I would like to thank the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, Nova Scotia Archives, Dalhousie University, Halifax Public Libraries, Fisheries Museum of the Atlantic, Dartmouth Heritage Museum, Age of Sail Heritage Museum (Port Greville, NS), United Empire Loyalists Association, British Consulate, Frank and Heather Johnson, Capt. Robert Cormier, Valerie Lenethen, Dan Conlin, Allison Lawlor, Dennis Macormick, Geoff Frampton, Gavin Will, Stephanie Porter, Iona Bulgin, and, as usual, those I have forgotten.

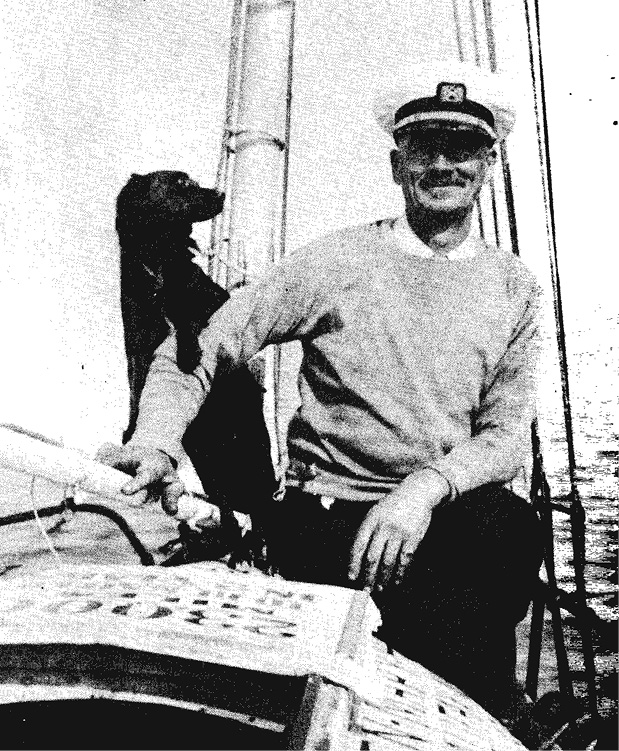

Capt. Crowell and Togo on the Queen Mary.

CHILDHOOD

I will go back to my childhood days and the cottage, the home of my father. During the last years of my grandfathers life, he spent several winters in our small home. I remember his chair in the kitchen, the Waterloo stove, the stories he told, and the songs he sang. How I loved that grand man of the sea. As I grew up, between the ages of five and 12, he would stroll with me across the fields or by the lake shore or accompany me out in the boat with a fishing line.

So gentle were his waysso different from the many seagoing types that I joined in later years. Till he retired, he spent his life on the decks of large square-rigged ships. The decks of these ships were his home; he had no other.

Oh, how I recall that voice again

The one I loved so dear,

I knew no one so good and true

With him I had no fear.

As I strolled with him through trees or field,

Sometimes upon his arm,

He taught me prayers, he sang me songs,

He told me right from wrong.

He said to me, You are my boy,

My ship and all its stores,

And that old sea chest that has long been mine,

Someday it will be yours.

My dear grandfather, his sea chest, his sea stories, and his songs live in my memory. He would open up that chest and go over everything, the many beautiful things, and fold them and place them carefully back in the box after telling us about them. Looking inside the box, Id see a ship in a bottle, a lighthouse, and water paintings decorating the four sides of the box. On the inside cover was a painting of a small square-rigged ship called The Golden Gate. How real it looked, with her British flag and her numbers in flags. With his trembling hand, my grandfather would add pictures of ships under sail and at anchor on the boxs cover. He must have been an artist of no mean ability in his early life.

During the winter of my 14th year my grandfather became confined to the house, and in early May I became heir to that chest and his belongings. Under his pillow was a letter addressed to My Dear Boy. I did not have to open it to know it was mine.

Oh, could I lock this worried mind

And find my past untrue,

And wake up in the early morning,

And start the day anew.

