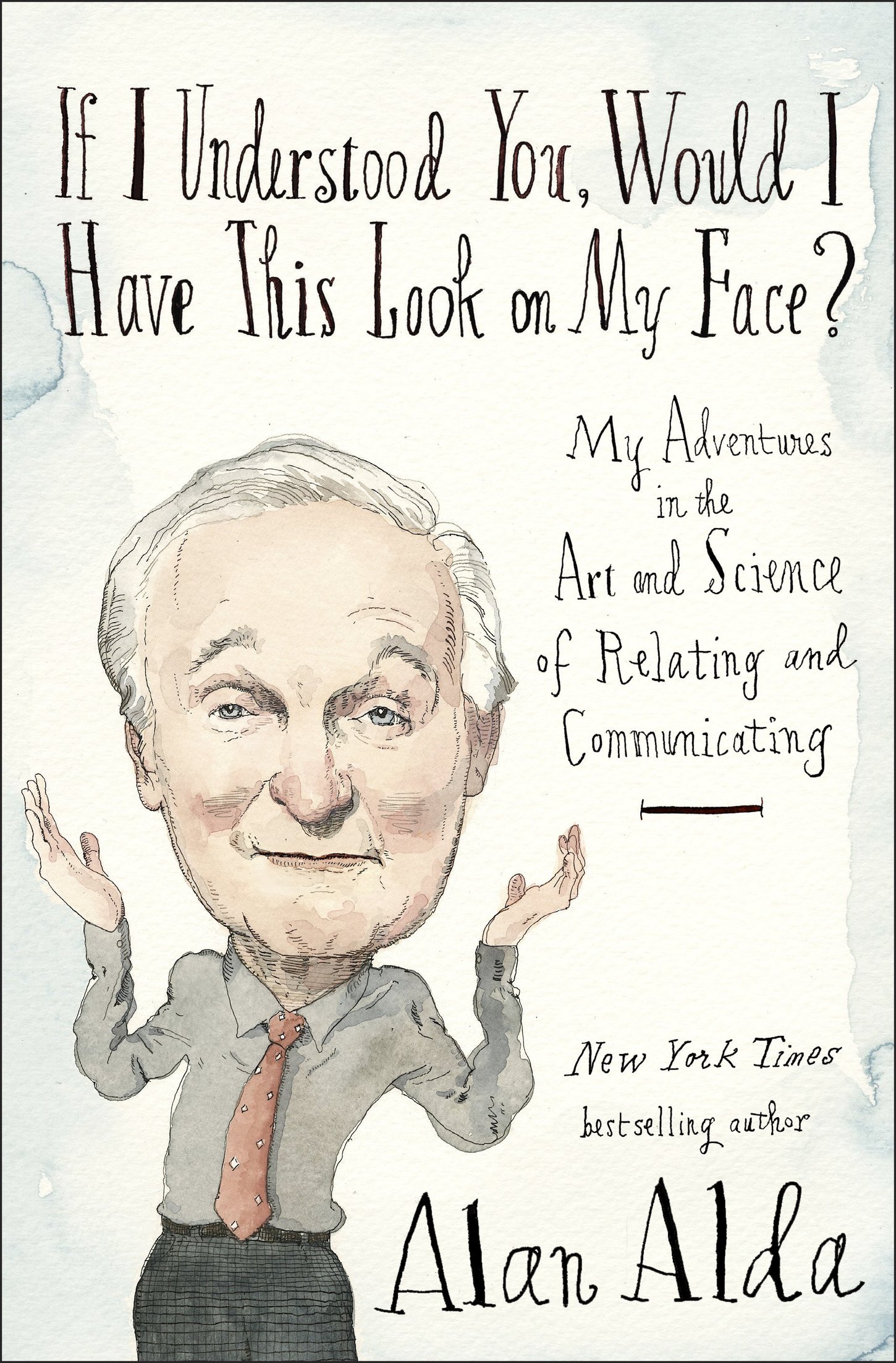

When it finally became clear to me that I often didnt understand what people were telling me, I was on the road to somewhere good.

