CHAPTER ONE

Peer Pressures

INVERGORDON, SCOTLAND, MONDAY, 14 SEPTEMBER 1931

The midshipman glances at the picket boats bow wave and frowns. He stares at the froth and fury of spray as the waters of the Cromarty Firth are thrust aside. He frowns again when he senses a shift in the accustomed rhythm of the boats motion; the vessel lurches and groans as the sea slaps against the hull. He concludes, however, that the trouble is probably illusory, just a figment of his imagination. Normally thrilled by the sights and sounds of the seagoing life, Midshipman Alan William Frank Sutton is unhappy at present, unable to forget the immediacy of his invidious position. He gulps the sea air and shivers; he draws the protective layers of his navy-issue coat closer to his neck. In the distance beyond Invergordon, the early-evening light barely allows him to make out the line of high ground, although from time to time he can glimpse the hills of Easter Ross which, he thinks, look as uninviting as the Cromarty waters they overlook.

Midshipman Sutton knows that he must be strong-minded. Signs of weakness could lead to serious trouble; his personal doubts must be kept to himself. He has decided that his best course will be to display an air of quiet confidence one of firm authority. He will make it understood that any acts of indiscipline, however minor, will not be tolerated. The matter, though, is not easy for a young man of just nineteen years, even one with a natural sense of leadership. This is, after all, his first posting with the Royal Navy. He is about to confront be forced to confront a situation which is hardly textbook for a new officer straight from his year of training as a special entry cadet at HMS Erebus , Devonport.

He glances once more at the bow wave. The gossamer lure of the sea seems surreal; the waters glisten and chatter as if in conversation with the gulls. He raises his eyes. For a moment he gazes at the gulls. He ponders about them, what curious creatures they are. He sees one of them dive towards the brass-funnelled picket boat and he recalls the advice given by an instructor at Devonport Lieutenant Matthew Slattery. Never refer to them as seagulls, the lieutenant had said one time. Theres no such thing, Mister Sutton. The instructor had stared sternly at the young cadet. Thats the kind of terminology used by ignorant landlubbers.

So, muses Midshipman Sutton just now, what the hell are these then? Black-headed gulls, great black-headed gulls, herring gulls? Goodness knows. Scottish herring gulls, perhaps. They look a bit Scottish somehow. Maybe they eat haggis; theyll be wearing kilts next. The midshipman chuckles to himself and he momentarily puts present worries to the back of his mind. He remembers Lieutenant Slattery as an exceptionally good man: one of the old school, someone who would go far. As he surmises the prospects of the future Admiral Sir Matthew Slattery, and as he ruminates, Midshipman Sutton recalls the passing-out ceremony at Devonport last month. His mother had attended, and so had his brother, Dudley. Not his father, though.

If only...

But perhaps, in spirit, he had been there.

On that day at Devonport, Instructor Lieutenant Slattery had been a model host. He had known about Cadet Suttons background, and with the natural urbanity of an officer and a gentleman he had welcomed the family into another family that of the Royal Navy: bigger and broader, but a family nevertheless. Lieutenant Slattery was aware of the fate of Cadet Suttons father, a soldier killed in the first Battle of the Somme. With quiet compassion the lieutenant had demonstrated his discernment of the devastation the tortures the cadets mother must have endured. How does a young widow cope with such circumstances? Alan, I have something to tell you... How do you explain to a boy of just four years about the loss of his father, a man they had revered, the man on whom so much depended?

Look! one of the crew members yells and points upwards. His reminiscences disrupted, Midshipman Sutton observes the restlessness of the gulls and he sees how their agitation is heightened when the boat nears the shoreline. His eyes narrow as he squints up at the birds. He discerns their impatient flutter against the backdrop of fractured stratus and he notices how occasional breaks in the cloud reveal the first of the stars, the brightest of the stars. What was he told at school? He remembers the teacher at the Christs Hospital School, Horsham, who tried to explain about the muses: about Zeus and Mnemosyne; about their nine daughters. So which, then, was the muse of astronomy? Urania? Yes, that was it: Urania. He gazes at the heavens for some seconds; the stars in Scottish skies seem to have added clarity.

A determined gull looks aggressive, uncommonly so, as it squawks and swoops towards the picket boat; the midshipman feels an instinctive desire to duck. He must be getting edgy. He glances back at his mother vessel, HMS Repulse , a battle-cruiser at anchor in the outer reaches of the Cromarty Firth. He makes out the profile of the ship, the funnels and bridge structure, the guns fore and aft, the elegant line of the hull, how this disguises the mass of the 32,000 ton displacement. The Repulse , the twelfth Royal Navy ship to bear the name since first used in 1595, was built by the Clyde company of John Brown and was completed in August 1916. The ship, which is now farthest from his present position, is anchored off the town of Cromarty. He notes how the other ships are secured systematically in pairs until, between Invergordon and Udale Bay, HMS Hood and Rodney are set apart on their moorings.

He spots the navigation lights of the Repulse , then he checks around him to observe the lights of the whole fleet. He sees the sparkle of an Aldis communications lamp come to life; the operator winks some message to a fellow rating. He feels awed as he gazes at the grandeur of the largest of the ships within His Majestys Atlantic Fleet; at present, the smaller craft are moored off Rosyth in the Firth of Forth. In the next day or so these elements are due to sail north to take part in the fleets autumn exercises.

Despite the size and the splendour of the fifteen or so warships now in view, the midshipman realizes that the vessels become harder to make out in this fading light of dusk. He contemplates how the grey outlines seem deceptive: the exteriors disguise hives of activity within; the ships teem with an urgent and remarkable vitality. So many disciplines are contained within the depths of those hulls: engineers, gunners, administrators, marines, caterers... the cooks seem to work miracles under such conditions. He shivers again, and he wonders what will be on the menu in the midshipmens mess tonight.

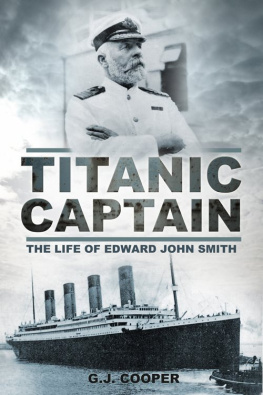

Not that he feels hungry at this moment; his sense of anxiety sees to that. The food, though, will be enjoyed eventually. At least the navy attempts to look after its people in that respect. The task must be Herculean; the numbers enormous. The Repulse s crew is newly commissioned, and when gathered for arrival briefings he and his fellow midshipmen were told specifics about the ships organization. Details of domestic requirements were explained: the complexity of arrangements to feed the ships crew of 1,181 personnel. He remembers the conversations that followed: the midshipmens incredulity at the figures; the subsequent discussions and the comparisons, so revealing, between naval rations and the now-famed provisions taken onto the liner Titanic ... 75,000 lb of fresh meat, 40,000 fresh eggs, 1,500 gal of milk, 11,000 lb of fresh fish, even fifty boxes of grapefruit. The officers laughed; such luxury was unlikely to become part of a naval diet.