My grandmothermy fathers motherhad incredible strength and an equally incredible temper. At age 50 she fell from an ox cart, and the wheel went over her body and fractured her hip. For two years, she was unable to walk and, afterward, she walked with a stick. But she weathered the gale and, for 45 more years, visited the neighbourhood as a midwife, paying six visits to our home.

I remember her visits; she would arrive at our home by ox cart or horse and sleigh, according to the season. She was not very friendly to me or to any of the family. She had the voice of a bull moose and the temper of an evil spirit. Our family was always glad to see her return home. My father was a very gentle and mild man, and I often wondered how he could be so different from his mother.

Our little cottage was by the side of a lake where I learned to fish, row, and swim. One day, when I was four years old, neighbours gave me a little black and tan pup, which I named Frisk. As he grew older, Frisk followed me everywhere. For the 13 years he lived, he was all mine. Our barnyard stock consisted of a pig, a few hens, an ox, a cow, and Frisk. If I remember rightly, we once had four sheep too. Food was hard to get and meals were not regular. On the days my grandmother was with us she did the work around the house, with the help of my eldest sister. She looked after the straining of the milk and churned on Saturday mornings. The churn had a hand plunger.

I was perhaps eight years old on my grandmothers last visit. On that particular Saturday morning she had poured the cream into the churn, but had left it to go out to the clothesline. The churn was open, so Cliff, my brother, and I thought we would sample a few spoonfuls while her back was turned. Frisk jumped up on the table to be near me. When we heard my grandmothers stick on the porch, we made a clean getaway. Frisk was not so fortunate. Somehow he got turned around, head-up, his nose just out of the churn and as pretty a cream colour as could be. We feared something terrible might happen to him, but my grandmother simply plucked him out of the churn, and he made a quick retreat. That was not the end, howeverI was the one upon whom she wreaked her anger.

Outside the house were several bundles of rods which my father had been using to make eel-pots. Grandma took one of these rods, made a quick grab for me, and gave me the most terrible whacking. When I finally escaped, I ran to my mother, who was lying in bed, full with child. She took me in her arms and soothed me as best she could. That night she gave birth to her seventh child, a boy, who was stillborn. This tragedy cast a gloom over the entire household. A week or so later Mother resumed her household chores and, from then on, my grandmother was forbidden to enter our home again. She passed away in her 95th year.

Between the ages of six and 16, my school days were few and far betweenperhaps a couple of days a weekand my grading ended with the fourth book and, of course, addition and subtraction, but I have had many hard lessons since my school days. I was healthy and strong, but small, weighing only 100 pounds at age 13. In later years I started to grow and at 22 was 6 feet tall and weighed 184 pounds. But I had plenty of inner strengthwhat it takes to make an iron man who would sail the high seas in wooden ships.

One cold morning in November, the lake beside the little red schoolhouse had risen high from a weeks rain. The water was very deep, but with the heavy north wind the lake had started to freeze. We had a slide down the steep bank onto the lake, and on this particular morning the water had frozen enough to bear a mans weight for perhaps 50 feet. Beyond that was thin ice and open water. Most of the schools 20 children had gathered before the morning bell rang to slide out on the ice, the first of the season.

Charlie Hoskins was perhaps six years old, strong and bright for his age. The children had made many slides before I arrived. I was coming along the shore and around the turn, perhaps a quarter of a mile from them, when Charlie made his last slide. A gust of wind caught him and pushed him toward the edge of the thin ice. He sat down, broke through, and disappeared. The children screamed. I saw what had happened and ran for the place he had gone through. I had learned to swim and dive.

Charlie came up, his head out and his hand on the ice, but before I could reach him, he went down again. I reached the hole and, without a thought, I went in. My feet struck his little body. I reached down and pulled him to the surface. With my best efforts I could only shimmy him partly out. His head and breast lay on the thin ice and the quick frost froze his coat sleeve fast in a few seconds. I saw I had no chance. Just when I had about lost hope, Neil McGinnis, who had heard the childrens screams from his barn, came running, tearing a pole from the fence as he ran. He shoved it out to me. I had trembling hands and a chilled body but enough strength left to grab the pole. When McGinnis pulled me out, I grabbed Charlie, and they hauled us to the shore. We were both in bad condition.