A LITTLE GIRL DREAMS OF TAKING THE VEIL

MAX ERNST

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC.

MINEOLA, NEW YORK

Copyright

English translation copyright 1982 by Dorothea Tanning

All rights reserved.

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 2017, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published as Rve dune petite fille qui voulut entrer au Carmel by Editions du Carrefour, Paris, in 1930. Dorothea Tanning translated the work into English.

International Standard Book Number

ISBN-13: 978-0-486-81452-0

ISBN-10: 0-486-81452-1

Manufactured in the United States by LSC Communications

81452101 2017

www.doverpublications.com

TRANSLATORS NOTE

In this the second of Max Ernsts collage novels, published in Paris in 1930, the author has added a new dimension of psychic violence to the already fraught pictures in which night and dream are the sovereign forces that not only color but provoke the inexorable procession of events that defines the dilemma of A Little Girl Dreams of Taking the Veil.

Each one of these collages uses cuttings often from the most banal of the pre-photography illustrated penny novels, and from popular tomes about nature, science, exoticism. Each collage, then, could be analyzed as the sum of its varied components were it not for the dazzling fact that with his art Max Ernst completely transformed his humble materials and so imposes on our retinas and on our minds a formidable blueprint for amazement.

A Little Girl Dreams of Taking the Veil may be seen to embody our most frequent tragedies, our wriest enslavements, our most terrible solutions. Specificity dissolves in the timeless and the general. Max Ernsts collages, telling their oblique story, will be treasured as art and idea. And we will ask ourselves not when or where but what has happened, for them to be so indelibly graven on our memory.

