CONTENTS

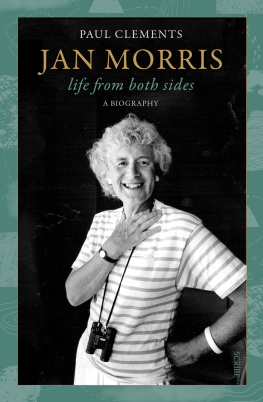

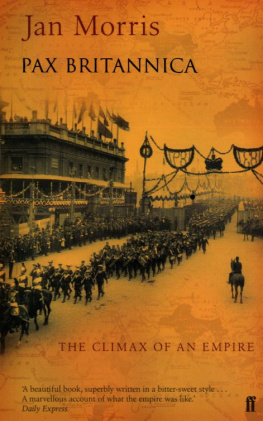

Jan Morris is one of the great British writers of the post-war era. Soldier, journalist, writer about places (rather than travel writer), elegist of the British Empire, novelist, she has fashioned a distinctive prose style that is elegant, fastidious, supple, and sometimes gloriously gaudy. Now in her ninety-first year, she has written more than forty full-length books, has contributed in one way or another to many others, and has written countless essays, articles and reviews. She writes in an unashamedly subjective way, and it is hardly an exaggeration to say that she has imposed her personality on the entire world. Born in 1926, James Morris, as Jan was until 1972, was fortunate to reach maturity in a world of general stability and ease of movement. No one before or since has travelled and written in quite the same way. Jan Morris is sui generis.

I first met her in the offices of the publisher Random House in New York in the early 1980s. I was a junior editor there, and was invited to meet someone I considered to be one of the most intriguing writers I had read. This was nothing more than a handshake and an acknowledgement of our shared Britishness in New York. But I was immediately struck by Jans warmth and affability, qualities that are key to her genius for talking to people and drawing stories from them. (For while Jan is less of an extrovert in person than in her writings, and indeed in some ways is quite reserved, she nonetheless possesses a remarkable ability, surely learned in the world of journalism, to nose out a story.)

Ten years later I had the privilege of becoming Jans literary agent at A. P. Watt, taking over from someone who had left the firm. I remained in this role until I retired from full-time agenting in 2013. We stayed in touch, however, and our meetings led to the idea of this book. Ariel is not a conventional biography. It is structured more thematically than chronologically, and my observations about Jans life proceed from the work, rather than the other way around. I have quoted extensively from Jans books, as a way both to tell the story of her life and to demonstrate the range and depth of her writing. (All the words in quotation marks, unless otherwise indicated, are Jans.) Taken together, Jans books run to somewhere between three and four million words. I hope that the quoting of a few thousand here will whet readers appetite for more.

This book is not authorised, though I have interviewed Jan on several occasions, and she has made available correspondence, press cuttings and other materials in her possession. Jan has never been a prolific private correspondent, however, and has not kept diaries. The essence of her thoughts and feelings seems to me to reside in the writings themselves. Nor is Ariel in any way a scholarly work, something which in any case I am not qualified to write. It is an appreciation of the life and work of one of the most remarkable people I have known.

