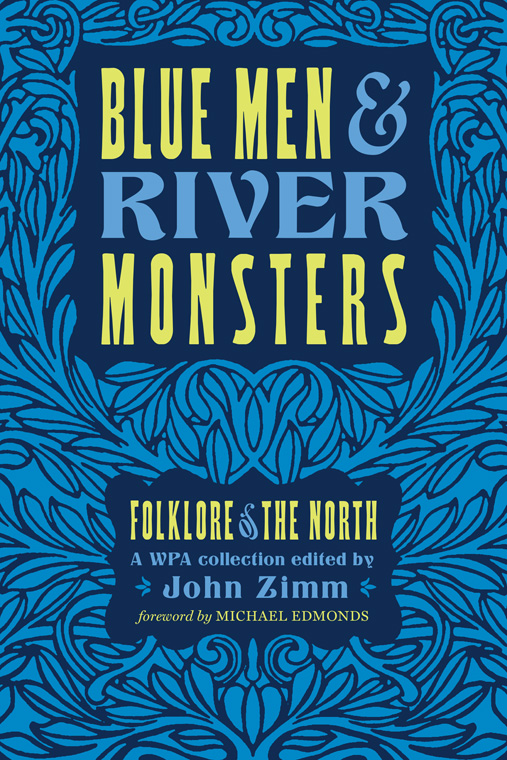

BLUE MEN & RIVER MONSTERS

FOLKLORE OF THE NORTH

A WPA collection

Edited by John Zimm Foreword by Michael Edmonds

WISCONSIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY PRESS

Published by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press

Publishers since 1855

2014 by the State Historical Society of Wisconsin

For permission to reuse material from Blue Men and River Monsters: Folklore of the North, ISBN 9780-870206702 and ebook ISBN 9780-870206719, please access www.copyright.com or contact the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. (CCC), 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 9787508400. CCC is a not-for-profit organization that provides licenses and registration for a variety of users.

wisconsinhistory.org

Photographs identified with WHi or WHS are from the Societys collections; address requests to reproduce these photos to the Visual Materials Archivist at the Wisconsin Historical Society, 816 State Street, Madison, WI 53706.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication

Blue men and river monsters : folklore of the north / edited by John Zimm ; foreword by Michael Edmonds.

pages cm

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-87020-670-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-87020-671-9 (ebook) 1. FolkloreWisconsin. 2. WisconsinSocial life and customs. 3. Frontier and pioneer lifeWisconsin. I. Zimm, John, editor.

GR110.W5B58 2014

398.209775dc23

2014007545

CONTENTS

T his book was conceived eight decades ago, during the heart of the Great Depression. In 1935, with nearly 10 million Americans out of work, Congress established the Works Progress Administration to provide jobs. When WPA director Harry Hopkins was criticized for giving work to writers and artists, he snapped, Hell, theyve got to eat like other people.

Federal Writers Projects were soon springing up around the nation. Each was charged with preparing a travel guide to its own state that captured the native and folk backgrounds of rural localities. WPA editors encouraged staff to interview farmers, factory workers, immigrants, former slaves, Indians, and other Americans typically left out of traditional travel guides.

In October 1935, WPA officials appointed Charles Brown to head the Wisconsin writers project. As museum director at the Wisconsin Historical Society, Brown had been collecting artifacts and running archaeological digs for three decades. He knew old settlers and tribal elders all around the state who recalled oral traditions. Brown agreed to supervise the project if he could keep his museum job and have someone else oversee the new office day to day.

Washington initially required writers project offices in every city of ten thousand or more, from which writers and investigators will comb the neighboring territory for color and historic information. In Wisconsin, large offices opened in Milwaukee and Green Bay, and by early 1936 about 140 staff around the state were gathering information for the proposed guidebook.

