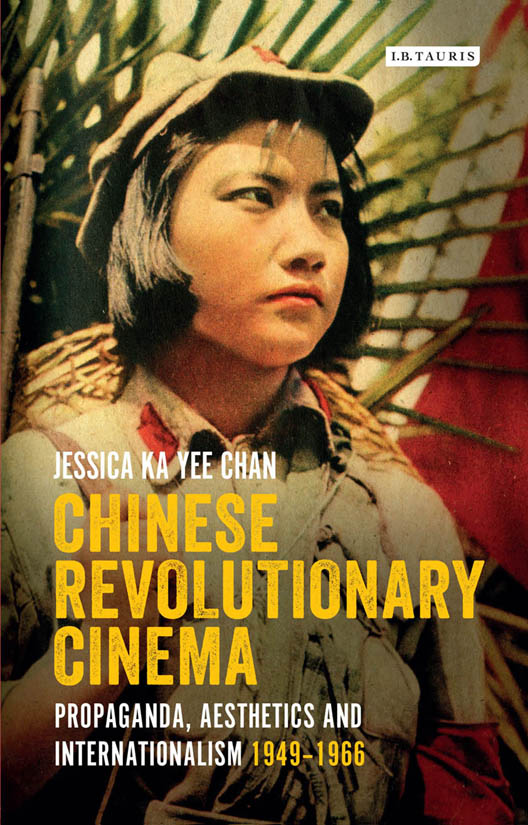

Jessica Ka Yee Chan is Assistant Professor of Chinese Studies at the University of Richmond, USA. She has published in the East Asian Journal of Popular Culture, the Journal of Chinese Cinemas, Modern Chinese Literature and Culture, and The Opera Quarterly.

A long-awaited book that sheds new light on revolutionary Chinese cinema. Eloquently written, it opens our eyes not only to these films politics, but also to their forms and artistry.

Victor Fan, Senior Lecturer in Film Studies,

Kings College London

Chinese Revolutionary Cinema is based on meticulous research and insightful analysis. Avoiding Cold War rhetoric, Chan brilliantly shows how Maoist cinema interacted with Hollywood and Soviet paradigms, as it adapted melodramatic structures, montage theory, and star promotion to the revolutionary cause.

Yomi Braester, Byron W. and Alice L. Lockwood

Professor in the Humanities, University of Washington, USA

For my parents

Published in 2019 by

I.B.Tauris & Co. Ltd

London New York

www.ibtauris.com

Copyright 2019 Jessica Ka Yee Chan

The right of Jessica Ka Yee Chan to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted

by the author in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof,

may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted,

in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or

otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Every attempt has been made to gain permission for the use of the images

in this book. Any omissions will be rectified in future editions.

References to websites were correct at the time of writing.

International Library of the Moving Image 48

ISBN: 978 1 78831 190 8

eISBN: 978 1 78672 434 2

ePDF: 978 1 78673 434 1

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: available

Contents

List of Illustrations

Tables

Principles of classical Hollywood narration that characterise American cinema from 1917 to 1960.

Pudovkins and Eisensteins categories of montage.

Ji Zhifengs Mengtaiqi jiqiao qiantan (A Brief Introduction to Montage Techniques) (1962) is divided into nine sections, which together establish montage as a general term for all editing methods.

Major principles of Stanislavskis system.

Figures

The physical act of turning the pages, accompanied by the off-screen voice of the protagonistnarrator, functions as a cinematic punctuation that divides the film into sequences. This Life of Mine (1950).

The final shot of This Life of Mine (1950).

Xianglin Saos transformation from hostility to awakened love to the establishment of a family is conveyed in eight shots with elliptical editing. The New Years Sacrifice (1956).

The 1956 film adaptation of The New Years Sacrifice, the first colour narrative film (caise gushipian) in the PRC, offered an unprecedented immediacy in visualising Ah Maos melodramatic death.

Appearing five times during the New Year celebrations in the film, the fish used for the ancestral offering functions as a moral symbol and a reminder of Xianglin Saos plight. The New Years Sacrifice (1956).

The film adaptations most controversial sequence: Xianglin Sao in a frenzy, violently hacking away the temple threshold with a cleaver. This sequence, absent in the original literary text, led contemporary audiences to debate the interpretation of Xianglin Saos character. The New Years Sacrifice (1956).

The added scene at the threshold of the temple was seen by some critics as a politically motivated violation of the short storys realism, while director Xia Yan and lead actress Bai Yang said it depicted Xianglin Saos impulsive emotional explosion. The New Years Sacrifice (1956).

A contrast montage sequence that establishes parallel actions in The New Woman (1934).

A split-screen montage sequence that establishes contrast as well as parallel actions. The New Woman (1934).

Shi Dongshan considered the mass slaughter sequence in Eisensteins Strike (1925) an example of contrastive editing.

Ji Zhifeng illustrated the correlation between shot distance and emotional intensity as a curve, which he called the curve of emotional development. The shorter the shot distance, the higher the emotional intensity. The X-axis labels read (from left to right): long shot, medium shot, medium close-up shot, medium shot and long shot. Courtesy of the Chinese University of Hong Kong Library.

Fast cutting is combined with a revolutionary song in a montage sequence in Gate Number Six (1952).

A montage sequence in Nie Er (1959) that distorts temporalspatial order to re-create a historical continuity that represents revolutionary struggle.

The use of internal montage in Stage Sisters (1965).

Relay of gazes in a montage sequence in Pudovkins Storm Over Asia (1928).

Relay of gazes from the lead character to supporting characters to passionate onlookers in a montage sequence in Zhao Yiman (1950).

Relay of gazes and empty shots in a montage sequence in Sea Hawk (1959).

An illustration of an establishing shot and a shot/reverse shot that crosses the axis of action in Ji Zhifengs Mengtaiqi jiqiao qiantan (A Brief Introduction to Montage Techniques) (1962). Courtesy of the Chinese University of Hong Kong Library.

The use of shot/reverse shot to orchestrate kisses and physical embrace in a reunion witnessed by Stalin in The Fall of Berlin (1949).

The relay of gazes in Sea Hawk (1959) points to an off-screen space with a defined diegetic object, presenting the hero and the national flag as the heroines (and the ideal audiences) twinned objects of desire.

Neither relayed through other major or supporting characters nor punctuated by empty shots, Qionghuas gaze becomes properly socialist as she leaps to political consciousness as a Party member in The Red Detachment of Women (1961).

The Chinese film journal Film Art (Dianying yishu) (issue 1, 1961) highlighted this shot as a touching (dongrende) moment of solidarity in the SinoSoviet co-production Wind from the East (1959).

Multinational representatives from the Comintern joining hands in Moscow. Wind from the East (1959).

Wang Demin demonstrates that he can read and translate Soviet revolutionary slogans, outsmarting his teacher and brother in arms Matveyev, who struggles with Chinese. Wind from the East (1959).

An illustrated map of Premier Zhou Enlais visits to Albania, Burma, Ceylon, Pakistan and ten countries in Africa, constructing a glittering arc of friendship. Courtesy of the Chinese University of Hong Kong Library.

Plates

The cinematic technique of dotting the dragons eyes in Song of Youth (1959).

Low-contrast, soft frontal lighting is used to emphasise femininity and Ruan Lingyus delicacy of complexion in The Goddess (1934).

A glamorous halo effect created by natural backlight in Song of Youth (1959).

The use of backlight enhances glamour, as if light is emanating from the socialist icon.

Next page