Michael Maar - Bluebeard’s Chamber - Guilt and Confession in Thomas Mann

Here you can read online Michael Maar - Bluebeard’s Chamber - Guilt and Confession in Thomas Mann full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2003, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

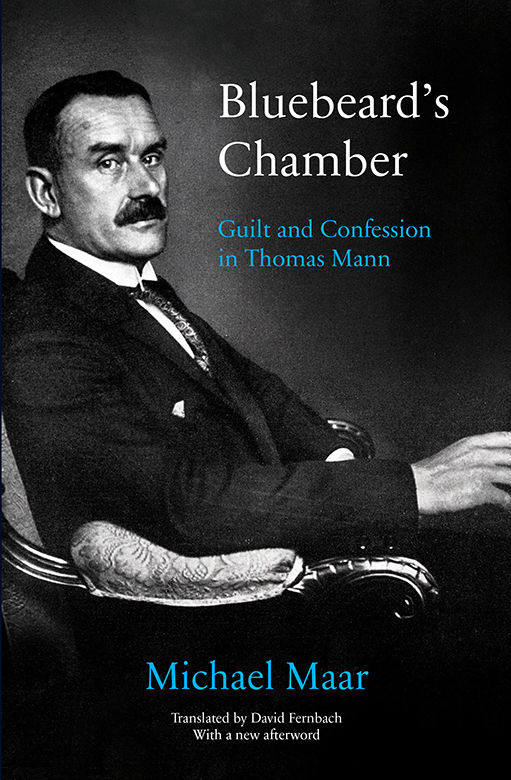

- Book:Bluebeard’s Chamber - Guilt and Confession in Thomas Mann

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:2003

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Bluebeard’s Chamber - Guilt and Confession in Thomas Mann: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Bluebeard’s Chamber - Guilt and Confession in Thomas Mann" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Michael Maar: author's other books

Who wrote Bluebeard’s Chamber - Guilt and Confession in Thomas Mann? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Bluebeard’s Chamber - Guilt and Confession in Thomas Mann — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Bluebeard’s Chamber - Guilt and Confession in Thomas Mann" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Guilt and Confession in Thomas Mann

MICHAEL MAAR

Translated by David Fernbach

This updated edition first published by Verso 2019

First published in English by Verso 2003

First published as Das Blaubartzimmer: Thomas Mann und die Schuld

Suhrkamp Verlag 2000

Translation David Fernbach 2003, 2019

Afterword translation Ross Benjamin 2019

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author and translators have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78663-575-4

ISBN-13: 978-1-78663-577-8 (US EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78663-576-1 (UK EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Typeset in Perpetua by the Running Head Ltd, Cambridge

Printed in the UK by Random House

CONTENTS

T HERE WAS JUST one occasion when Thomas Manns children found him in a state of despair. The maelstrom that swept Germany in 1933 overtook Mann while he was on an extended lecture tour abroad. When he began to suspect that he would be unable to return home, his first anxieties were for a number of notebooks, bound in oilcloth, that he had left locked in a Munich cabinet. These were his old diaries, which he feared might fall into the wrong hands. After weeks of growing disquiet, he forwarded to his son Golo, who was staying in Munich, the keys for the drawers and cupboards, explaining that he wanted the notebooks sent in a suitcase as freight to Lugano. Golo recalls a further instruction:

I am counting on you to be discreet and not read any of these things! A warning I took so seriously that I locked myself into the room while I was packing the papers. When I came out with the suitcase to carry it to the station, there was faithful Hans offering to take this bothersome chore off my hands. All the better, and why not?

It was soon to emerge, however, that Golos excess caution almost proved his fathers undoing. By locking himself in his fathers study, he drew the attention of the chauffeur Hans Holzner, in fact a Nazi informer to the fact that something secret was involved. Holzner did indeed take the suitcase to the station, but he also reported the matter to the political police.