One of Browns first and wisest decisions was to hire Dorothy Miller, a thirty-nine-year-old single mother, to head the Wisconsin

Miller quickly assembled a team of unemployed women to save the states vanishing oral heritage. It consisted of several field interviewers assisted by two typists and various clerical staff; at any given time it totaled ten to fifteen workers. Although some men were also employed on the project, in her office memos Miller affectionately called them my girls.

Their wages ranged from $62.50 to $83.50 a month, on which some of them had to support families. WPA workers were often scorned by the public as freeloaders and repeatedly laid off when Congress or WPA administrators shifted funding priorities. Yet in the words of one Wisconsin staff member, They bore poverty, opprobrium, and the recurrent strain of the quota cuts and shake-ups without losing their self-respect, their respect for one another, or their keenness for and belief in what they were doing.

Miller and her staff began in the spring of 1936 by unearthing folklore hidden in obscure books, pamphlets, and newspaper files at the Wisconsin Historical Society. Then they drove around the state to interview elderly residents in Shawano, Rice Lake, La Crosse, Prairie du Chien, and Dane and Door Counties. Gregg Montgomery and Dorothy Potter appear to have been the principal field-workers, with Coryl Moran and Jane Olson also conducting some of the interviews. Three of the four had grown up working class; two were single working women like Dorothy Miller herself. In six months they talked to more than 300 people, who provided more than 1,000 folktales, 3,000 songs, 1,500 games and superstitions, and 9,000 proverbs.

But that was just the beginning. Over the course of the entire

Although the material was largely collected from living people, it passed through several stages of editing. The field-workers handwritten notes were recast into grammatical sentences as they were typed. Carbon copies were marked up by editors mainly interested in their potential use for the state guide. By the time final clean copies emerged, the speech of local informants had usually been rearranged and polished by the project staff.

In Washington, folklorist John Lomax congratulated the Wisconsin team for collecting an amazing amount of good material.... The work has been carefully and thoroughly done. Miller broadcast shows about Wisconsin folklore on the radio and published fifty articles in newspapers around the state and national magazines. She provided two hundred folktales for use in the Wisconsin guide, sent exhibits to Washington in 1936, and organized Wisconsins participation in the National Folk Festival in Chicago in 1937. She traveled as far as New Orleans to give presentations based on the material her girls had amassed.

But apart from Millers close-knit group, the Wisconsin writers project fell apart. The county and district units broke down almost immediately, editor Harold Miner wrote afterward. Only the offices at Milwaukee and Green Bay (which had so far concealed its ineptitude by a great show of energy) survived the first six months. Miner recalled that they had merely assembled a large accumulation of inaccurate and inane material, all elaborately filed and cross-indexed. When I left Madison, this mass of material was stored (for it could not be destroyed, since it was government property) in the attic of a condemned school building, and everyone hoped the rats would eat it.

Miller, on the other hand, worked hard to see that the best of the oral tales were preserved in print. Within eighteen months she issued

Early in 1937, after Browns wife died, he fell in love with Dorothy Miller, and on April 7 they were married while en route to a folklore conference. For the next decade, they gave lectures, wrote articles, published books, and traveled to professional meetings together, as well as parenting a menagerie of stepchildren and having a daughter of their own.

Brown had never been able to give the Wisconsin writers project the attention it deserved, and it was plagued by incompetent managers, administrative blunders, labor disputes, and bad press. In the fall of 1937, a disgruntled former employee publicly denounced Brown for hiring his own son and marrying a member of his staff. In a scathing letter to the press, the employee demanded to know how WPA officials could be so exceedingly kind and generous with federal funds to one family already pretty well financed by the state of Wisconsin.

Though his superiors had approved his actions, Brown resigned in embarrassment in November 1937. Dorothy followed him out the door. Heading a Federal Writers Project in Wisconsin, he wrote to a colleague, as I did for two years much against my own wishes and in addition to my other work and at a real monetary loss to myself, was a very ungrateful undertaking not properly or fully appreciated here or in Washington.

Next page