Copyright by the University of Michigan 2011

All rights reserved

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher.

Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press

Manufactured in the United States of America

Printed on acid-free paper

Printed on acid-free paper

2014 2013 2012 2011 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Dierkes-Thrun, Petra, 1968

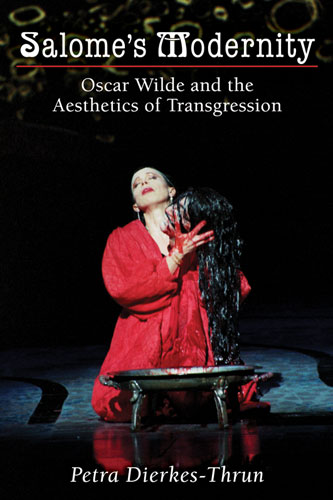

Salome's modernity : Oscar Wilde and the aesthetics of transgression / Petra Dierkes-Thrun.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-472-11767-3 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-472-02754-5 (ebk.)

1. Wilde, Oscar, 18541900. Salom. 2. Wilde, Oscar, 18541900Influence. 3. Salome (Biblical figure)In literature. 4. Deviant behavior in literature. 5. Modernism (Aesthetics) I. Title.

PR5820.S23D54 2011

822'.8dc22 2011000474

For Sebastian and Jasper, with love

Methinks my life is a twice-written scroll

Scrawled over on some boyish holiday

With idle songs for pipe and virelay

Which do but mar the secret of the whole.

Oscar Wilde, Hlas!

[P]hilosophy has been, up to this point, as much as science, an expression of human subordination, and when man seeks to represent himself, no longer as a moment of a homogeneous processof a necessary and pitiful processbut as a new laceration within a lacerated nature, it is no longer the leveling phraseology coming to him from the understanding that can help him: he can no longer recognize himself in the degrading chains of logic, but he recognizes himself, insteadnot with rage but in an ecstatic tormentin the virulence of his own phantasms.

Georges Bataille, The Pineal Eye

Acknowledgments

Salome's Modernity would not exist without the people who accompanied and nurtured it as mentors, colleagues, and friends over the years. It started as a dissertation in the English Department at the University of Pittsburgh, and to my teachers there, I owe my deepest intellectual debt. My heartfelt gratitude goes out to Paul A. Bov, who made the thinking and writing of this book possible through unfailing intellectual challenge and support. He has exemplified all the inspiration, trust, and skeptical rigor a true mentor and partner in critical dialogue can offer. Jonathan Arac, Lucy Fischer, and the late Eric O. Clarke served as committee members at the dissertation stage and spent much time talking and throwing around ideas about books, films, and feminist, queer, and critical theories with me in their offices and classrooms. They have been indispensable role models for me in countless ways throughout the years. Eric O. Clarke tragically passed away just a few months before this book was going to press, and I will miss him always. Philip E. Smith II supervised earlier stages of this project and published a pedagogical article of mine in his edition Approaches to Teaching the Works of Oscar Wilde (2008); I benefited greatly from his personal and professional support and deeply admire his scholarship on Wilde. Herbert S. Lindenberger (Stanford University) exhibited amazing energy, enthusiasm, and generosity in sharing his scholarly and pedagogical expertise and his love of opera with me, at the dissertation stage and ever since.

To Susan Teuteberg, Martina Gschell, Judy Suh, Eleni Anastasiou, Saeeda Hafiz, Beth Wightman, and Dorothy Clark, I say a special thank you for the best of friendship and shared love of people, books, and culture. David C. Rose, editor and founder of the Oscholars Web site and group ofjournals, gave me the opportunity to take charge of The Latchkey: Journal of New Woman Studies, and to expand my professional horizons in the realm of online publishing. As I was putting the finishing touches on Salome's Modernity, I was teaching a seminar at Stanford University entitled Salome, Modernity, Transgression, and I sincerely thank the students in that class for making the last stages of writing this book not only bearable but fun. One of them, the artist Dorian Katz, contributed an illustration to this book, for which I am especially grateful.

An earlier version of appeared in Modern Language Quarterly 69.3 (September 2008): 36789. For crucial institutional and financial support, I would like to acknowledge the Comparative Literature Department at Stanford University; the English Department and College of Humanities at California State University, Northridge; the English Department at Santa Clara University; the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation; the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at the University of Pittsburgh; and the German Catholic fellowship organization Cusanuswerk. For patient and helpful research support at various stages of the project, I am grateful to the staff at the William Andrews Clark Memorial Library (University of California, Los Angeles), the British Library, the Library of Congress, and the Theatermuseum Kln-Wahn, Germany. At the University of Michigan Press, my editor Tom Dwyer, editorial associate Alexa Ducsay, and managing editor Christina Milton were indispensable sources of support, and I thank them for their professionalism and enthusiasm in bringing this project to fruition.

Very special words of love and thanks go out to my family, especially to my husband, Sebastian Thrun, and our son, Jasper; my father, Rainer, and stepmother, Susanne Dierkes; and my brother, Sebastian, and his family. Without their unconditional love, unflagging support, and sense of humor, life could not be half as wonderful.

Introduction

Oscar Wilde's 1891 symbolist tragedy Salom has had a rich afterlife in literature, opera, dance, film, and popular culture. Even though the literature and art of the European fin de sicle produced many treatments of the famous biblical story of Salome and Saint John the Baptist, virtually every major version in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries has been some creative adaptation of or critical reaction against Wilde's Salom, with its infamous Dance of the Seven Veils and Saloms shocking final love monologue and kiss to the bloody, severed head of John the Baptist. For a work banned from the English stage by the theater censor before it was even produced, a play whose author remained intensely controversial for several decades after his notorious 1895 trials, this is a curious legacy. Why was it specifically Wilde's play, among the many provocative literary and artistic versions of the story of Salome, that proved so popular and fascinating? Why would Wilde's conception of a sexually anarchic, aestheticized Salom speak so importantly to artists and audiences of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries? What were the historical and cultural forces that established Wilde's Salom as a canonical text that, in turn, inspired more than a century's worth of creative cultural reinscriptions, adaptations, and transformations in many different genres and media? Finally, what can Western culture's ongoing fascination with figures like Salom and Wilde tell us about ourselves and about modernity? These are the some of the central questions Salome's Modernity sets out to answer.

In recent years, the bulk of Wilde's work has come into the purview of modernist studies, and Wilde is often discussed as a modernist as a matter of course, But Wilde developed and exacerbated his literary and artistic influences to a point that also marks a radical departure from his predecessors. Wilde's

![Wilde Oscar - The secret life of Oscar Wilde: [an intimate biography]](/uploads/posts/book/228457/thumbs/wilde-oscar-the-secret-life-of-oscar-wilde-an.jpg)

Printed on acid-free paper

Printed on acid-free paper