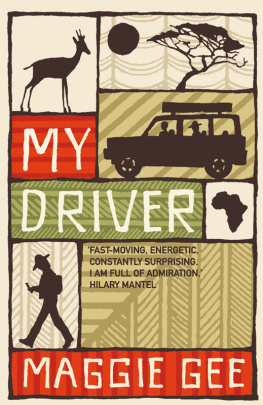

Maggie Gee

MY DRIVER

TELEGRAM

PART 1

In-Flight Entertainment

1

The sun is rising on Uganda. Light streams across Africa as the rim of the earth turns slowly towards it. It gilds the mountains, it floods the plains.

In London, people are still asleep, though Vanessa Henman hasnt slept a wink. (This evening, she will be flying to Kampala, and of course, she will have to get to the airport. Shes tried to contact her ex-husband, who is obviously the right person to drive her. But he has been mysteriously hard to get hold of, and recently Soraya, his new girlfriend, is less friendly. So naturally, her son will drive her. But still she is nervous. Africa!)

She looks at her watch: its 5 AM. She tries to visualise how it will be. She imagines the sun, rising on Uganda. Noise, colour. A river of black faces. River not sea, theres no sea in Uganda. Which sits right on the equator, in the middle of Africa. What does she remember? Loud, honking taxis on Kampalas main street, white Toyota vans spilling fumes and people. But the details ... no, its still out of focus.

In Bwindi, western Uganda, near Congo and Rwanda, countless columns of soldier ants pour through the jungle, moving fast and low, layers upon layers, running over each others backs and onwards, glossy, unstoppable, rivers of treacle, some smaller, reddish, others larger and blacker. Anything in their path, they eat (except the gorillas, who sometimes eat the ants, scooping them into their mouths in handfuls, until the stings are beyond bearing). Its cool and damp here, up in the hills.

The apes are just waking in their nests, great trampled baskets of wet green tree-ferns. They live in cloud white nets and shrouds. Webs of pale rain blow across like curtains, veiling Bwindi Impenetrable Forest. A large grey furry hand extends, slowly, and plucks some breakfast. Its owner has a name, Ruhondeza, given him by humans, but he only knows he is the chief, the silverback, that he has been chief for years and years, though the family is getting smaller. He is staring at a tiny baby gorilla, skinny, little spider-legs and a great quiff of hair, sleeping curled up against the dugs of his mother. Ruhondeza frowns; something very important. He is the chief, but is he the father?

Not far away, there are human soldiers, bearing a confusing variety of initials: the UPDF, the ADF, the PRA, the FDLR, the FNL, Laurent Nkundas rebel army, and remnants of the LRA, the Lords Resistance Army, driven down south from Sudan. Too many names, too hard to remember. Many of the soldiers do not know what they are called. Most of them long to give it up and come home. But have they done things for which they can never be forgiven? Who is to decide what can be pardoned? The peace talks at Juba have been quiet for a while, and in the long nights it is hard to be hopeful. This soldier wears only rags of uniform, dead mens trousers, a dented cap, though he is a sergeant in the LRA. The gentle rain soaks through his clothes. Is he a boy or a man? A short-range radio crackles into life and his cortisol levels jag and peak with the daylight. A new day, another day to kill or be killed, though the newspapers talk about pacts, amnesties.

In Kampala, the capital, an eleven-hour drive north-east, cloud streams up, grey and thick, but moving swiftly: soon it will be hot. A marabou stork a karoli struts magisterially on the pavement, tall as the humans, who dont appear to like him, his long hairy pink gizzard swinging in the light like a warm, greedy chain of office. He cocks his head, and looks wise and cynical. A tourist behind glass in a jeep is thrilled, and takes a photograph. Smartly-dressed people are walking to work, in immaculate shirts and liquorice-shiny shoes, though the pavements are broken, red and dusty. The traffic is thickening: the taxis start hooting. They hold fourteen people, assorted bags of millet and potatoes, and crucifixes meant to keep the drivers safe from other drivers. Men ride boda-boda bikes crowned with thick hooked stems of green bananas, or with wives, in brilliant pink or turquoise, perched side-saddle behind them. Everyone drives more or less in the middle of the road, which seems to offer the best chance of getting where youre going. But mostly, Kampala seems peaceful, and organised.

Mary Tendos in Kampala, getting ready for a trip. She checks her glossy helmet of hair in the mirror and smiles at herself: red plump lips. She is not too slim, which is excellent, for she wants to look good to go to the village. Its her last week at work before the journey, and she has to make sure all the right checks have been done. The first hour of the day, between seven and eight, is always her favourite, with the Executive Housekeepers Office to herself, her computer screen glowing blue and orderly. Time to get a grasp on what there is to be done on this particular morning at the Sheraton.

Its the whitest, straightest hotel in Kampala, and the most modern, until a few years ago. Now it still stands tall on its flowering green hill in Nakasero, where the rich people live, but it seems to be straining up on tip toe, anxious. The truth is the Sheraton suddenly has rivals the boutique Emin Pasha, the enormous new Serena, whose rooms are rumoured to be best of all. The Sheraton staff, too, are slightly nervous; everyone must be on top of their game. Someone important is coming to Kampala.

But outside the banks, down on the teeming main road, the navy-clad, rifle-toting guards can risk feeling sleepy as the sun gets hotter. Their rifles droop towards the ground. No-one is going to challenge them. Its a safe city, with a disciplined army. President Musevenis on top of things. (Hes been on top of things for rather too long. Rather too much on top of things. He is rumoured to be going for a fourth term of office, and the First Family is getting richer. But give him his due, he has disciplined the army, at least when they are close to home.)

A lot of building work is in progress. Round the Parliament building, and near the Serena, pavements are being mended, with pick-axes and new white paving-stones, ready for the next torrential rains, which will wash the red mud underneath away, and spread new red diasporas of earth across the whiteness.

Hotels are going up: more slowly, theyre falling down again. A skyscraper that rose up five years ago, right at the centre of the city, on Kampala Road, made of shiny pink stone, pointing boldly at the future, is peeling in the tropical heat and rain; long shreds of pink skin wave from head to foot, blowing in the wind, flapping hard against its body, and under the torn scraps of rosy veneer are grey panels of what appears to be cardboard. It will have to be mended, like everything else.

Mary Tendo frowns and smiles as she peers at her screen. She refuses to wear her glasses at work. Glasses are ageing; she is strong, and young. Hotel occupancys 67 per cent, at the moment, not bad in view of all the renovations being done. For CHOGM is approaching, pronounced chogamu, though British people call it choggum: two months away, less than two months, the Commonwealth Heads of Government will be meeting in Kampala. And the Queen, the Queen will be coming to Uganda.

Though not to stay at the Sheraton. The Queen will be staying at the Serena, or so it is rumoured. Mary tuts, softly. That ugly, dirt-red, overpriced hotel. With its terrible history, which we will not speak about (though the Sheraton has its own history, which Mary Tendo is used to denying. People whisper that, under Idi Amin, in the bad old days of Big Daddy, they used to hear screams in the middle of the night. But its all so long ago it must be forgotten, or else Uganda cannot move into the future. Ugandans have become good at forgetting; and many of them are forgiving, also.) Mary is sure that the Queen did not choose to go to the Serena instead of the Sheraton.