The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Emma Louise Page

Im not a great admirer of the sea. Theres too much of it from my point of view.

M AURICE O LIVER , lighthouse keeper

CONTENTS

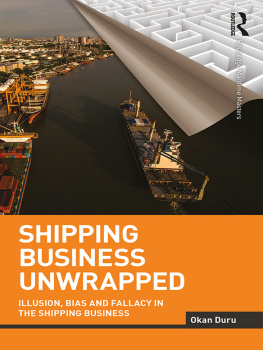

Maersk Kendal, three football pitches long

(ROSE GEORGE)

INTRODUCTION

Friday. No sensible sailor goes to sea on the day of the Crucifixion or the journey will be followed by ill-will and malice. So here I am on a Friday in June, looking up at a giant ship that will carry me from this southern English port of Felixstowe to Singapore, for five weeks and 9,288 nautical miles through the pillars of Hercules, pirate waters, and weather. I stop at the bottom of the ships gangway, waiting for an escort and stilled and awed by the immensity of this thing, much of her the color of a summer-day sky, so blue; her bottom is painted dull red, her name Maersk Kendal written large on her side.

There is such busyness around me. Everything in a modern container port is enormous, overwhelming, crushing. Kendal, of course, but also the thundering trucks, the giant boxes in many colors, the massive gantry cranes that straddle the quay, reaching up ten stories and over to ships that stretch three football pitches in length. There are hardly any humans to be seen. When the journalist Henry Mayhew visited Londons docks in 1849, he found decayed and bankrupt master butchers, master bakers, publicans, grocers, old soldiers, old sailors, Polish refugees, broken-down gentlemen, discharged lawyers clerks, suspended Government clerks, almsmen, pensioners, servants, thieves. They have long since gone. This is a Terminator terminal, a place where humans are hidden in crane or truck cabs, where everything is clamorous machines.

It took me three train journeys to reach Felixstowe from my northern English home. On one train, where no seats were to be had, I swayed in the vestibule with two men wearing the uniform of a rail freight company. Im about to leave on a freighter, I said, but a ship. They looked bewildered. A ship? they said. Why on earth do you want to go to sea?

Why on earth.

I am an islander who has never been maritime. I dont sail or dive. I swim, although not in terrifying oceans. But standing here in the noise and industry, looking up almost two hundred feethigher than Niagara Fallsto the top of Kendal , I feel the giddiness of a Christmas morning child. Some of this is the rush of escape, for which I had reasons. Some is the pull of the sea. And some comes from the knowledge that I am about to embark to a place and space that is usually off-limits and hidden. The public is not allowed on a ship like this, nor even on the dock. There are no ordinary citizens to witness the workings of an industry that is one of the most fundamental to their daily existence. These ships and boxes belong to a business that feeds, clothes, warms, and supplies us. They have fueled if not created globalization. They are the reason behind your cheap T-shirt and reasonably priced television. But who looks behind a television now and sees the ship that brought it? Who cares about the men who steered your breakfast cereal through winter storms? How ironic that the more ships have grown in size and consequence, the less space they take up in our imagination.

The Maritime Foundation, a charity that promotes seafarer matters, recently made a video called Unreported Ocean . It asked the residents of Southampton, a port city in England, how many goods are transported by sea. The answers were varied but uniformly wrong. They all had the interrogative upswing of the unsure.

Thirty-five percent?

Not a lot?

The answer is, nearly everything. Sometimes on trains I play a numbers game. A woman listening to headphones: 8. A man reading a book: 15. The child in the stroller: at least 4 including the stroller. The game is to reckon how many of our clothes and possessions and food products have been transported by ship. The beads around the womans neck; the mans iPhone and Japanese-made headphones. Her Sri Lankamade skirt and blouse; his printed-in-China book. I can always go wider, deeper, and in any direction. The fabric of the seats. The rolling stock. The fuel powering the train. The conductors uniform; the coffee in my cup; the fruit in my bag. Definitely the fruit, so frequently shipped in refrigerated containers that it has been given its own temperature. Two degrees Celsius is chill but 13 degrees is banana.

Trade carried by sea has grown fourfold since 1970 and is still growing. In 2011, the 360 commercial ports of the United States took in international goods worth $1.73 trillion, or eighty times the value of all U.S. trade in 1960. There are more than one hundred thousand ships at sea carrying all the solids, liquids, and gases that we need to live. Only six thousand are container vessels like Kendal , but they make up for this small proportion by their dizzying capacity. The biggest container ship can carry fifteen thousand boxes. It can hold 746 million bananas, one for every European on one ship. If the containers of Maersk alone were lined up, they would stretch eleven thousand miles or nearly halfway around the planet. If they were stacked instead, they would be fifteen hundred miles high, 7,530 Eiffel Towers. If Kendal discharged her containers onto trucks, the line of traffic would be sixty miles long.

Trade has always traveled and the world has always traded. Ours, though, is the era of extreme interdependence. Hardly any nation is now self-sufficient. In 2011, the United Kingdom shipped in half of its gas. The United States relies on ships to bring in two-thirds of its oil supplies. Every day, thirty-eight million tons of crude oil sets off by sea somewhere, although you may not notice it. As in Los Angeles, New York, and other port cities, London has moved its working docks out of the city, away from residents. Ships are bigger now and need deeper harbors, so they call at Newark or Tilbury or Felixstowe, not Liverpool or South Street. Security concerns have hidden ports further, behind barbed wire and badge wearing and KEEP OUT signs. To reach this quayside in Felixstowe, I had to pass through several gatekeepers and passport controllers, and past radiation-detecting gates often triggered by naturally radioactive cargo such as cat litter and broccoli.

It is harder to wander into the world of shipping, now, so people dont. The chief of the British navywho is known as the First Sea Lord, although the army chief is not a Land Lordsays we suffer from sea blindness now. We travel by cheap flights, not ocean liners. The sea is a distance to be flown over, a downward backdrop between takeoff and landing, a blue expanse that soothes on the moving flight map as the plane jerks over it. It is for leisure and beaches and fish and chips, not for use or work. Perhaps we believe that everything travels by air, or magically and instantaneously like information (which is actually anchored by cables on the seabed), not by hefty ships that travel more slowly than senior citizens drive.

You could trace the flight of the ocean from our consciousness in the pages of great newspapers. Fifty years ago, the shipping news was news. Cargo departures were reported daily. Now the most necessary business on the planet has mostly been shunted into the pages of specialized trade papers such as Lloyds List and the Journal of Commerce , fine publications but out of the reach of most, when an annual subscription to Lloyds List costs more than $2,000 a year. In 1965, shipping was so central to daily life in London that when Winston Churchills funeral barge left Tower Pier to travel up the Thames, it embarked in front of dock cranes that dipped their jibs, movingly, with respect. The cranes are gone now or immobile, garden furniture for wharves that house costly apartments or indifferent restaurants.