The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2002, 2015 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 2015

Printed in the United States of America

21 20 19 18 17 16 15 1 2 3 4 5 6

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-27618-2 (paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-27621-2 (e-book)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226276212.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Klinenberg, Eric.

Heat wave : a social autopsy of disaster in Chicago / Eric Klinenberg.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-226-27618-2 (paperback : alkaline paper) ISBN 978-0-226-27621-2 (e-book) 1. Older disaster victimsIllinoisChicago. 2. DisastersSocial aspectsIllinoisChicago. 3. Older peopleServices forIllinoisChicago. 4. Older peopleIllinoisChicagoSocial conditions. 5. Heat waves (Meteorology)IllinoisChicago. I. Title.

HV1471.C38K585 2015

363.34992dc23

2015002922

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

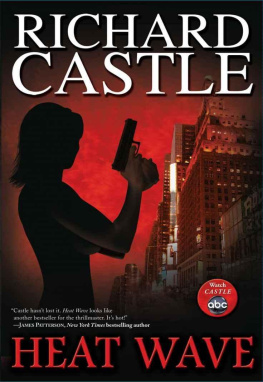

HEAT WAVE

A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago

Second Edition

Eric Klinenberg

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS

CHICAGO AND LONDON

For my parents, Rona Talcott and Edward Klinenberg.

And for Herbert J. Davis, whose incisive mind and generous spirit will always provide inspiration.

Contents

Illustrations

FIGURES

TABLES

Acknowledgments

I did not intend to study Chicago when I moved to Berkeley in 1995, but once I recognized my habit of writing about the metropolis from afar I understood that the city I had always claimed as my home had also made a claim on me. I am fortunate that so many other Chicagoans are similarly bound to the city. Their attachment is the basis for an unusually strong collective conscience, and I suspect that it is also the condition that makes conducting social research in Chicago such a meaningful experience. I have many people to thank for their contributions to this book, and none deserve more credit than those who actively participated in the research: the senior citizens, block club participants, community activists, political officials, city employees, medical workers, social service providers, and journalists who opened their doors to me and shared either memories of the heat wave or personal accounts of their everyday experiences in the city.

Sociology is better suited for explaining and understanding social processes and events than for denigrating or celebrating particular individuals or groups, so although many complex personalities and difficult social problems appear in this account, no singular heroes or villains come to light in the analysis I offer here. If the social autopsy of the 1995 heat wave uncovers some of Chicagos hidden blights, it does so not to impugn or embarrass any people or institutions but to make sense of and call attention to emerging forms of isolation, deprivation, and vulnerability that deserve critical scrutiny. This book is both an invitation to consider the ways we live and die in the cities of today, and a challenge to imagine how we will transform and inhabit the cities of tomorrow.

It would have been impossible to conceive of this projectlet alone to conduct the research for itwithout the training I received as a graduate student in sociology at the University of California, Berkeley. I would like to thank my dissertation committee, Loc Wacquant, Manuel Castells, Michael Rogin, Martn Snchez-Jankowksi, and Margaret Weir, as well as two readers, Claude Fischer and Nancy Scheper-Hughes, who acted as full-fledged committee members even though they were not formal participants. Lawrence Cohen, Gil Eyal, Neil Fligstein, Arlie Hochschild, Mike Hout, Tom Laqueur, and Sam Lucas added insight and support.

Fellow graduate students at Berkeley created an exciting intellectual environment. In particular, my thanks go to Kimberly McClain DaCosta, Daniel Dohan, Rodney Benson, Jeff Juris, Shai Lavi, Andrew Perrin, Onesimo Sandoval, Jessica Sewell, and Matt Wray for knowing how to mix criticism with compassion and companionship so that we could make it through our dissertations and live well in the process. Colleagues I got to know before arriving in California, especially Barbara Epstein, Sam Kaplan, David Lewis, and Louise Jezierski, provided wise counsel and friendship. The members of SAGS kept me on my toes while the rest of Berkeley rested, and made my small jumps forward feel like giant leaps.

Several institutions provided me with resources and the time, space, and critical attention that make scholarship possible. The early research and writing for this project were funded by fellowships from the Jacob Javits graduate fellowship program and the National Science Foundation, as well as small grants from the Berkeley Humanities Division and Phi Beta Kappa. An Individual Projects Fellowship from the Open Society Institute offered the final boost that I needed to continue my research and craft this book. I am grateful to OSI administrators Gail Goodman, Joanna Cohen, Gara LaMarche, JoAnn Mort, and Pamela Sohn for their support, and to OSI Fellows Jamie Kalven, Eyal Press, Jonathan Schorr, and Elaine Sciolino for helping me engage with the world outside of academe.

When I did my fieldwork in Chicago, Edward Lawlor welcomed me as a visiting scholar at the University of Chicagos Center for Health Administration Studies and introduced me to a network of local organizations concerned with health and aging. I spent six months in Paris at the Center for European Sociology of the cole des Hautes tudes en Sciences Sociales, where I learned new approaches to the study of politics, culture, and the media through seminars and discussions with Patrick Champagne, Remi Lenoir, Dominique Marchetti, and Pierre Bourdieu. I spent my last year in Berkeley working in ideal conditions at the Center for Urban Ethnography. I received excellent feedback from scholarly audiences at many academic events, including colloquia at the sociology departments of the University of California, Los Angeles, the University of Chicago, New York University, Northwestern University, and the University of Lyon-Lumiere II; conference presentations at the American Anthropological Association meetings in 1997 and the American Sociological Association meetings in 1998; and a public lecture in the Medicine, Markets, and Bodies series at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1999. The influences of these institutions are apparent throughout this book.

I wrote the final version of the manuscript at Northwestern University, where colleagues in the Department of Sociology and the Institute for Policy Research offered fresh perspectives that allowed me to see beyond the parameters of my initial work. Soon after I returned to Chicago in 2000, Arthur Stinchcombe gave me useful suggestions for strengthening the theoretical apparatus that holds the book togethersometimes, indeed, less is more. Jeff Manza delivered on his promise to read each chapter that I dropped at his office door and convinced me that the best days of public sociology might still be ahead of us. And although Mary Pattillo likes to say that I would have finished the book months earlier had we not gotten caught up in so many long conversations and debates, the final product is better because of what I learned during our exchanges. Other colleagues at Northwestern have provided valuable feedback on portions of the manuscript. Thanks go to Nicola Beisel, Fay Cook, Gary Alan Fine, Benjamin Frommer, Jennifer Light, Ann Shola Orloff, Ethan Shagan, and Wes Skogan for their many contributions, and to Ellen Berrey, Liz Raap, Scott Leon Washington, and Pete Ziemkiewicz for their expert research assistance.

A number of friends and colleagues outside Chicago have also given me trenchant criticism and advice. Jack Katz and Richard Sennett read the entire manuscript and helped me refine various arguments and ideas. Evelyn Brodkin, Jodi Cantor, Dalton Conley, David Grazian, Doug Guthrie, and Sudhir Venkatesh offered suggestions on individual chapters. Paul Dimaggio, Serge Halimi, and Paul Willis provided sharp editorial comments and substantive feedback in reviews of journal articles about the heat wave that I previously had published in

Next page