ALSO BY SHALOM AUSLANDER

Foreskins Lament

Beware of God: Stories

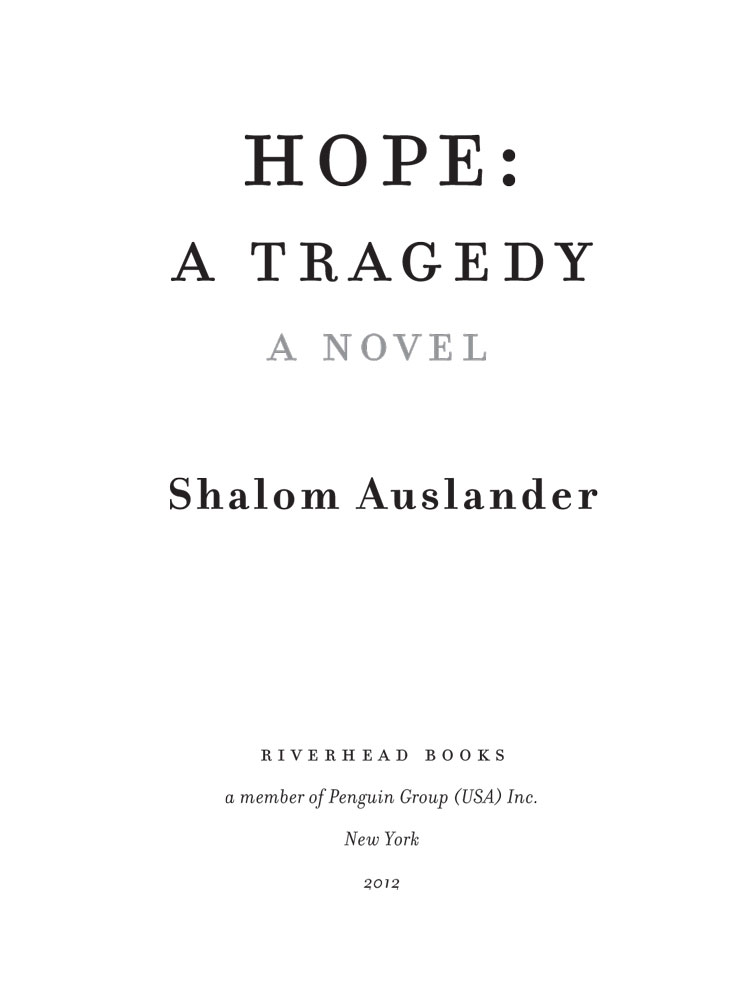

HOPE:

A TRAGEDY

A NOVEL

Shalom Auslander

RIVERHEAD BOOKS

a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

New York

2012

RIVERHEAD BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi110 017, India Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Copyright 2012 by Shalom Auslander

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the authors rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

Published simultaneously in Canada

ISBN 978-1-101-56128-7

BOOK DESIGN BY NICOLE LAROCHE

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the authors imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers and Internet addresses at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Contents

We were liberated from death,

from the fear of death;

but the fear of life started.

H. Rosensaft, Yesterday: My Story

Hide in the sky,

hide in the sky,

who wants to come with me

and hide in the sky?

Serj Tankian

ITS FUNNY: it isnt the fire that kills you, its the smoke.

There you are, pounding on the windows, climbing higher and higher through your burning home, trying to get away, to get out, hoping that if you can just avoid the flames, perhaps youll survive the fire, but all the time youre suffocating slowly, your lungs filling with smoke. There you are, waiting for the horrors to come from some there, from some other, from without, and all the while youre dying, bit by airless bit, from within.

You buy a handgunfor protection, you sayand drop dead that night from a heart attack.

You put locks on your doors. You put bars on your windows. You put gates around your house. The doctor phones: Its cancer, he says.

Swimming frantically up to the surface to escape from a menacing shark, you get the bends and drown.

You resolve, one sunny New Years Day, to get back into shape. This is the year, you insist. A new beginning. A new start. A stronger you, a tougher you. At the health club the following morning, just as youre beginning your third set of bench presses, your muscles cramp and the barbell collapses onto your neck, crushing your windpipe. You cant cry out. Your face turns blue. Your arms go limp. There, on a poster on the wall beside you, are the last words you see before your eyes close and darkness envelopes you for eternity:

Feel the Burn.

Its funny.

SOLOMON KUGEL WAS LYING IN BED, thinking about suffocating to death in a house fire, because he was an optimist. This was according to his trusted guide and adviser, Professor Jove. So desperate was Kugel for things to turn out for the best, proclaimed Professor Jove, that he couldnt stop worrying about the worst. Hope, said Professor Jove, was Solomon Kugels greatest failing.

Kugel was trying to change. It wouldnt be easy. He hoped that he could.

Kugel stared silently at the ceiling above his bed and listened.

He heard something.

He was certain of it.

Up there.

In the attic.

What is that? he wondered.

A scratching?

A rapping?

A tap-tap-tapping.

The other reason Solomon Kugel was lying in bed, thinking about suffocating to death in a house fire, was that someone was burning down farmhouses, just like the one he and his wife had recently purchased. The arson began soon after the Kugels moved in; three farmhouses had been torched in the six weeks since. The Stockton chief of police vowed he would catch whoever was responsible. Kugel was hopeful that he would, but hadnt slept since the first farmhouse lit up and burned down.

There it was again.

That sound.

Maybe it was mice.

It was probably mice.

There are a hundred farms around here, jackass. Why would he target you? Its farm country.

Youre frightening yourself.

Youre torturing yourself.

Its narcissistic.

Its delusions of grandeur.

Its optimism.

Its mice.

Didnt sound like mice, though.

Kugel thought frequently about death and even more frequently about dying. Was this, too, he wondered, because he was an optimist? Precisely, Professor Jove had declared. Kugel loved life, observed Professor Jove, and so he expected far too much of it; hell-bent on life, he was terrified that someone would cause, by violence or accident, his untimely death. Kugel, in his own defense, pointed out that he didnt think anyone was actually trying to kill him, he simply thought it well within the realm of possibility that somebody, unbeknownst to him and for reasons yet to be revealed, might be; there is a line, he argued, thin as it may be, between paranoia and pragmatism.

Kugels mother, for her part, worried less about death than she did about life. Her own life, sadly, had gone too well, too smoothly; above average in comfort and security, below average in suffering and pain; better than anyone had a right to expect and callously lasting far longer than anyone could rightly demand. Alive, and happy, she cried.

Kugel thought specifically about the experience of dying. He thought about the pain, about the fear. Most of all, he thought about what he would say at the final moment; his ultima verba; his last words. They should be wise, he decided, which is not to say morose or obtuse; simply that they should mean something, amount to something. They should reveal, illuminate. He didnt want to be caught by surprise, speechless, gasping, not knowing at the very last moment what to say.

No, wait, I oof.

I havent really given it much splat.

If I could just ka-blammo.

We are all mankind a story, collectively and individually, and Kugel didnt want his individual story to end in an ellipsis. A period, sure, if youre lucky. An exclamation mark, okay. A question mark, probably; that seemed the punctuation all stories, collectively and individually, should end with after all.