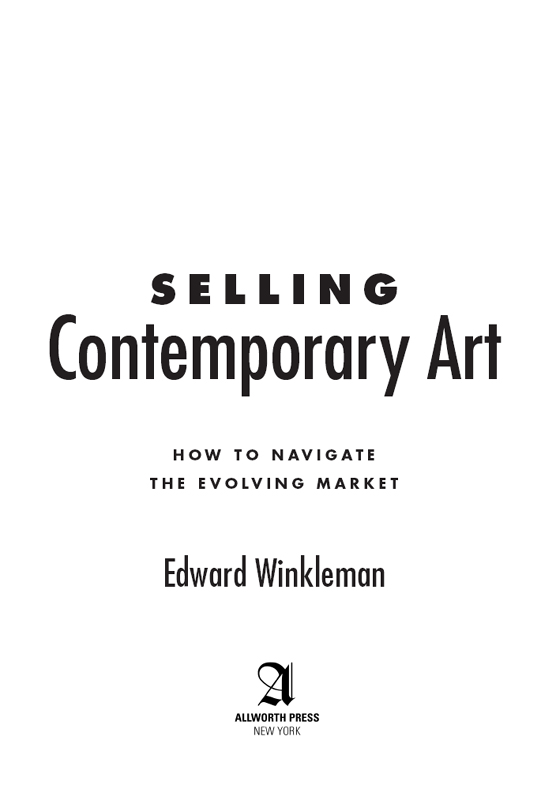

Copyright 2015 by Edward Winkleman

All rights reserved. Copyright under Berne Copyright Convention, Universal Copyright Convention, and Pan American Copyright Convention. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Allworth Press, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Allworth Press books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Allworth Press, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

19 18 17 16 15 5 4 3 2 1

Published by Allworth Press, an imprint of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.

307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Allworth Press is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

www.allworth.com

Cover design by Mary Belibasakis

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Print ISBN: 978-1-62153-462-4

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-62153-473-0

Printed in the United States of America.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

The Leo Castelli Model

I n late 2008, just as I was finishing my book How to Start and Run a Commercial Art Gallery, it felt like someone he had turned off the spigots of the contemporary art market all at once. One day we were wheeling and dealing as normal, despite distant rumblings of a worldwide economic meltdown, and seemingly the next day everyone stopped returning phone calls or emails. People stopped going to the galleries as well. It all seemed so sudden, at least for the generation of younger art dealers who, having opened their galleries in the twenty-first century, had never known anything but boom times.

News of giant corporations and financial institutions going belly-up came on a regular basis. Many of them had been good, steady collectors. If these masters of the universe couldnt navigate the economic turmoil, what chance did mom-and-pop-style galleries stand? Smaller galleries in particular were nervous. Tales of 40 percent discounts being offered by top-level galleries to close deals sent chills through the community. How could we survive on that? Then the galleries started closing too. Not as many as people had predicted, perhaps, but enough to make those dealers still open begin to search for new ways to conduct business.

Many new models were floated and discussed, including that dealers should follow the example set by fashion designers and merge under an umbrella corporation, such as the luxury brands conglomerate LVMH. And while the advocates of such a model were definitely onto something, they mistook the parallel as being between fashion designers and art dealers, when it actually turned out to be between fashion designers and visual artists themselves. Indeed, if the Great Recession (as the economic downturn has come to be called) issued any bold new practices into the contemporary art market, the open marketing of a visual artist by a conglomerate, or mega-gallery, as a brand would be high on the list. What I mean by that specifically is the shift from marketing individual art objects based on their quality to the marketing of any object made by a high-profile artist based on their name and demand for their work.

Granted, a more subtle branding of artists themselves had been a conscious part of marketing contemporary art for many decades, at least since 1960, when legendary art dealer Leo Castelli (19071999) managed to sell a sculpture of two beer cans by his then rising star artist Jasper Johns. But late 2008 saw a giant leap forward in a more direct approach to that practice. In the years that followed, this more blatant branding of artists over artworks, combined with an emphasis on expanding the power and even real estate of the conglomerate, would impact nearly every aspect of the contemporary art market, including how feasible it remained to run a gallery in what has become known as The Leo Castelli Model.

In a nutshell, Mr. Castellis model was to discover the best artists he could, nurture their careers, carefully guide their markets (especially by not pushing their prices too high too quickly), all with the intention of growing old and successful together in a mutually agreeable partnership. The specifics of this model include taking work on consignment (rather than buying it and reselling it, as retailers do in most other industries) and paying artists a percentage of any sales, typically in a 50/50 split; representing the artist such that they were expected to only sell through the gallery in return for sustained promotion and regularly scheduled exhibitions; and managing many of the more mundane aspects of their career, including handling logistics for museum or other gallery exhibitions, archiving their press and images of their work, and many other tasks artists would rather someone else free them from doing so they could focus on creating their work.

Leo Castelli did not invent many of the strategies behind his unparalleled success at selling contemporary art (and in reality, even he was not as consistent in such matters as legend has it), but he optimized a series of best practices for art dealing in a way that was so admired by artists and younger dealers alike that it unofficially became the way its done. The cornerstone of the model was for mutual trust and loyalty between dealer and artist to guide what was presumed to be a long-term relationship over the inevitable ups and downs of both an art career and the economys cycles. Indeed, it was this presumption that artist and dealer were not only a team, but that they would remain so for many years, that made an early heavy investment by the art dealer in the relatively unknown artist more sensible from a business point of view.

Again, even Leo Castelli didnt follow those best practices to the letter, but by 2008, when artist Damien Hirst, one of the biggest brands in the contemporary art world, cut out his powerful New York and London galleries by bringing a huge body of his work direct to auction, few could any longer claim the Castelli model was the only path to success. This book is an attempt to summarize the changes in the contemporary art market since 2008, with a particular focus on the challenges and innovations just now entering the market. It explores a number of shifting factors, and is based on a wide range of interviews with collectors, dealers, artists, fair organizers, and other art world entrepreneurs, with the ultimate goal of helping anyone attempting to sell contemporary art strategize on how to navigate the quickly evolving market.

then explores the strategies that galleries use, or might use, to more effectively navigate these areas of change.

looks at specific areas of change that dealers themselves are initiating. In other words, things that dealers are doing differently to respond to outside forces or simply evolve with the times. Again, much of what is discussed in this part is likely to continue to evolve, and so each chapter also attempts to synthesize the collective wisdom of the art sellers interviewed in them to predict how these areas of change might play themselves out.

of the book, co-authored by the art attorney (and my friend) M. Franklin Boyd, Esq., reflects an opinion held by more and more dealers, as well as many collectors of contemporary art: that as the market grows in size, the handshake way of doing business will increasingly need to give way to contracts. Some of the basics behind these contracts are discussed in my first book. New considerations in response to things that have changed since that time are outlined in the chapters dealing with Representation and Consignment contracts. Considerations not covered in the first book, such as contracts for new forms of art that have or may come along, are then discussed in later chapters.