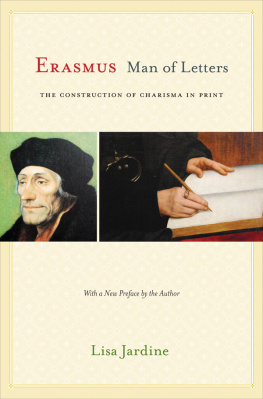

THE PRAISE OF FOLLY

THE PRAISE OF FOLLY

BY DESIDERIUS ERASMUS

Translated from the Latin, with an Essay & Commentary,

by Hoyt Hopewell Hudson

With an new foreword by Anthony Grafton

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 1941, 1969 by Princeton University Press

New foreword 2015 by Princeton University Press

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

First Princeton Paperback Edition, 1970

First Princeton Classics Edition, with a new foreword by

Anthony Grafton, 2015

Paperback ISBN: 978-0-691-16564-6

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015930404

Original cloth edition designed by P. J. Conkwright

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Contents

A PRELUDE TO THE PRAISE OF FOLLY: FOREWORD

TO THE PRINCETON CLASSICS EDITION |

A Prelude to The Praise of Folly

FOREWORD TO THE PRINCETON CLASSICS EDITION

T HE P RAISE OF F OLLY began as an elaborate joke, to be shared with a close friend. According to an old story, in 1499, when Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam first came to England, he met a brilliant young man at the table of the Lord Mayor of London. The two of them argued: cut followed thrust, learned joke capped learned joke. Finally, Erasmus said, Either you are More, or no one. Erasmus was right, and Thomas More, his dinner companion, replied, in the same spirit: You are either Erasmus, or the devil. In fact, Erasmus and More were properly introduced. But that was pretty much the only proper thing about their friendshipwhich grew, as the story suggests, from a shared sense of humor. In 1505, when Erasmus returned to England, they worked together on translations from Greek into Latin. Their author, Lucian, was a satiristlike them, a learned joker.

In 1509, as Erasmus rode back over the Alps from a triumphant tour of Italy, he decided that it would be fun to devote his learning and style to an ingenious paradox. He began to think about composing a paradoxa work in praise of folly. The connection to his friendship with More was evident from the start. Erasmus gave his text the Greek title M Eio (Morias Encomion)a praise of folly, but also a punning praise of More. Once he arrived in London, he found himself confined by ill health to Mores house. So he drafted the text. By the summer of 1510, he had finished the text and written a letter of dedication to More. It came out in 1511.

Erasmuss little book announced from the start that it belonged to an ancient genre of pedantic humor. Since antiquity, orators had practiced, as one of their standard exercises, the writing of speeches in praise of people, buildings, and cities. And since antiquity, satirists had made fun of these speeches by writing parodies of them. They pretended to praise, as Erasmus put it, Busirises, Phalarises, quartan fevers, flies, baldness, and pests of that sort [9]. In praising Folly, Erasmus made clear he worked within the classical tradition in literaturea point he went on to underline by casting his work in elaborate, demanding Latin and by stuffing it with allusions, not only to Lucian but also to other favorite writers, from the Roman poet (and satirist) Horace to Plato.

Yet the finished book was too long, too serious, and too challenging to be nothing more than an ingenious paradox. Erasmus not only invoked the conventions of ancient rhetoric; he then broke with them. Instead of writing in his own voice or creating the character of an orator to speak in his place, he portrayed Folly herself as speaking to an assembly of the learned, dressed in cap and bells and attended by servants named Philautia (self-love), Kolakia (flattery), Lethe (forgetfulness) and Misoponia (hatred of work). And instead of confining himself to gentle mockery, he produced a complex, puzzling and often-polemical discourse on contemporary society and religion.

The text starts without pyrotechnics. Folly claims credit for the existence of the human race, since that foolish, even silly, part, which cannot be named without laughter, is the propagator of the human race. When she goes on to point out that the pleasantest times of life are childhood and old age, and to argue that what men like best in women is their folly, she remains within the bounds of literary irony. But then she adds new colors to her self-portrait. Folly is not just the engine of procreation and the source of fun at banquets. She is the source of illusions. And only illusions make life possible. Folly tricks everyone into seeing nonexistent good qualities in themselves and others. Her magic enables husbands to tolerate wives, wives to tolerate husbands, and teachers to tolerate students. Without Folly, no one could bear his companions, to say nothing of himself: were you to bar me out, each man would be so incapable of getting along with any other that he would become a stench in his own nostrils, his possessions would be filthy rags, and he would be hateful to himself [28]. Human society, as Folly presents it, is not a cheerful array of old men and women playing with babies, but a hideous parade of the ugly and the infirm, the stupid and the cowardly, none of them able to see themselves, or one another, as they area procession scarier than that of the flagellants in Ingmar Bergmans The Seventh Seal. Only the delusions that Folly creates enable these monstrous creatures to make stable relationships with one another and to form a larger society.

Yet exposing these ugly truths is only the beginning of Follys project. Suddenly we find that she has stopped describing the shared follies of the human race and begun describing the various orders of society, starting with obsessive hunters and builders of new buildings, alchemists, and gamblers. The ironic encomium has become a different kind of text entirelyas Folly herself finally confesses, when she breaks off for fear I should seem to compose a satire rather than pronounce a eulogy [103]. And Folly has more important targets in view than wealthy sufferers from the Edifice Complex. Her satire takes in most social estates, but concentrates on powerful and problematic sets of clerics: theologians who confuse their obsessive concern with tiny distinctions between abstract concepts with the study of God; priests, bishops, and popes who mistake their titles and finery, their pursuit of titles and money, for the proper occupation of Christian priests; and monks who confound their maniacal efforts to follow pedantic, meaningless rules with true piety. Folly has turned on those who supposedly embody wisdom and piety, and exposed the hollowness of their claims.

Still, she is not done. In the third and shortest part of her speech, Folly pivots againthis time to the teachings of Christianity and philosophy. What looks to humans like wisdom, she argues, is really madnessas the prophets, Jesus and Paul all proclaimed, in passages that she deftly cites. True Christianity, Folly argues, yields none of the things that ordinary, prudent men and women seek: not wealth, not power, not fame. Instead, it offers the foolishness of the cross, by which Jesus brought healing to sinful humanity. Happily, Christianity is not the only subversive force at work, in a world that needs all the subversion it can get. True philosophy, she argues, is not a pursuit of useless knowledge or sophisticated logical tricks, but a study of death, in Platos words, because it leads the mind away from visible and bodily things, and certainly death does the same. True Christianity and true philosophy converge. Both teach those who embrace them to be fools to this world, rapt away in the contemplation of things unseen [120]. Existing schools and universities, popular theological schools and doctrines, which fail to teach these follies, are the pillars of a world that has turned itself upside down, mistaking death for life. By contrast, the experience of true religion is Moriae parsthe portion of Folly, [124] but also the portion of More, andaccording to a variant that appears in some editions of the textMariae pars, the portion of Mary, the lot of the contemplative sister of the busy Martha in the Gospel of Luke. Folly has taught a deeply serious lesson.

Next page