Never Have Your Dog Stuffed is a work of nonfiction.

Some names and identifying details have been changed.

Copyright 2005 by Mayflower Productions, Inc.

Frontispiece photograph copyright Norman Seeff

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

RANDOM HOUSE and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

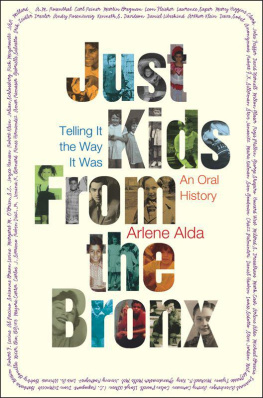

Alda, Alan

Never have your dog stuffed: and other things Ive learned/Alan Alda.

p. cm.

1. Alda, Alan. 2. ActorsUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

PN2287.A45A 3 2005 792.02'8'092dc22 2005050135

[B]

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

www.atrandom.com

eISBN: 978-1-58836-492-0

v3.0_r2

Act one: Get your hero up a tree.

Act two: Throw rocks at him.

Act three: Get him down again.

attributed to GEORGE ABBOTT,

on playwriting

Contents

chapter 1

DONT NOTICE ANYTHING

My mother didnt try to stab my father until I was six, but she must have shown signs of oddness before that. Her detached gaze, the secret smile. Something.

We were living in a two-room apartment over the dance floor of a nightclub. My father was performing in the show that played below us every night. We could hear the musical numbers through the floorboards, and we had heard the closing number at midnight. My father should have come back from work hours ago.

My mother had asked me to stay up with her. She was lonely. We played gin rummy as the band below us played Brazil and couples danced through the haze of booze and cigarette smoke late into the night.

Finally, he came in. She jumped up, furious. Where have you been? she screamed. Even at the age of six, I could understand her anger. He worked with half-naked women and came home late. It wasnt crazy to be suspicious.

She told him she knew he was sleeping with someone. He denied it. You are! she screamed. He denied it again, this time impatiently.

You son of a bitch! she said. She picked up a paring knife and lunged at him, trying to plunge it into his face. This was crazy.

He caught her by the wrist. Whats the matter with you?

They struggled over the knife as I pleaded with them to stop. When he forced her to drop it, I picked up the knife and rammed it point first into the table so it couldnt be used again.

A few weeks later, the three of us were at the small table by the kitchenette, eating.

I was playing with the knives and forks in the silverware tray. I found a paring knife with a bent point and I looked up at my mother: Remember when I stuck the knife in the table?

When?

When you wanted to stab Daddy?

She smiled. Dont be silly. I never did that. I love Daddy. You just imagined that. She laughed a lighthearted but deliberate laugh. I looked over at my father, who looked away and said nothing.

I knew what I saw, but I wasnt supposed to speak about it. I didnt understand why. I didnt understand how this worked yet.

Gradually, I came to learn that not speaking about things is how we operated. When we would visit another family, my mother was afraid I might embarrass them by calling attention to something like dust balls or carpet stains. As we stood at the door, waiting for them to answer our knock, she would turn to me, completely serious, and say, Dont notice anything.

We had a strange list of things you didnt notice or talk about. The night the country was voting on Roosevelts fourth term, my father came back from the local schoolhouse and I asked him whom hed voted for. Well, he said with a little smile, we have a secret ballot in this country. I didnt ask him again, because I could see it was one of the things you dont talk about, but I couldnt figure out why there was a law against telling your children how you voted.

One thing we never talked about was mental illness. The words were never spoken between my father and me. This wasnt the policy just in our own family. At that time, mental illness was more like a curse than a disease, and it was shameful for the whole family to admit it existed. Somehow it would discredit your parents, your cousins, and everyone close to you. You just kept quiet about it.

How much easier it could have been for my father and me to face her illness together; to compare notes, to figure out strategies. Instead, each of us was on his own. And I alternated between thinking her behavior was his fault and thinking it was mine. Once I learned there was such a thing as sin and I entered adolescence and came across a sin I really liked, I began to be convinced that my sins actually caused her destructive episodes. They appeared to coincide. This wasnt entirely illogical, because they both tended to occur every day. I was convinced I held a magic wand that could damage the entire household.

Like the earliest humans, I put together my observations and came up with a picture of how things worked that was as ingenious as it was cockeyed. And like the earliest people, in my early days I was full of watching and figuring. I was curious from the first momentsnot as a pastime, but as a way to survive.

As I sat at the kitchen table that night, looking at the paring knife with the bent point, I was trying to figure out why I was supposed to not know what I knew. I was already wondering: Why are things like this? Whats really happening here?

There was plenty about my world to stimulate my curiosity. From my earliest days, I was standing off on the side, watching, trying to understand a world that fascinated me. It was a world of coarse jokes and laughter late into the night, a world of gambling and drinking and the frequent sight of the buttocks, thighs, and breasts of naked women.

It seemed to me that the world was very interesting. How could you not want to explore a place like this?

chapter 2

NAKED LADIES

I was three years old. It was one in the morning, and I was walking down the aisle of a smoky railroad car. I liked the feel of the train as it lurched and roared under my feet. My father was in burlesque, and he and my mother and I traveled from town to town with a company of comics, straight men, chorus girls, strippers, and talking women. As I moved down the aisle, not much taller than the armrests, I watched the card playing, the dice games, the drinking and joking, late into the night.

I would fall asleep on a makeshift bed made of two train seats jammed together. A few hours later, my mother would wake me as the train pulled into Buffalo or Pittsburgh or Philly. Id sit up groggily and gaze out the window as she pulled on my woolen coat and rubbed my face where the basket weave of the cane seat had left a pink latticework on my cheek. As the train crept slowly into the town, I could see the water towers, the factories, the freight trains jockeying across the rail yards in the gray early light. This would be the first sight Id have of every city wed travel to, and my heart would beat with excitement.

And then, five or six times a dayat almost every showI would be standing in the wings, watching. There would be an opening number in which my father stood on the side of the stage and sang while chorus girls danced and showed their breasts. The person who performed this job in burlesque was called, with cheerful clarity, the tit singer.

Next page