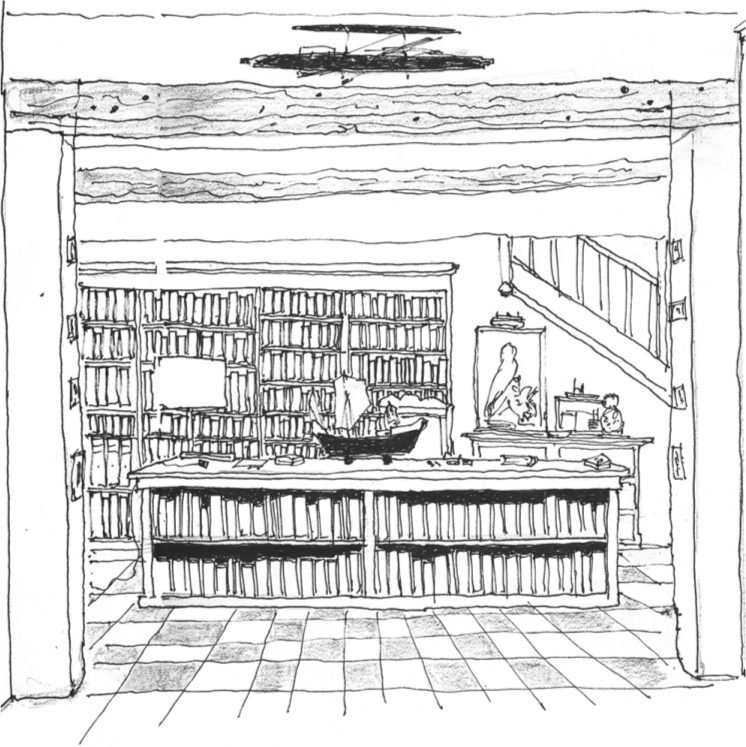

Hardly less remarkable than Jans abilities as a writer is her ability as an artist, and the pages of this book are adorned by a number of her line drawings.

I should say that given my personal relationship with the subject, and given also her mid-life gender reassignment, I have referred to Jan throughout, except when it makes more sense to refer to James, as when I am describing the actual experiences she had while she was a man.

She is one of those few cities that are more than cities, that reflect the meaning of a civilization, and thus belong not to a nation, but to the world.

James Morris was born in 1926 in Clevedon, Somerset, the son of a Welsh father and an English mother. He sprang from a long line of odd forbears and unusual unions, Welsh, Norman and Quaker. His mother was a gifted pianist who had studied at the Leipzig Conservatory and in later life gave recitals in Wales and the West Country. It was while James was sitting under her piano, at the age of three or four, listening to her playing a piece by Sibelius, that he decided he was really a girl.

It is interesting to note how little Jan has written about a childhood that must have been overshadowed by this sense of physical oddness. In her book Pleasures of a Tangled Life she refers to being puzzled by this awareness but not unhappy. And in her memoir Conundrum she only begins to describe her life and feelings in details once she has reached her teens.

Jamess two elder brothers both pursued successful careers in music, and while Jan claims to be wholly unmusical, her time as a chorister must have been formative. (Jan is of course in a sense very musical, in the cadences of her sentences; she reads her drafts aloud so as to test their rhythms.) Her father is almost entirely absent from Jans writings, and indeed from her memory. He died when she was twelve, having been badly gassed in the First World War, leaving his wife responsible for the familys upbringing. His principal legacy would appear to have been his Welshness, which later came to be so important an element in Jans life.

James attended a local primary school, and he seems to have had a rather dreamy, solitary childhood, his brothers packed off early to boarding schools. Conundrum describes Jamess wanderings in the hills above the Bristol Channel, and particularly his spying of ships through a telescope. Jan has ever since adored ships of all kinds.

Jamess mother was apparently a somewhat chaotic reader. In Pleasures of a Tangled Life Jan describes her prefer[ring] to read seven or eight books simultaneously, in two or three languages, left propped above washbasins, recumbent on sofas, or unexpectedly on the piano music stand The two books Jan can remember reading as a child are Alices Adventures in Wonderland and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. It is easy to see these two characters as exemplars of the free spirit she became. Alice is a shape-shifter, very proper in her manners but at the same time almost recklessly adventurous. Huck is a nonconformist whose rebellious impulses are moderated by a sense of what is right and an awareness of the feelings of others. These are all qualities Jan herself came to possess.

Oxford made me, Jan writes in Conundrum. At the age of nine James was sent to the Cathedral Choir School at Christ Church in Oxford, and so began a long association with and love of the city. Founded by Cardinal Wolsey and Henry VIII, this was and remains a prep school with a distinctly Christian ethos. It is housed in beautiful buildings close to Christ Church, and its choristers sing in the cathedral chapel. Buildings have inspired Jan throughout her life, and this immersion in surroundings of such beauty, so steeped in English tradition, had a profound and lasting effect on her life and work. As a chorister boarder Jamess daily routine involved prayer and singing, combined with the sort of lessons any school would have provided. It is tempting to say that being a chorister, dressed in a fluttering white gown, was the next best thing to being a girl. A virginal idea was fostered in me by my years at Christ Church, she writes in