Published by

Rupa Publications India Pvt. Ltd 2015

7/16, Ansari Road, Daryaganj

New Delhi 110002

Copyright Devdutt Pattanaik 2015

Illustrations Copyright Devdutt Pattanaik 2015

The views and opinions expressed in this book are the authors own and the facts are as reported by him/her which have been verified to the extent possible, and the publishers are not in any way liable for the same.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978-81-291-3770-8

First impression 2015

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Design and typeset in Garamond by Special Effects, Mumbai

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated, without the publishers prior consent, in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published.

To my friends Partho, who listens Paromita, who sees

Contents

Why My Gita

T he Bhagavad Gita, or The Gita as it is popularly known, is part of the epic Mahabharata.

The Bhagavad Gita

The epic describes the war between the Pandavas and the Kauravas on the battlefield of Kuru-kshetra. The Gita is the discourse given by Krishna to Arjuna just before the war is about to begin. Krishna is identified as God (bhagavan). His words contain the essence of Vedic wisdom, the keystone of Hinduism.

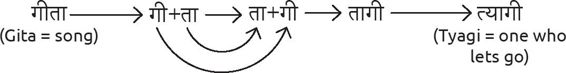

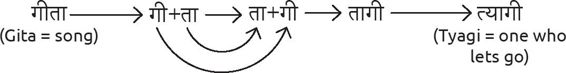

Ramkrishna Paramhansa, the nineteenth-century Bengali mystic, said that the essence of The Gita can be deciphered simply by reversing the syllables that constitute Gita. So Gita, or gi-ta, becomes ta-gi, or tyagi, which means 'one who lets go of possessions.'

Gi-ta to Ta-gi

Given that, it is ironical that I call this book My Gita.

I use the possessive pronoun for three reasons.

Reason 1: My Gita is thematic

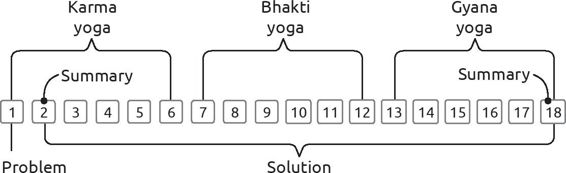

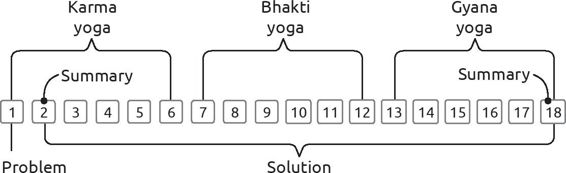

The Gita demonstrates many modern techniques of communication. First, Arjunas problem is presented (The solution itself is comprehensive, involving the behavioural (karma yoga), the emotional (bhakti yoga) and the intellectual (gyana yoga). However, no one reads The Gita as a book, or hears every verse in a single sitting.

Chapter Architecture in The Gita

Traditionally, a guru would only elaborate on a particular verse or a set of verses or a chapter of The Gita at a time. It is only in modern times, with a printed book in hand, that we want to read The Gita cover to cover, chapter by chapter, verse to verse, and hope to work our way through to a climax of resolutions in one go. When we attempt to do so, we are disappointed. For, unlike modern writing, The Gita is not linear: some ideas are scattered over several chapters, many ideas are constantly repeated, and still others presuppose knowledge of concepts found elsewhere, in earlier Vedic and Upanishadic texts. In fact, The Gita specifically refers to the Brahma sutras (brahmana and purusha are used for soul instead of atma. This can be rather disorienting to a casual reader, and open to multiple interpretations.

So My Gita departs from the traditional presentation of The Gitasequential verse-by-verse translations followed by commentary. Instead, My Gita is arranged thematically. The sequence of themes broadly follows the sequence in The Gita. Each theme is explained using several verses across multiple chapters. The verses are paraphrased, not translated or transliterated. These paraphrased verses make better sense when juxtaposed with Vedic, Upanishadic and Buddhist lore that preceded The Gita and stories from the Mahabharata, the Ramayana and the Puranas that followed it. Understanding deepens further when the Hindu worldview is contrasted with other worldviews and placed in a historical context.

For those seeking the standard literal and linear approach, there is a recommended reading list at the end of the book.

Reason 2: My Gita is subjective

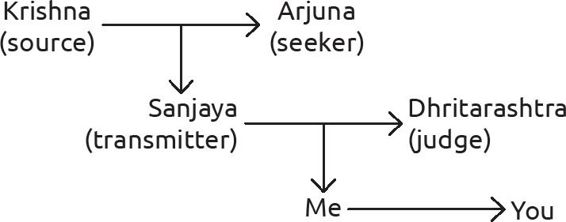

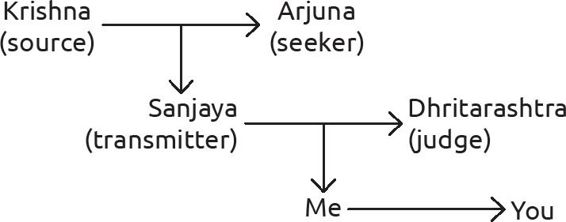

We never actually hear what Krishna told Arjuna. We simply overhear what Sanjaya transmitted faithfully to the blind king Dhritarashtra in the comforts of the palace, having witnessed all that occurred on the distant battlefield, thanks to his telepathic sight. The Gita we overhear is essentially that which is narrated by a man with no authority but infinite sight (Sanjaya) to a man with no sight but full authority (Dhritarashtra). This peculiar structure of the narrative draws attention to the vast gap between what is told (gyana) and what is heard (vi-gyana).

Krishna and Sanjaya may speak exactly the same words, but while Krishna knows what he is talking about, Sanjaya does not. Krishna is the source, while Sanjaya is merely a transmitter. Likewise, what Sanjaya hears is different from what Arjuna hears and what Dhritarashtra hears. Sanjaya hears the words, but does not bother with the meaning. Arjuna is a seeker and so he decodes what he hears to find a solution to his problem. Dhritarashtra is not interested in what Krishna has to say. While Arjuna asks many questions and clarifications, ensuring the discourse is a conversation, Dhritarashtra remains silent throughout. In fact, Dhritarashtra is fearful of Krishna who is fighting against his children, the Kauravas. So he judges Krishnas words, accepting what serves him, dismissing what does not.

Overhearing The Gita

I am not the source of The Gita. But I do not want to be merely its transmitter, like Sanjaya. I want to understand, like Arjuna, though I have no problem I want to solve, neither do I stand on the brink of any battle. But it has been said that the Vedic wisdom presented by Krishna is applicable to all contexts, not just Arjunas. So I have spent months hearing The Gita in the original Sanskrit to appreciate its musicality; reading multiple commentaries, retellings and translations; mapping the patterns that emerge from it with patterns found in Hindu mythology; and comparing and contrasting these patterns with those found in Buddhist, Greek and Abrahamic mythologies. This book contains my understanding of The Gita, my subjective truth: my Gita. You can approach this book as Arjuna, with curiosity, or as Dhritarashtra, with suspicion and judgement. What you take away will be your subjective truth: your Gita.

The quest for objective truth (what did Krishna actually say?) invariably results in vi-vaad, argument, where you try to prove that your truth is the truth and I try to prove that my truth is the truth. The quest for subjective truth (how does The Gita make sense to me?) results in sam-vaad, where you and I seek to appreciate each others viewpoints and expand our respective truths. It allows everyone to discover The Gita at his or her own pace, on his or her own terms, by listening to the various Gitas around them.

Next page