CONTENTS

The county of Argyllshire and the islands of Arran, Bute, and Lismore

The counties of Clackmannanshire, Dunbartonshire, Fife, Kinross-shire, Perthshire, and Stirlingshire

The counties of Dumfriesshire, Kirkcudbrightshire, and Wigtownshire

The counties of Ayrshire, Lanarkshire, and Renfrewshire

The counties of Berwickshire, East Lothian, Midlothian, Peeblesshire, Roxburghshire, Selkirkshire, and West Lothian

The counties of Aberdeenshire, Angus, Banffshire, Kincardineshire, Moray, and Nairnshire

The counties of Caithness and Sutherland

The counties of Inverness-shire and Ross & Cromarty

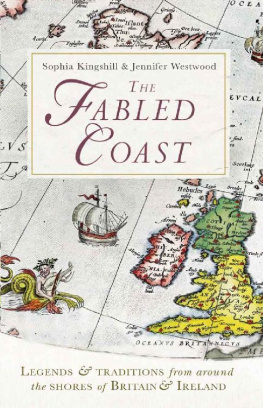

About the Book

Scotlands rich past and varied landscape have inspired an extraordinary array of legends and beliefs, and in The Lore of Scotland Jennifer Westwood and Sophia Kingshill bring together many of the finest and most intriguing: stories of heroes and bloody feuds, tales of giants, fairies, and witches, and accounts of local customs and traditions. Their range extends right across the country, from the Borders with their haunting ballads, via Glasgow, site of St Mungos miracles, to the fateful battlefield of Culloden, and finally to the Shetlands, home of the seal-people.

More than simply retelling these stories, The Lore of Scotland explores their origins, showing how and when they arose and investigating what basis if any they have in historical fact. In the process, it uncovers the events that inspired Shakespeares Macbeth, probes the claim that Mary Kings Close is the most haunted street in Edinburgh, and examines the surprising truth behind the fame of the MacCrimmons, Skyes unsurpassed bagpipers. Moreover, it reveals how generations of Picts, Vikings, Celtic saints and Presbyterian reformers shaped the myriad tales that still circulate, and, from across the country, it gathers together legends of such renowned figures as Sir William Wallace, St Columba, and the great warrior Fingal. The result is a thrilling journey through Scotlands legendary past and an endlessly fascinating account of the traditions and beliefs that play such an important role in its heritage.

About the Authors

Jennifer Westwood was born in 1940 and studied English Language at Oxford, followed by Medieval Icelandic at Cambridge. A long-time member of the Folklore Society, she served as editor of FLS Books and also the journal Folklore. Her books include Albion: A Guide to Legendary Britain (1985), Gothick Cornwall (1992), Lost Atlantis (1997), On Pilgrimage (2003) and The Lore of the Land (2005, with Jacqueline Simpson). Sadly, she died in 2008.

Sophia Kingshill is a writer, editor and researcher. She has contributed to folklore publications and her plays have been performed in Scotland, England and Norway. She lives in London.

To Jennifer Westwood (19402008)

and to Peter Kingshill (19222008)

INTRODUCTION

When my mother Jane was about eight years old, she went to stay in Perthshire with a close friend of the family, Katharine Briggs, in those days not a well-known folklorist, but already a commanding presence. Katharine took her for a walk on the hills one evening, and as the mist and darkness rose around them she recited, in low tones of menace punctuated with expressive wails, the rhyme of The Strange Visitor. The story tells of a woman sitting alone one night and wishing for company, which soon comes in the form of a pair of bony feet, followed by a pair of bony shins, knees, and so on until the entire skeleton is present, and when asked what it has come for, shouts FOR YOU! My mother was so frightened that she was ill for a fortnight.

The Strange Visitor is a famous tale, printed in Robert Chamberss collection of Popular Rhymes of Scotland (1870), and several localised legends have much the same plot, as described for example at KILNEUAIR (Argyllshire & Islands) and DORNOCH CATHEDRAL (Northern Highlands). Scottish folklore is full of terror. In tradition the landscape is peopled with evil beings, fairies or trows which kidnap mothers and children, kill livestock, and whisk the unwary on journeys through the air, while Water-horses and Kelpies are always in wait to lure travellers into deep lochs or rivers or to tempt innocent girls to their doom. Much Scottish legend reflects a hostile though beautiful environment, one in which for centuries survival was a never-ending struggle against harsh land and hungry sea.

To personify the forces of nature is a way of understanding them, and stories which explain the world help to give people (if only in imagination) some control over their surroundings and circumstances. That is the essence of folklore, by definition the lore or body of traditions and knowledge shared by the folk ordinary people as distinct from educated opinions passed down by those in authority. Although legends may not have been considered as literally true, they gave structure and guidance, bridging the gap between human beings and the invisible powers around them. It is doubtful how much anyone ever believed that stillbirth or cot-death were caused by baby-snatching fairies, but, as mentioned at CAERLAVEROCK (Dumfries & Galloway), it is certain that straw crosses or steel pins were widely used as protection against the marauders, just as today we often touch wood without any real conviction that bad luck will be averted.

Other tales embodied entirely practical concerns of a kind shared by parents throughout history, to keep their children away from deep water or dangerous animals and to warn their daughters against taking up with strange men. Where plain advice might have been forgotten, a horrid anecdote of disembowelment by the Water-horse must surely have stayed in the mind.

While the hardships and perils of day-today existence may have suggested the presence of unseen and unfriendly creatures, the landscape of Scotland evokes a mightier shaping force, dramatised in legends of devils hurling rocks from the heights or nature spirits flooding the valleys, as at CRAIL (Central & Perthshire) and LOCH AWE (Argyllshire & Islands). Ancient myth attributes creation to the gods, but the folklore of later ages tends to shift focus from the heavens to intermediate powers, crediting demons, giants, or even certain humans with the ability to move mountains. Holy martyrs are said to have made springs flow from the ground, and not only saints such as Columba but champions like William Wallace are reported to have left the prints of their feet or hands in solid rock, marking the land forever with their presence. Other sites are linked with magicians, scholars and scientists from the Middle Ages to the Enlightenment who were remembered in popular tradition as wizards, and reputed to have diverted rivers or cleaved the hills with the help of their arcane knowledge.

Legend offers a means of interpreting history as well as geography, and Scotlands battle-torn past has substantially inspired its folklore. Invasion, civil war, and discord with England, clan feuds, border raids, and religious persecution have shaped the countrys mythology. Towering heroes are remembered at key moments of their destiny, like Robert the Bruce watching the spider at UGADALE (Argyllshire & Islands), and demonized villains such as Robert Grierson, Laird of Lag, are said to have suffered damnation for their part in suppressing seventeenth-century Presbyterian dissent (see ).

Next page