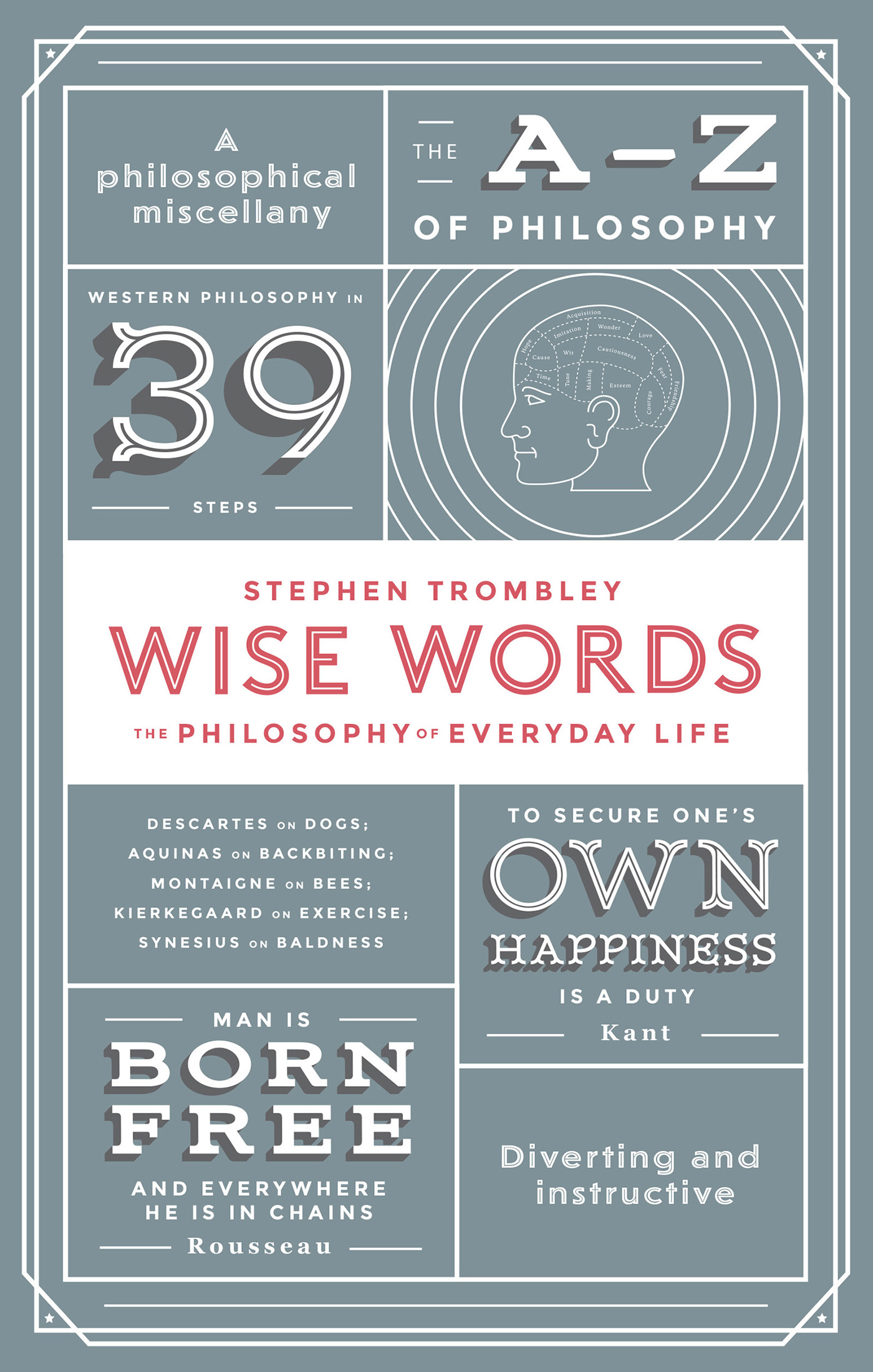

WISE WORDS

The Philosophy of Everyday Life

Stephen Trombley

www.headofzeus.com

Stephen Trombley has mined two and a half millennia of Western thought for observations that reflect the seriousness, the joy and the strangeness of human existence. Via thirty-nine eclectic themes, he journeys across the history of philosophy, from ancient Greeks to contemporary continentals, from idealists to existentialists and from empiricists to analytics.

For Colleen Murphy, with love and gratitude

Contents

The aim of this little miscellany is both to amuse and to inform the reader as I have been amused and informed while writing it. I was generously given free rein to gallop across the whole spectrum of subjects covered by philosophy, and back and forth in time, to inquire what philosophers thought about those subjects in any given era. It has been a wild journey, and Ive done my best here to give an account of it.

While there has been some method to my work, whimsy is the chief criterion I employed in deciding what subjects to write about and which philosophers thoughts on them to include. I present some of the greatest minds in history reflecting on topics that might be found in an agony column: Advice, Backbiting, Day Jobs, Drugs, Extraterrestrials, Friendship, Fun, Haircuts, Laughing, Sex, Sport and Walking. I also gather their thoughts on subjects which we might more usually expect to be treated in a philosophy book: Belief, Consciousness, Duty, Freedom, Intuition, Truth, War and others like them.

