Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To the National Health Service

Blood makes me feel so much better, and once Ive had blood I want to play with my toys again.

Owen Porter, 10

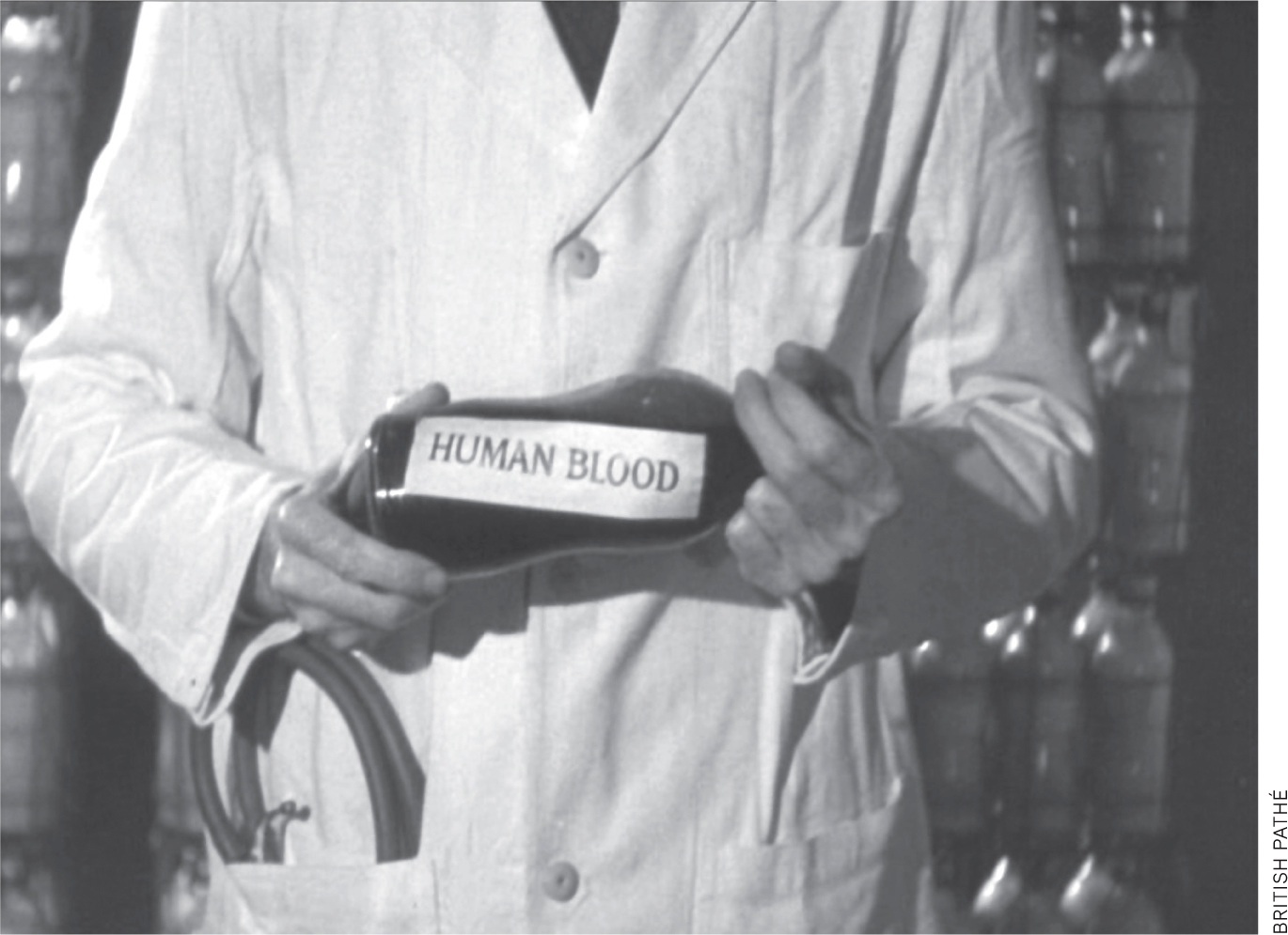

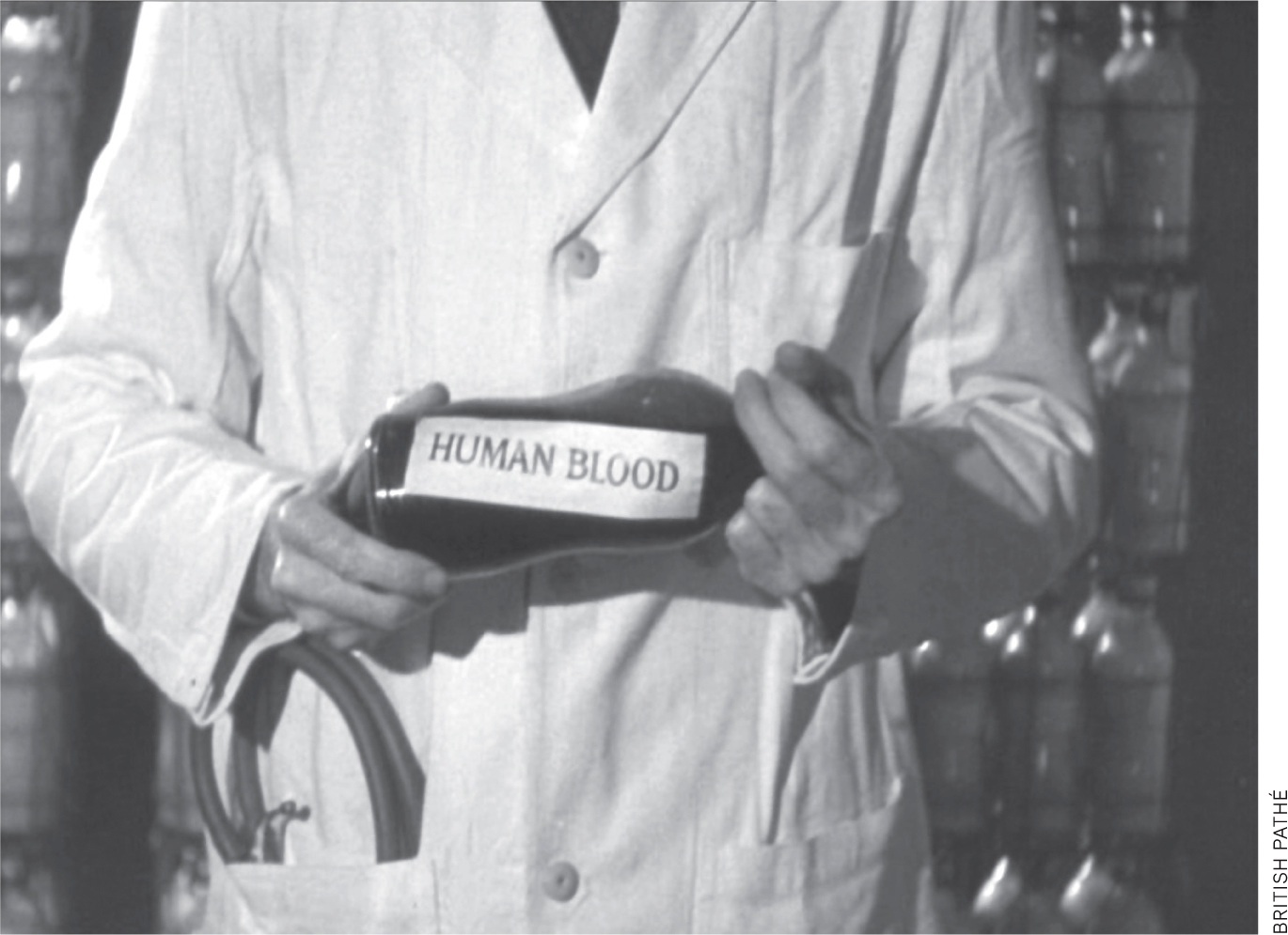

Ministry of Information trailer promoting blood donation, 1946

There is a TV but I watch my blood. It travels from a needle stuck in the crook of my right elbow, the arm with better veins, into a tube, down into the clear bag that is being hugged by a cradle that rocks then jerks, agitating its contents, stopping the clotting. Rock and wiggle. Rock, then wiggle.

I am giving away almost a pint, and it feels like it always does: soothing and calming. I watch the bag fill with this red rich liquid, which amounts to 13 percent of my blood supply.

People have different rates of flow so the machine beeps with alarm when the output is too low. Today mine has been acceptable. Once, my veins were judged too small and I was turned away by the National Health Service Blood and Transplant (NHSBT), and I was insulted as if the rejection were moral, not medical. For a material that has been studied for thousands of years, blood still manages to run from rationality, even at walking pace.

Donating doesnt take long. Im done in ten minutes. Female, A pos, time bled 11 a.m. Now Im due to get thanked. Gratitude is the main theme here: the Wi-Fi password is thank you. This is the main donor center in Leeds, my hometown and a city of three quarters of a million people. A bright, well-staffed place on one of the biggest shopping streets. Over the road at Red Hot restaurant, you can buy all you can eat from any cuisine in the world, all at once. One hundred dishes. Here, you can lie back and do not muchthough clenching your buttocks helps keep your blood movingand help three people, all at once. Give blood, and your donation can be separated by NHSBT, the public health agency that operates blood and organ transplant in England and Wales, into several lifesaving, life-enhancing gifts. By gifts they mean components such as red blood cells, platelets, plasma, and other useful fractions. Such details are available in NHSBT literature, as are phrases like date bled. In the early days of the blood service, there were bleeding couches. But now the straightforward language of biology has changed to one of altruism. Its all donation and gift. The reality of it, that I am emitting a bodily fluid in public, is contained as much as possible, and not just in clear plastic bags.