Thomas Mann was now faced with a torment of waiting. On 24 April he noted his disquiet over the suitcases long delay; anxiety put out its first tentacles. Three days later the non-arrival of the case was already uncanny, and he slowly grasped that something was wrong. The following day his suspicion grew firmer: The chauffeur Hans, gradually revealed as a Judas. On 30 April he woke up at five oclock stricken with terrifying thoughts about the suitcase and the diaries. His outward demeanour began to suffer, as we know from the reports of his children. Golo describes how his father fell prey to growing impatience, finally even to despair. And Erika writes of this unprecedented state of excitement, indeed desperation, in which he found himself.

Finally, on 2 May, the all-clear arrived; the case was now on Swiss soil, probably in Lugano: Significant and deep relief. The sense of having escaped a great, even inexpressible, danger, which perhaps never existed at all.

A weighty word, this inexpressible, for a man who knew how to choose his words. And in her own account of those gloomy weeks, his daughter uses equally striking terms:

As it transpired to his relief, the overwhelming issue was the diaries, which he believed not only to be definitively lost, but to have fallen into the hands of a mortal foe. In their unfathomable stupidity, however, they soon released the suitcase quite intact, and T.M., now ready for flight and unwilling to risk a repetition of anything similar, burned a large number of papers at the first opportunity. []

Were they compromising, these neat exercise books? They may well have been. No lifespan is free of a Bluebeards chamber.

Later on Erika tones this down somewhat, explaining that nothing offensive need have occurred. But the Bluebeard metaphor continues to resonate. The little anecdote with which she continues is again far from reassuring:

When [Hugo von] Hoffmannsthal first got to know T.M., still in his youth, he is said to have declared that the entire personal impression he received was of someone uncommonly well-groomed, with an upper-class solidity and discreet elegance. His home, too, gave the same appearance: very fine and spacious, with valuable carpets, dark oil paintings, club armchairs, bright sleeping quarters, etc. The only thing, though, the poet continued, looking down at his fingernails in a little side room there was suddenly lying a dead cat

It is conceivable, then, she concludes this recollection, that it was some dead cat or other that was being burned.

What Erika did not know, and what would have frightened her even given her suspicions, was the entry her father made in his diary on 30 April, at the high point of his despair: My fears now bear first of all and almost exclusively on this assault on the secrets of my life. They are heavy and deep. Something frightful, even deadly, may happen.

This is a passage worth dwelling on rather longer than scholars have done up till now. The meaning seems clear, even if it may be construed in different ways. Does they refer to the fears or to the secrets? Thomas Manns diaries are written in a style that presses ahead with its flow of thoughts, leaving fragments of sentences incomplete, so that they are most likely the secrets; though the adjectives could apply to both, deep secret is a well-established turn of phrase. Such heavy and deep secrets would also make sense of the fatal consequences, as only if they were heavy and deep could their disclosure have the most terrible effect.

But was it Mann himself whom these secrets indicated? In theory, his fears might have been for someone else, exposed in Germany to the vengeance of the Nazis and possibly in imminent danger by being named in this connection. This however is a farfetched speculation and not the meaning immediately suggested, as is also confirmed from another source. Golo, in his autobiography, quotes from the diary that he himself kept at this time. Thomas Mann had spoken about his fears in the family circle: They will publish excerpts in the Vlkischer Beobachter. They will ruin everything, they will ruin me. My life will never be right again. All this dished out to a scornful press free of any legal restraint it is easy to imagine how such a campaign might destroy even a stronger person, so why not Thomas Mann, who took decades to digest lesser insults?

But so utterly shattered as to entertain thoughts of death? Even the new rulers of Germany would need something tangible, and they were still far from deciding how to deal with the Nobel prizewinner, a German national living legally abroad who at this point had still refrained from public declarations against the Nazi regime, and whose works were still available in the bookshops. There certainly was a group that sought in any event to get rid of him, but before his letter to the rector of Bonn University, there was still the vague possibility that he might return, and this tied the regimes hands. So the secrets really must have been heavy and deep, to give the enemy a deadly weapon that could strike its victim even on neutral territory.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Bluebeard’s Chamber - Guilt and Confession in Thomas Mann»

Look at similar books to Bluebeard’s Chamber - Guilt and Confession in Thomas Mann. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Bluebeard’s Chamber - Guilt and Confession in Thomas Mann and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.