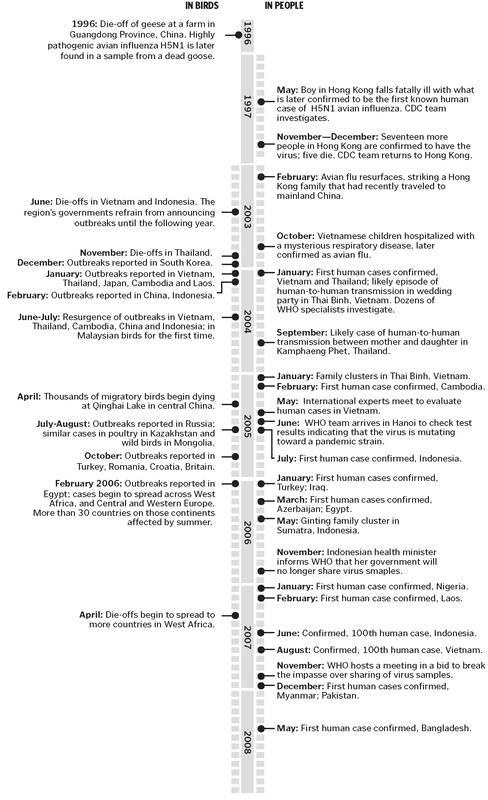

In recent years, such a strain has emerged with the deceptive name of bird flu. All flu viruses in fact emanate from birds. But this particular strain was supposed to stay there. Instead it confounded scientists by repeatedly leaping the species barrier from poultry to people, often with lethal results. Now the agencys officers were searching for any unusual outbreak signaling a sinister mutation in this fatal strain, any omen of a gathering pandemic. A few genetic tweaks and millions could perish.

As an Asia correspondent for the Washington Post covering the spread of bird flu, I had learned not to underestimate it. Still, I was surprised by what I saw that morning in the bunker. At the top of the agenda were two reported deaths from avian influenza on the eastern edge of Europe, a continent that had so far been spared human cases. I was required to not identify the specific country but can say that these fatal infections, if confirmed, would have opened a new frontier.

Ultimately, after investigation, the bulletin was dismissed as unsubstantiated. But I was struck by the urgency with which it was handled. The information had originated with Russian medical staff working near the site of the suspected outbreak. From there, the reports had reached U.S. intelligence, which was growing increasingly anxious about the prospect of a flu pandemic. Intelligence agencies worry about its potential to disrupt the world economy, stoke political unrest, and escalate tension among countries vying for scarce medicine and other essentials that would run short. From the U.S. Office of the Director of National Intelligence, the information found its way to WHO headquarters, which in turn directed its European regional office to investigate. Within two days the report was run to ground. The episode underscored for me how gravely the pandemic threat was viewed by those in the know, even as media coverage ebbed and flowed.

By the time I sat in on the briefing, flu specialists had long since concluded we were closer to a global epidemic than wed been in a generation. Even those who ran the command center, which integrates the best minds and technology the world can muster, conceded that they cannot prevent the inevitable. They didnt know when, and they didnt know whence. But the pandemic was coming.

* * *

Dr. Michael Ryan has hunted down some of the most virulent biological agents of modern times. He has parachuted into the worlds bleakest corners to confront the horrors of Ebola and lesser-known hemorrhagic diseases like Marburg fever, Crimean-Congo fever, and Rift Valley feverviruses so infectious, so devastating that doctors don biosafety space suits when they encounter these so-called special pathogens. As a member of WHOs special operations team, he has also helped stanch incipient epidemics of meningitis and cholera. Hes braved guerrilla insurgencies, minefields, and wars on three continents to reach these outbreaks, dodging drug runners in Afghanistan during the Taliban era and Somali bandits in Kenya. He has crossed battle lines in the Ugandan bush to secretly win the cooperation of the cruel, cultish rebels of the Lords Resistance Army. I was shaking in my boots, he recalled. He fractured his spine in multiple places when his car was forced off the road in Kurdistan by an Iraqi military convoy during the rule of Saddam Hussein and careered down an embankment. Yet each time, Ryans mission has succeeded. This has instilled in him an outsize sense of confidence. Until now.

Ryan is a burly, red-haired Irishman with lively hazel green eyes, full cheeks, and a gap-tooth smile. He grew up playing Gaelic football in what he describes as the wild and savage county of Mayo on Irelands west coast, and he still has the build. His colleagues have called him the bulldozer for the way he muscles aside bureaucratic and logistical obstacles. More often, they call him the Irish traffic cop. After 2001 he took charge of the urgent comings and goings of scores of WHO teams dispatched to the field each year. As the indomitable director of Alert and Response Operations, he assumed overall responsibility for intelligence activities and emergency assistance to stricken countries, as well as the divisions dealing with specific diseases, including special pathogens and influenza. He is quick-talking and can-do, at times barely able to contain his restless intensity. His impassioned monologues cascade from topic to topic. His beefy hands punctuate each exuberant thought. His full, red eyebrows bob, and his chair creaks beneath his shifting frame. Though some agency old-timers initially dismissed Ryan and his crew as a bunch of cowboys, he has brought speed and smarts to fighting disease at a time when disease spreads faster than ever.