If I were composing an anthology of philosophy, as opposed to a miscellany, I would have a certain duty to the reader to be inclusive. But Im not and I dont. Because its a miscellany, I am at liberty to include and exclude anything that takes my fancy. My method has been this: each treatment of a subject under discussion here usually begins with the thoughts of the ancient Greeks, then moves progressively to the present. One reason why the Greeks get first shout is that they were the first thinkers in the West to consider these topics. After the Greeks, Roman, scholastic, Renaissance, Enlightenment, idealist, naturalist, empiricist, analytic, continental and other thinkers all get a look-in. I leave it to the reader to decide, as we work our way through the ages, whether subsequent thinkers improved upon Greek ideas. In many cases valuable clarification and introduction of new subtleties has occurred. In other cases, later thinking has offered more obfuscation than explication ( see pages 28794).

The ancient Greeks are usually clear in their definition of a problem and the proposed solution. There was for centuries a kind of unspoken rule among subsequent philosophers that they, too, should strive for clarity in their prose, and this continued up until the late eighteenth century and the rise of German idealism. Then, philosophers like G. W. F. Hegel earned a well-deserved reputation for dense and opaque writing; for the introduction of jargon and unnecessary neologisms. The result is often as in the case of the twentieth-century German thinkers Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger writing that is nothing less than execrable. This tendency caught hold, and marks much of what is called continental philosophy in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. My aim throughout Wise Words has been to find passages in the works of even the most difficult philosophers that are clear and which speak directly to a non-professional audience on subjects that might concern them, but whose concern is not great enough to justify hours of wading through turgid text.

One might ask why Ive bothered to do this, given that it is no small task. I could reply that I took it on in the spirit of the Roman poet Horace, who famously declared that Poets wish either to instruct or to delight. One can also combine the two, and that is my intention. In my years of reading philosophy I have always found it instructive, if sometimes a hard slog. But on many occasions I have been delighted charmed with the observations, arguments or conclusions of philosophers. It is those charmed moments that I wish to share here.

A final word about the modest apparatus of this book. Because I presume it is to be sampled as a dipping-in book rather than read straight through, I had to find a way of indicating the relevant eras in which individual thinkers were active without repeating myself ad infinitum. The solution is simple: a directory of philosophers consulted, including their dates, nationality and a brief description, which appears at the back of the book. I have also included a bibliography of secondary works cited, a list of internet sites where classic philosophy texts can be consulted and a brief note about online philosophy encyclopaedias. Since many of the ideas discussed by philosophers under one heading have relevance to other entries in the book, I have included a system of cross-references. Each development of an idea within sections is assigned a roman numeral. This way, cross-references may be made in the style ( see FRIENDSHIP iv).

Philosophy is an endless task; even a lifetimes reading would give us an incomplete account of it. I make no claim to inclusiveness in this present exercise. However, I do hope that anyone who has absorbed its contents might have gained at least a passing acquaintance with Western philosophers and their ideas, and be stimulated to inquire further.

Aut prodesse volunt aut delectare poetae. Ars Poetica ( c .19 BC ).

i

SOCRATES CONSULTED THE ORACLE AT DELPHI.

We know this from Xenophon, one of the masters lesser-known students. Xenophon tells of it in The Memorabilia ( c. 371): The divinity, said he, gives me a sign. Further, he would constantly advise his associates to do this, or beware of doing that, upon the authority of this same divine voice; and, as a matter of fact, those who listened to his warnings prospered, whilst he who turned a deaf ear to them repented afterwards.

Xenophon reports that Socrates did not advise seeking the oracles advice on the ordinary necessities of life; to do so, he taught, was a type of profanity. In everyday matters he urged his students to Act as you believe these things may best be done. But, in the case of those darker problems, the issues of which are incalculable, he directed his friends to consult the oracle, whether the business should be undertaken or not.

As an advice-giver, Socrates practised what he preached. For instance, he counselled thrift. Xenophon again: a man must work little indeed who could not earn the quantum which contented Socrates. He was frugal where food and drink were concerned; but Xenophon noted how, in frugality, Socrates found pleasure. Of food he took just enough to make eating a pleasure the appetite he brought to it was sauce sufficient. The same with drink: seeing that he only drank when thirsty, any draught refreshed. Overindulgence in food and drink, said Socrates, is bad for stomachs, brains, and soul alike. And it is not only physical health that is promoted by moderation in food and drink: ones wits were also preserved: It must have been by feasting men on so many dainty dishes that Circe produced her pigs.

Thoughts of Circe lead Xenophon to reflect on Socrates advice regarding male sexual desire for women. His advice was to hold strongly aloof from the fascination of fair forms: once lay finger on these and it is not easy to keep a sound head and a sober mind. He likened a womans kiss to that of a poisonous spider bite: