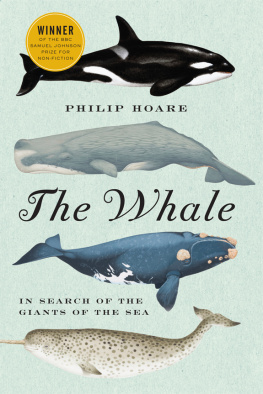

Also by Philip Hoare

Serious Pleasures: The Life of Stephen Tennant

Nol Coward: A Biography

In memory of Peter

Copyright 1997 by Philip Hoare

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

This Arcade Publishing paperback edition 2017

Arcade Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Arcade Publishing is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.arcadepub.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hoare, Philip.

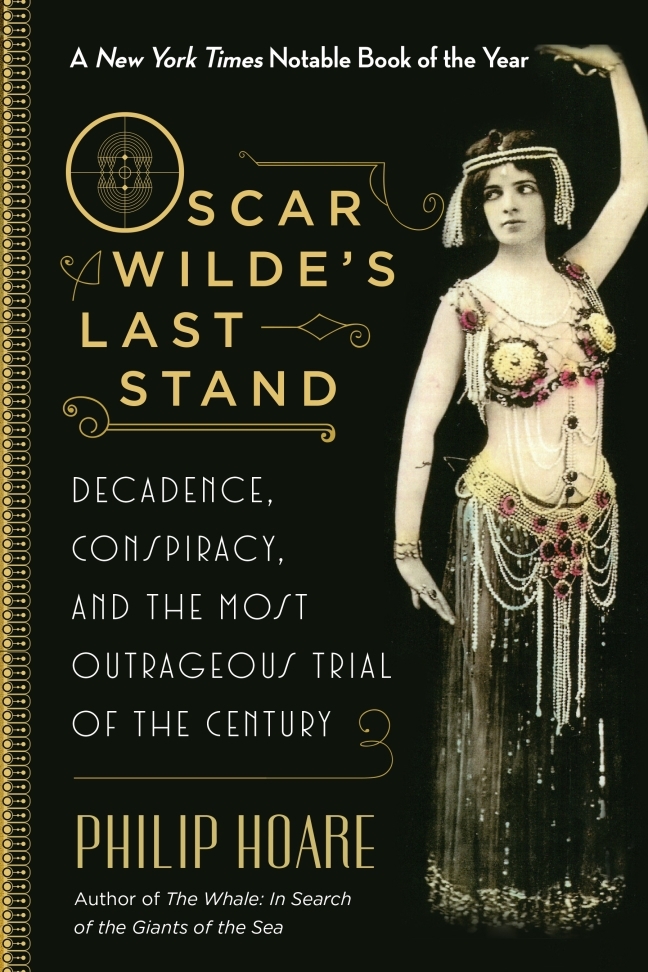

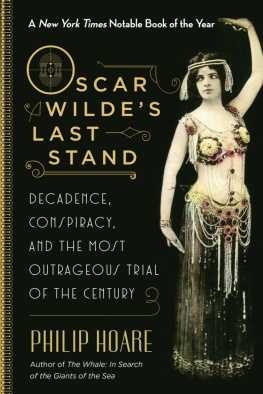

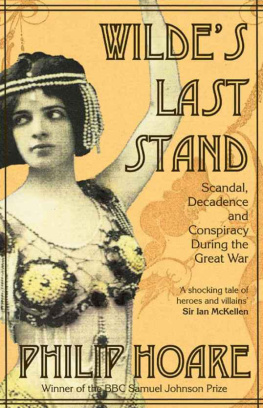

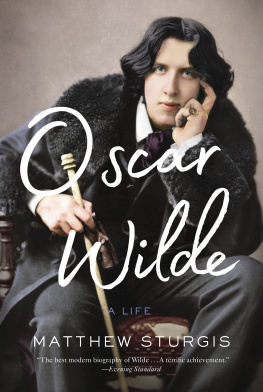

Title: Oscar wildes last stand : decadence, conspiracy, and the most outrageous trial of the century / Philip Hoare.

Description: New York : Arcade Publishing, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016048797 | ISBN 9781628726954 (paperback)

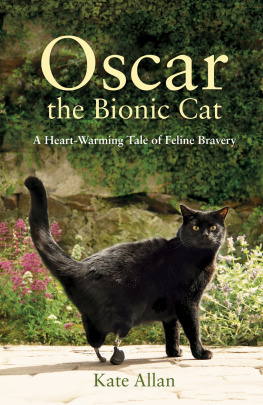

Subjects: LCSH: Billing, Noel Pemberton, 1881-1948--Trials, litigation, etc. | Trials (Libel)--England--London. | Allan, Maud. | Wilde, Oscar, 1854-1900. Salom?e. | BISAC: HISTORY / Europe / Great Britain. | PERFORMING ARTS / Theater / History & Criticism. | BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Entertainment & Performing Arts.

Classification: LCC KD373.B54 H63 2017 | DDC 346.4203/4--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016048797

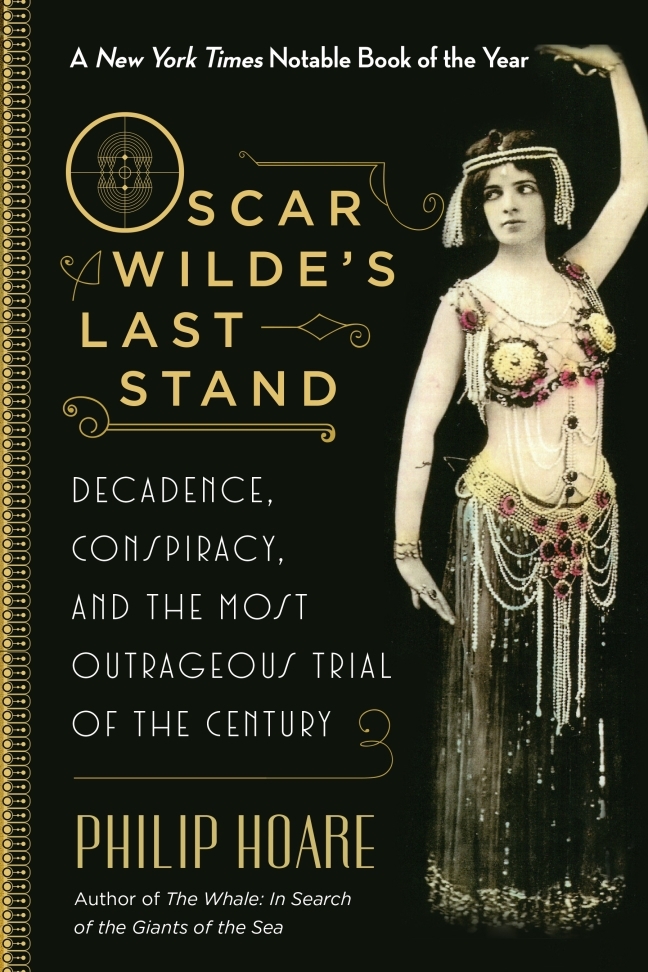

Cover design by Erin Seaward-Hiatt

Front cover image courtesy of Terence Pepper, National Portrait Gallery, and the author

Print ISBN: 978-1-62872-695-4

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-62872-763-0

Printed in the United States of America

Contents

Acknowledgements

It was in Paul Fussells ground-breaking cultural study, The Great War and Modern Memory , which I read when working on a biography of Stephen Tennant, that I first heard of the Billing trial. Tennant conducted a traumatic post-war affair with Siegfried Sassoon, who reappeared in Pat Barkers Regeneration trilogy; as did an evocative recreation of the atmosphere around the Billing affair. In the meantime, the trial resurfaced in my research on Noel Cowards early life; reading original copies of the Imperialist and the Vigilante was a chilling experience, yet more so as the political complexion of Billings campaign became clear. Discovering Michael Kettles account in Salomes Last Veil (another coincidence; I had already decided on my title) led me to other, wider conclusions. This book owes much to Dr Kettle, Felix Cherniavsky, and the other historians and biographers on whose work I have drawn.

I am also indebted to Hugo Vickers for his usual clear-eyed and practical assistance. Mark Ashurst, Michael Bracewell, Peter Goddard, Clare Goddard, Robert Holden, Christina Larcombe-Moore and Neil Tennant provided encouragement and intellectual vision. Many others contributed material and ideas, among them: Elaine Burrows, Peter Burton, Jane Bywaters, Roger Cazalet, Terry Charman, Karl Chatfield-Moore, James Chatfield-Moore, Michael Cockerell, Bryan Connon, Betty Eastman, Claire Eastman, Stephen Fry, James Gardiner, Katherine Goonetillake, Alix Holden, Michael Holden, Clyde Jeavons, Adam Low, Stephen Moore, Theresa Moore, Peter Parker, Terence Pepper, Jane Preston, Kenneth Rose, Patricia Thompson, Paul Walter, John Waters, and Simon Watney. Vivienne Westwood supplied sartorial inspiration.