Some of the things they were trying to communicate were complicated, but that didnt seem like a good reason why I didnt understand them. If they could understand these things, why couldnt I? An accountant would tell me about the tax code in a way that made no sense. A salesman would explain an insurance policy that didnt seem to have a basis in reality. It wasnt any consolation when I came to realize that pretty much everybody misunderstands everybody else. Maybe not all the time, and not totally, but just enough to seriously mess things up.

People are dying because we cant communicate in ways that allow us to understand one another.

That sounds like an exaggeration, but I dont think it is.

When patients cant relate to their doctors and dont follow their orders, when engineers cant convince a town that the dam could break, when a parent cant win the trust of a child enough to warn her off a lethal drug, they can all be headed for a serious ending.

This book is about what we can do about that; about how I learned what I believe is the essential key to good communication, and to relating to one another in a more powerful way. Surprisingly, I found that key in my training and experience as an actor, and its helped me teach others how to communicate better, especially about things that are difficult to talk about or hard to grasp.

IT ALL BEGAN WITH MY TOOTH

The dentist had the sharp end of the blade inches from my face.

It was only then that he chose to tell me what he was seconds away from doing to my mouth. There will be some tethering, he said.

I froze. Tethering? My mind was racing. What does he mean? How could the word tethering apply to my mouth? He seemed impatient and I didnt want to annoy him, but he was, after all, about to put a scalpel in my mouth. I asked him what he meant by tethering. He looked surprised, as if I should know the meaning of a simple word. He began barking at me. Tethering, tethering! he said.

I was well over the age of fifty, and certainly old enough to ask him to put the knife down and answer a few questions. But there he was in his priestly surgeons gown, and getting increasingly impatient. Okay, I said, a little too accommodatingly. Then he put the scalpel into my mouth and cut.

I didnt realize it at the time, but this was a watershed moment for me.

For the rest of my life, I would be living with the results of these few seconds of poor communicationin ways that were both good and bad.

First the bad: A few weeks later, I was acting in a movie. The camera was in close on me as I smiled. A relaxed, happy smile. After the take, the director of photography came over, looking puzzled, and said, Why were you sneering? I thought you were supposed to smile.

I was smiling, I said.

Nooo. Sneering, he said.

I looked in a mirror and smiled. I was sneering.

My upper lip drooped lazily over my teeth, and no matter how I tried I couldnt form an actual smile. The problem was my frenum. I no longer had one.

In case youre not familiar with your frenum, its just above your front teeth, between the gum and the inside of the upper lip. If you put your tongue at the top of your gums above your front teeth, youll feel a slim bit of connective tissue, or at least you will if a barking dentist hasnt been in your mouth. The tissue is called the maxillary labial frenum, and he had severed mine.

The procedure was one he had invented. It enabled him to pull a flap of gum tissue down over the socket of the front tooth he had extracted. The idea was to give the socket a fresh blood supply while it healed. He was proud of his invention and it seemed perfectly suitable for the gums blood supply, but not so good for using my face in movies. Without my frenum, my upper lip just hung there like a scalloped drape in the window of an old hotel.

After the movie shoot, I called him and explained with saintly patience that I made a living with my face and sometimes I needed one that could smile.

His response was curt. I told you there were two steps to the procedure. I havent done the second step yet. I was a little reluctant to let him do the second step. Maybe this time hed have a go at the frenum under my tongue. I didnt have many frena left, and he seemed to have an unnatural attraction to them.

A couple of weeks later, I got a letter from him that was formal and cold. No hint that he was anything like sorry that I was feeling a little mutilated. It was clear that the point of the letter was to lay out his defense and discourage a possible lawsuit. Until I saw the tone of his letter, I hadnt even thought of suing (and I never did)but if he wanted to avoid a suit, he was going about it in exactly the wrong way.

The experience wasnt all bad, though. For one thing, I learned to work around my frenum-less smile, and my new, slightly off-kilter grin enabled me to play a whole new set of villains. Even better, that moment in the dentists chair was useful in ways I wouldnt understand at the time.