THE PROSTHETIC PEDAGOGY OF ART

Embodied Research and Practice

CHARLES R. GAROIAN

STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK PRESS

2013 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact

State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Production, Laurie D. Searl

Marketing, Fran Keneston

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Garoian, Charles R., 1943

The prosthetic pedagogy of art : embodied research and practice / Charles R. Garoian.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4384-4547-2 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. ArtStudy and teachingPhilosophy. 2. Art and society. I. Title.

N84.G37 2013

707dc23

2012010768

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

ILLUSTRATIONS

Cover photo: Tim Roda, Untitled #27, 2004, Silver Gelatin photograph on fiber matt paper, 22 28 (Courtesy Daniel Cooney Fine Art, New York, NY)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

It is with pleasure that I dedicate this book to Lilit Ayanian, who was born on May 31, 2011, during the final stages of my writing. Our first grandchild, she came into our lives in a year when so many of our close family and friends passed away, and in doing so, reminded us of the regeneration of life. What fascinates us about Lilit is her innocence, her inquisitiveness, and her limitless absorption of all things and happenings in her environment. Turning her head, twisting her body up and down, right and left, backward and forward, she hears and sees everything. She touches, holds, pulls, pushes, and taps all things within close proximity. Her learning is insatiable. Putting things into her mouth, she touches then tastes her world. Her wonderment at every movement and sound is infectious; it has effected an intensity and renewal in our lives, and confirmed the importance of what we do as parents and educators in the lives of our children.

I would like to thank the members of my family who embraced me with love and patience as I buried myself in the research process and the writing of this volume. Most specifically, Sherrie, who as my inspiration for the past forty-four years continually reawakens and reaffirms the importance of stepping outside of my academic frame of mind to see and experience the multiplicities and fullness that life has to offer. And, to Jason Garoian, and Stephanie and Garo Ayanian (Lilit's parents) who continue to inspire hope through their generosity, creativity, and loving hearts.

My research and writing of this book would not have been possible without the inspiration of my students and colleagues in the School of Visual Arts at Penn State University, and at universities across the United States and internationally. Their differing and peculiar ways of seeing and understanding has extended and expanded my scope of experiencing and valuing the world, and their boundless desire for making meaning through art research and practice continues to inspire my cultural work as a teacher, artist, and writer. Chris Staley, Yvonne Gaudelius, Dnal O'Donoghue, John Howell White, Christine Marm Thompson, Kimberly Powell, Graeme Sullivan, Gail Boldt, Jorge Lucero, Chris Schulte, Joe Julian, Kevin Slivka, Olivia Gude, Jerome Hausman, Liora Bresler, Rita Irwin, Laura Traf-Prats, B. Stephen Carpenter II, Elizabeth Garber, jan jagodzinski, James Hayward Rolling Jr., Stephanie Springgay are but a few who continue to foment my thinking about the educational significance of art research and practice.

Thank you to the following individuals and agencies who provided permission to publish the images that are contained within the pages of this book: artists Tim Roda, Brian Franklin, Stephanie Springgay, Nico Muhly, Francis Als, Dorothy Schultz, Louise Barry, Bryan Rogers, Rob Martin, Gene Cooper, Janine Antoni, and Chuck Close; art educators Montse Rif, Laura Traf-Prats, and Xavier Gimnez; archivist Heather Monahan at The Pace Gallery in New York City; Daniel Cooney Fine Art in New York City, Heather Monahan, Artists Rights Society, Art Resource, Visual Arts and Galleries Association, California Raisin Marketing Board, University of Pennsylvania Archives, Missouri Botanical Gardens, and Dr. Joseph (Joe) Julian Jr.

Finally, I am grateful for the encouragement and funding support that I received from Dr. Graeme Sullivan, Director of the School of Visual Arts, and Dr. Bill Doan, Associate Dean of Administration, Research, and Graduate Studies in the College of Arts and Architecture for the research and completion of this book project. And, I would like to acknowledge the support of Beth M. Bouloukos, Acquisitions Editor, and Laurie Searl, Senior Production Editor, at The State University of New York Press without whose advice and encouragement the publication of this book would not have been possible.

ONE

INTRODUCTION

The Prosthetic Space of Art

Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible.

Paul Klee, Schpferische Konfession

Gaps seem to give us somewhere to extend: space for our prosthetic devices.

Marilyn Strathern, Partial Connections

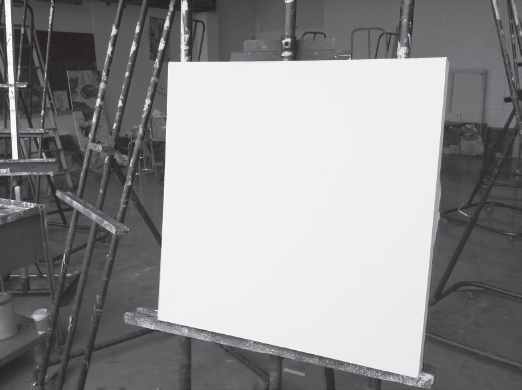

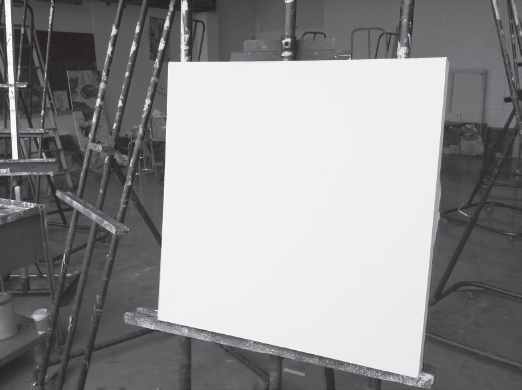

I have often wondered about that canvas (), that first canvas leaning against the wooden easel, the one that I stretched in the first, that beginning painting course in which I was enrolled years ago

its 18 24 dimensions

its pure, immaculate surface sealed with thick white gesso, reflecting bright light from an adjacent window, taut from drying and shrinking against the milled wooden bars upon which I had pulled and stapled its loose fabric

its unbleached cotton duck, which upon drying and shrinking, and stretching, resonated the thunder of a kettledrum in response to the thump of my snapping finger

its blank, empty space, suggesting a patch of skin from art history's body, loudly staring back daringly, returning my gaze

Figure 1.1. Stretched canvas, 2011 (Courtesy Charles Garoian).

that canvas, on easel and ready for painterly action

its space a lacuna, intimidating while inviting my leap into its open gap

the art classroom like that canvas, equally paradoxical, spatially available yet awesome and indifferent

Thanks to my unknowing teacher who invited my participation in the painting lesson, who enabled and encouraged me

to begin a process, a trajectory of work

to extend beyond

to reach outside the demarcated space, the bounded, rectilinear, pictorial edge of the surface while applying paint he said, his words suggesting the confidence of Francis of Assisi

to start by doing what's necessary; then do what's possible, and suddenly you are doing the impossible

to transgress the walls of the classroom

to disrupt its academic and institutional confines he said, by imagining, exploring, and creating in ways similar to the playful making, working, and living on the raisin vineyard and farm of my emigrant parents he said