Books published by The Random House Publishing Group are available at quantity discounts on bulk purchases for premium, educational, fund-raising, and special sales use. For details, please call 1-800-733-3000.

In each ship there is one man who, in the hour of emergency or peril at sea, can turn to no other man. There is one who alone is ultimately responsible for the sage navigation, engineering performance, accurate gunfire, and morale of his ship. He is the Commanding Officer. He is the ship!

Introduction

The United States Submarine Force in World War II was known as the Silent Service because the heroic deeds of submariners were kept secret. This slender force, with only 1.6 percent of the total personnel of the U.S. Navy, sunk fully 55 percent of the 10 million tons of Japanese warships and merchantment accounted for by Allied sea and air armadas.

The price of this remarkable success was shatteringly high. Fifty-two boats were lost; 22 percent of submarine crewmen died in action. Their ships became their steel coffins. This was the highest fatality rate of any branch of the U.S. Armed Forces.

Seven submariners won the Medal of Honor, the nations highest decoration for valor. Thirty-seven submarines were awarded the elite Presidential Unit Citation; another thirtysix boats were recipients of the slightly lesser Navy Unit Commendationby far the highest ratio of any class of warship.

To achieve this shining record, young submarine skippers overcame outdated peacetime tactics, weaknesses in command strategy, and defective weapons. The failure of U.S. torpedoes to function properly amounted to a secret wartime scandal, bordering on the criminal. Flawed torpedoes cost many submariners livesand needlessly prolonged the war against Japan. Despite all adversity, the skippers left a valiant legacy to the captains of todays huge, nuclear, ballistic boats: not since World War II has an American submarine fired a torpedo in combat. Only 465 officers commanded the U.S. submarines that went on 1,682 war patrols in World War II. Some failed. More succeeded. Many died.

Of the gallant conduct of this Nelsonian band of brothers, Captain Edward L. Beach, who was one of them, noted: World War Two saw the last of the old species of naval warfare in which the fate of nations hung on the ability of a few fearless men to rise above the shocking disruption of mind, and terror of painful annihilation by drowning, suffocation, burning or scalding to do their duty in spite of it all.

This is the story of Richard OKane, Americas undersea ace of aces, and a few fearless men, submariners all.

CHAPTER ONE

Wahoo Is Expendable

At the first, pale light on a January morning in 1943, Wahoo carved through the calm waters of the South Pacific with her crew at full alert. In the breaking, shimmering dawn, the sleek, matte-black American submarine strained on the surface at full speed, 18 knots, her powerful diesel engines leaving a boiling wake astern. Wahoo was approaching the Vitiaz Strait, a narrow waterway separating the Solomon Sea from the Bismarck Sea off the northeast coast of the big island of New Guinea. The strait was a maritime chokepoint, patrolled by Japanese aircraft and anti-submarine vessels from nearby New Britain Islanddangerous water for U.S. submarines.

Wahoos seventy-one crewmembers shared an edgy expectancy. They were embarked on a war patrol to seek out armed, enemy ships. They would be risking all. Thousands of miles from a friendly port, they would face the enemy alone. Defeat would mean death in their own iron coffin, in a nameless deep. They were heading into a no mans sea, and Wahoo was fair game for foe, or even friendpatrol planes from Australia had a nasty habit of dropping bombs on American submarines. Normal doctrine called for Wahoo to dive beneath the surface at first light and proceed submerged. But the situation was not normal. Wahoo was holding to a breakneck pace to reach a Japanese-occupied harbor, and running on the surface would save precious hours.

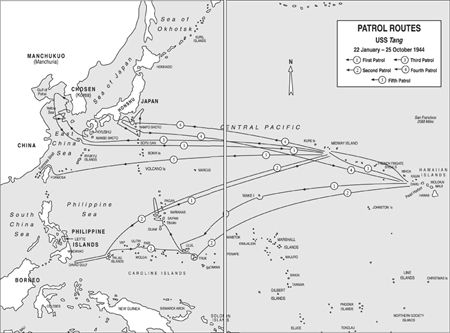

Now, seven days out of the U.S. Submarine Base at Brisbane, Australia, Wahoo was several hours ahead of schedule heading for her patrol area around the Japanese-held Palau Islands east of the Philippines. En route to her assigned area, Wahoo had orders to make a slight detour, if possible, to reconnoiter the anchorage of Wewak on the north coast of New Guinea, captured by the Japanese in the conquest of the East Indies the year before. It was used by the Japanese as a staging area to support amphibious operations in the Solomon Islands chain. Thanks to her four powerful diesel engines Wahoo was able to maintain an 18-knot speed, almost 21 statute miles per hour. (A knot, a nautical mile per hour, is 1.15 statute miles an hour.) To fit in the requested reconnaissance, Wahoo was running at full speed on the surface despite the proximity of Japanese airfields. Submerged on batteries, her speed would have been reduced to 5 or 6 knots at best.

Though crewmembers were apprehensive, they were curiously confident. For Wahoo on her third war patrol was commanded by two officers whom they trusted, and whose leadership was soon to become famous throughout the U.S. Submarine Force. The sense of confidence was pointedly shared by the executive officer, Lieutenant Richard OKane, a handsome 31-year-old sailor with light-brown almost rusty hair, a strong jaw, firm set to his mouth, and an open face. Dick OKane was of medium height and in fine physical condition. A New England Yankee, OKane was energetic and outgoing, but sometimes sharp-tongued. His temperament was changeable, the crew thought. He could be voluble, or he could be quiet. The XO seemed by turns charming or curt, warm or irascible. But whatever his mood, he had a reputation as a hard-charger.

OKane put Wahoo into commission on June 15, 1942, as executive officer under then skipper, Commander Marvin Kennedy. OKane was delighted with the vessels name. U.S. fleet boats were named after marine life and a wahoo is a large, swift, game fish. But Wahoo sounded to OKane and the crew like the name of an Indian tribe. So her battle flag pictured an American Indian headdress.

Despite Wahoos early promise and well-trained crew, OKane, the number two, was frustrated at Captain Kennedys performance as skipper on the first two Pacific war patrols. He believed Kennedy was not aggressive enough, and failed to press attacks against choice enemy targets, including an aircraft carrier. Dick OKane decided he would not make a third war patrol under Marvin Kennedy. He would ask for a transfer off Wahoo.

OKanes unstated feelings were shared by the enlisted men and other officers, and that mood translated into ragged morale among the crewmen, who were all volunteers prepared to risk their lives on patrol. Wahoo, with only one confirmed enemy ship sunk, had not made much of a record. Captain Kennedy may have had his excuses, but the crew did not want excuses. They wanted a good record. They wanted to sink enemy ships.

What buoyed the morale of Dick OKane and