Kagan - The Fall of the Athenian Empire

Here you can read online Kagan - The Fall of the Athenian Empire full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2013, publisher: Cornell University Press, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

The Fall of the Athenian Empire: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Fall of the Athenian Empire" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

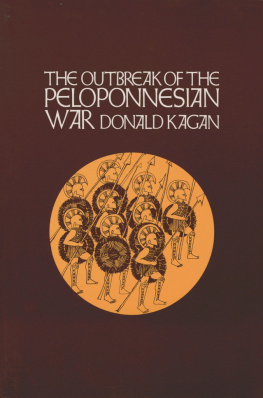

Kagan: author's other books

Who wrote The Fall of the Athenian Empire? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

The Fall of the Athenian Empire — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Fall of the Athenian Empire" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The Fall of the

Athenian Empire

DONALD KAGAN

Cornell University Press

ITHACA AND LONDON

For Bob and Fred, the best of sons

Preface

This is the last volume of a history of the Peloponnesian War. It treats the period from the destruction of Athens Sicilian expedition in September of 413 to the Athenian surrender in the spring of 404. Thucydides history of the war is incomplete, and the eighth book, which breaks off abruptly in the year 411/10, is thought to be unfinished, and unpolished as well. In spite of the incompleteness of his account, his description and interpretation of the war inspire and shape this volume, as they have my earlier ones. The first volume attempted to evaluate his view of the causes and origins of the war as he expresses it in 1.23 and 1.88. The second one examined his assessment of Pericles strategy in 2.65. The third one addressed his judgment of the Sicilian expedition set forth in the same passage and his estimate of the career of Nicias presented in 7.86.

Thucydides judgment of the last part of the war appears in 2.65.1213, at the end of his long eulogy of Pericles and his policies:

Yet after their defeat in Sicily, where they lost most of their fleet as well as the rest of their force, and faction had already broken out in Athens, they nevertheless held out for ten more years, not only against their previous enemies and the Sicilians who joined them and most of their allies, who rebelled against them, but also later against Cyrus, son of the Great King, who provided money to the Peloponnesians for a navy. Nor did they give in until they destroyed themselves by falling upon one another because of private quarrels.

This passage implies that even after the disaster in Sicily and the new problems it caused, Athens might still have avoided defeat but for internal dissension. A study of the last decade of the war enables us to evaluate Thucydides interpretation of the reasons for Athens defeat and the destruction of the Athenian Empire. It also makes possible an examination and evaluation of the performance of the Athenian democracy as it faced its most serious challenge.

For the course of the war, after Thucydides account breaks off in 411, we rely directly on several ancient writers, only one of whom was contemporary with the events he described, and none of whom approached the genius of Thucydides. Modern historians of the classical period like to follow, when they can, the narrative historical account that they judge to be the most reliable, and they tend to prefer it to other evidence from sources that they consider less trustworthy. Whatever its merits in general, this practice is unwise for the period between 411 and 404 B.C. Of the extant writers of narrative accounts, Xenophon alone was a contemporary, and his Hellenica presents a continuous description of the events of that time. It is natural, therefore, that modern historians should at first have preferred his Hellenica to the abbreviated, derivative, and much later account of Diodorus and to the brief, selective biographies of Plutarch, which were aimed at providing moral lessons and were written even later.

The discovery of the papyrus containing the Hellenica Oxyrhynchia in 1906, however, changed the situation drastically. Although its author is unknown, the work seems to have been a detailed and careful continuation of Thucydides history. As G. L. Barber notes, the papyrus indicates a strict chronological arrangement by summers and winters, competent criticism and analysis of motives, a first-hand knowledge of the topography of Asia Minor, and certain details found in no other work on the period. That does not mean, however, that we should merely reverse the traditional practice and always follow the Diodoran account when it disagrees with Xenophon. Neither source is full enough or reliable enough to deserve preference prima facie.

Nor can we ignore the contributions of Plutarch in trying to construct a reliable account of what happened. Although he lived half a millennium after the war, Plutarch had a splendid library of works, many of them lost to us, capable of illuminating the course of events. He knew comedies by lost poets of the fifth century such as Telecleides, Phrynichus, Eupolis, Archippus, and Plato Comicus, histories by Thucydides contemporaries Philistus and Hellanicus as well as his continuators Ephorus and Theopompus. He had access to contemporary inscribed documents; he could see with his own eyes many paintings and sculptures of the fifth century. We may derive a reasonable idea of his value from one of his own accounts of his method: Those deeds which Thucydides and Philistus have set forthI have run over briefly, and with no unnecessary detail, in order to escape the reputation of utter carelessness and sloth; but those details which have escaped most writers, and which others have mentioned casually, or which are found on ancient votive offerings or in public decrees, these I have tried to collect, not massing together useless material of research, but handing on such as furthers the appreciation of character and temperament. In pursuing his own purposes he has provided us with precious and authentic information available nowhere else; we ignore him at our peril.

These three authorsXenophon, Diodorus, and Plutarchare all important, but none is dominant. Where their accounts disagree, we have no way, a priori, to know whom to follow. In each case, we must keep an open mind and resolve discrepancies by using all the evidence and the best judgment we can muster. Wherever possible, I have explained the reasons for my preference in the notes, but sometimes my judgments rest on nothing more solid than my best understanding of each situation. Inevitably, that will seem arbitrary in some cases, but the nature of the evidence about the quality of the sources permits no greater consistency. Introducing and following any general rule would surely lead to more errors than the application of independent judgment in each case.

One further question of method deserves attention. More than one able and sympathetic critic of my earlier volumes has been troubled by my practice of comparing what took place with what might have happened had individuals or peoples taken different actions and by my penchant for the subjunctive mood, or what is sometimes called counterfactual history. To my mind, no one who aims to write a history rather than a chronicle can avoid discussing what might have happened; the only question is how explicitly one reveals what one is doing. A major difference between historians and chroniclers is that historians interpret what they recount, that is, they make judgments about it. There is no way that the historian can judge that one action or policy was wise or foolish without saying, or implying, that it was better or worse than some other that might have been employed, which is, after all, counterfactual history. No doubt my method has been influenced by the great historian whom I have been studying for three decades, who engages in this practice very frequently and more openly than most. Let two examples suffice. In his explanation of the great length of the Greeks siege of Troy, Thucydides says: But if they had taken with them an abundant supply of food, andhad carried on the war continuously, the would easily have prevailed in battle and taken the city. I believe that there are important advantages in such explicitness: it puts the reader on notice that the statement in question is a judgment, an interpretation, rather than a fact, and it helps avoid the excessive power of the fait accompli, making clear that what really occurred was not the inevitable outcome of superhuman forces but the result of decisions by human beings and suggesting that both the decisions and their outcomes could well have been different. In this volume of my history of the war, I shall continue to be explicit in making such judgments.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Fall of the Athenian Empire»

Look at similar books to The Fall of the Athenian Empire. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Fall of the Athenian Empire and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.