I should also like to thank the following institutions: the British Library Department of Manuscripts and Newspaper Library; Associated Newspapers; the Imperial War Museum; Royal Victoria Park, Netley; the British Film Institute; the Southern Daily Echo ; Johannesburg Art Gallery; Somerset House; the Guildhall Library; the Barbican Library; and the Theatre Museum.

Lastly, I must thank my agent, the redoubtable Gillon Aitken; Robin Baird-Smith, my elegant, patient publisher; and all the staff at Duckworth who made this book possible.

Philip Hoare, Shoreditch, 1997

Introduction

They may be yellow and crumbling, but pages of the January 1918 edition of the Imperialist newspaper still make startling reading. There exists in the Cabinet Noir of a certain German Prince a book compiled by the Secret Service from reports of German agents who have infested this country for the past 20 years, it reports. In the beginning of the book is a precis of general instructions regarding the propagation of evils which all decent men thought had perished in Sodom and Lesbia. The blasphemous compilers even speak of the Groves and High Places mentioned in the Bible There are the names of 47,000 English men and women Privy Councillors, wives of Cabinet Ministers, even Cabinet Ministers themselves, diplomats, poets, bankers, editors, newspaper proprietors, and members of His Majestys Household prevented from putting their full strength into the war by corruption and blackmail and fear of exposure. No English man would be naturally guilty of such offences: it required the filthy Hun to lead him on. Naval dockyards and engine rooms were infiltrated, and the stamina of British sailors was undermined Even to loiter in the streets was not immune agents of the Kaiser were stationed at such places as Marble Arch and Hyde Park Corner Wives of men in supreme position were entangled. In Lesbian ecstasy the most sacred secrets of State were betrayed. The sexual peculiarities of members of the peerage were used as a leverage to open fruitful fields for espionage.

The publisher of the Imperialist was Noel Pemberton Billing, thirty-seven-year-old Independent member of parliament for East Hertfordshire. A man of notable prejudices, he had been indicted for libel on at least two previous occasions, as well as being often censured for unparliamentary language and the odd prosecution for driving at excessive speed. His politics were unerringly jingoistic: he called for internment of all enemy aliens, as well as punitive bombing of German cities; he called the scorn of his Parliamentary opponents the laughter of fools. But Billings latest campaign was a tour-de-force of prejudice, encompassing his manifold obsessions in one almighty conspiracy theory. At its centre was the allegation that the 47,000 were ruled by the still extant cult of Oscar Wilde, a foreign decadence corrupting the cultural and political elite. Billings claims struck deep into the sensibilities of wartime Britain and its leaders, sensitive to criticism of the way the war was being fought. His allegations played on deep-seated ideas of nationalism, xenophobia, homophobia and anti-semitism which remain with us today.

The past is always changing; history never stays the same. It is constantly revising itself, and when it does, we realise how much things have changed, and how little. Even at the end of the twentieth century, the First World War is still only a generation or two away. The poignant songs I learnt as a child Its a Long Way to Tipperary, Pack Up Your Troubles, The Roses of Picardy were sung to my mother by her father, who served in the war; my great-uncle was gassed on the Somme and suffered shellshock; a slow death for him, sometime in the 1920s. No family went untouched by the war, and for this reason, the modern memory of the catastrophe remains vivid. How could something so horrific have happened to a civilised world, so recently? It is part of the reason for the current interest in the period; so too is the fact that its unprecedented horrors set the tone for a century of violence. And yet our conception of the First World War is ironically romanticised by that horror, seen through grainy black-and-white film, the unremitting mud, blood and carnage replayed in slow-motion; patriotic scenes of union jacks on railway stations, women with white feathers, khaki troops singing as they march to war, heroically wounded when and if they return. It is difficult to imagine that any other life went on beyond the central, consuming fact of Armageddon.

Next page

![Wilde Oscar - The secret life of Oscar Wilde: [an intimate biography]](/uploads/posts/book/228457/thumbs/wilde-oscar-the-secret-life-of-oscar-wilde-an.jpg)

Contents

Contents