Once decanted into its container, my blood is on its way to becoming something that even when given for free can be brokered and sold like ingots or wheat. It is also immediately much more perishable than it was in my veins: even when mixed with a storage medium, red blood cells have an official shelf life of between thirty-five and forty-nine days, depending on local laws. They last longer than milk but not as long as cheese. This fragile but powerful substance can become a medicine, a lifesaver, and a commodity that is dearer than oil. Yet I give my blood freely because I know that my body will soon replace it and other people need it. I want nothing in return but a mint biscuit, a cup of tea, and a sticker that reads BE NICE TO ME. I GAVE BLOOD TODAY .

* * *

Every three seconds, somewhere in the world, a person receives a strangers blood. Globally, 13,282 centers in 176 countries collect 110 million donations. The United States transfuses 16 million units of blood annually; the UK, 2.5 million. All of this blood is given to people when they have cancer or anemia or when they give birth; it can assist equally in trauma or chronic disease. Some accident victims can receive 60 units of blood; a liver transplant patient can use 100, or several bodies-full. A newborn can be saved with a teaspoonful. Read about the modern use of blood, and the word precious or special will appear alongside health care resource . Economists call the sale of organs and body parts a repugnant market. But blood is different. The movement of blooda body part, after allis accepted unquestioned and common enough to be banal. But it is wondrous, still. It is as wondrous as blood.

Poor Odysseus. Deep in Hades, surrounded by ghosts and wraiths, and his mother wont speak to him. Not until she drinks the blood that Odysseus has taken from reluctant sheep. For Homer, blood had a power as fierce and invisible as electricity: a mouthful of blood, a switch flicked, and Anticlea could now speak to her son. This bright red liquidbrighter in the arteries, when it is transporting oxygen around the body from the heart, duller in the veins, when it is notcontains salt and water, like the sea we possibly came from.

We no longer sacrifice humans or beasts but the force of blood remains in language: blood feud, blood brothers, bloodlines. It remains in metaphor, where blood becomes an emotional state: my blood can be chilled, boiling, curdled. And its force remains in reality: most people associate the cheating cyclist Lance Armstrong with his abuse of erythropoietin (EPO), a hormone that stimulates the body to make more red blood cells. But I cant shake the image of him with a fridge full of his own blood, removed from his own body and ready to be transfused back into it.

The mythical Gorgon Medusa, with her head of snakes, showed the two-faced nature of blood best: the veins on her left side contained blood that was lethal, while the right side gave life. Transfusions can be two-faced, too. The right type of blood can save your life; the wrong one can kill you. I am calmed by the sight of my blood when it is being drawn or when I scratch it out from under my skin. I also curse it: along with stray menstrual tissue, it has wandered around my body for years to where it shouldnt be, so that I am riddled and glued by the adhesions of endometriosis, and every month they bleed too, in cacophonous sympathy.

We fear blood, still, despite our science and understanding, and we look to blood to tell us who we should fear. In 1144, the death of a young man named William of Norwich was attributed to Jews who had crucified him in order to use his blood as a sacrifice. This was the first documented case of what became known as blood libel, and it was enduring and lethal: for centuries, blood libel was used as a reason to massacre Jews and steal their property, across northern Europe, again and again. I consider modern bans of gay men donating bloodthe prohibitions are being relaxed now but persistand see fear, not science. People with HIV are still jailed for not disclosing their status to sexual partners, long after HIV has become treatable to the point where it is not contagious. Chlamydia and hepatitis, now more life-threatening or disabling, get no such sanction. Blood is what artists still use to shock, although increasingly the menstrual kind.

Examine my blood with the right tools, and it can reveal who I am and what I was and what may become of me. I set up an alert to gather any mention of a simple blood test, and it brings me news that my blood can be tested to show my biological or chronological age; whether I am likely to develop Alzheimers, Parkinsons, or various types of cancer; whether surgery will give me delirium; whether my heart is failing; whether I am concussed. Most of these tests are still possibility and hope, or years away from being available. But already blood is a surveillance camera, the widest window with the best view into my past, present, and predictable future. Blood is one of the three main diagnostic tools of a doctor: the others are imaging and a physical exam.