Dorothea Tanning

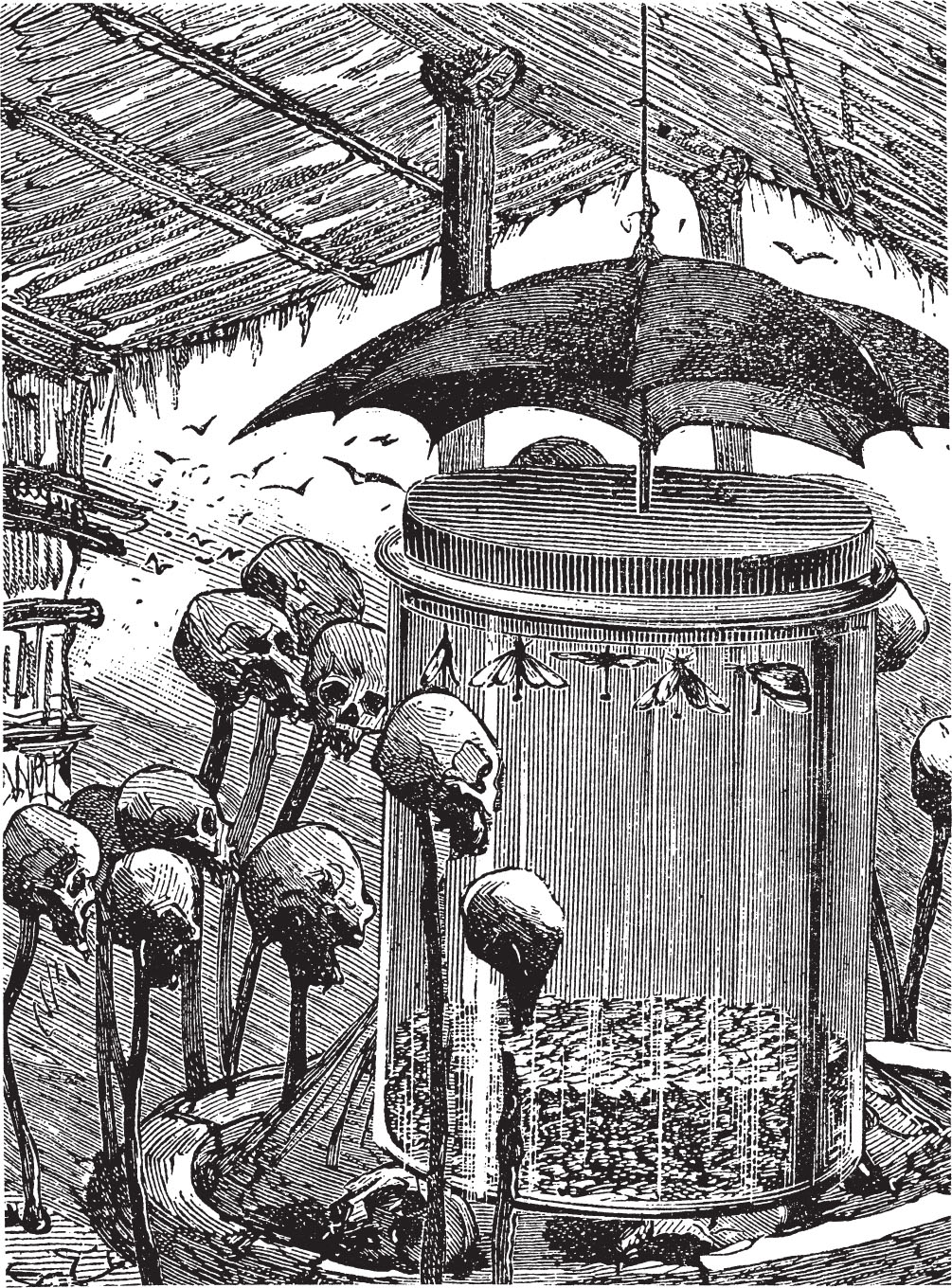

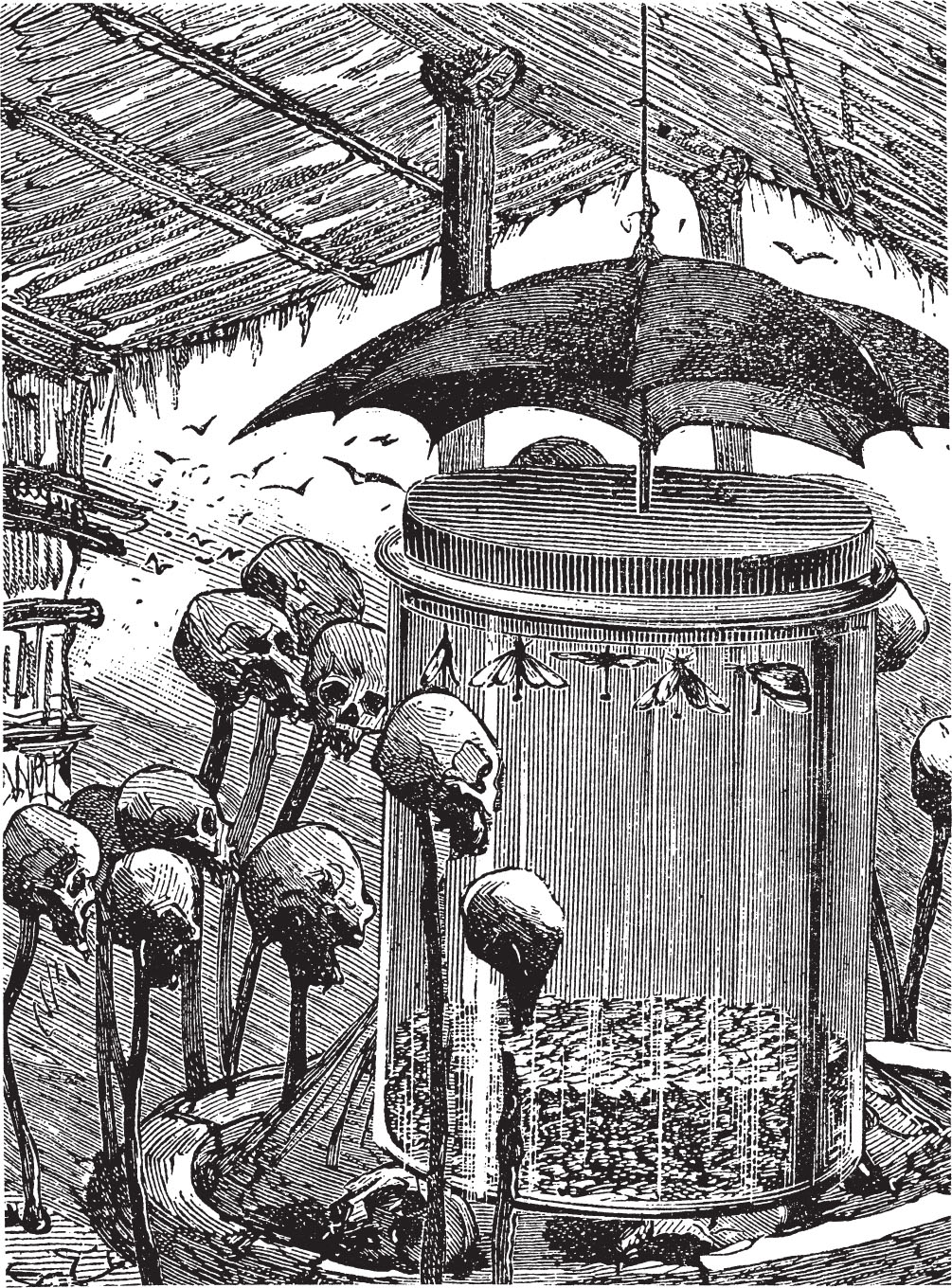

Academy of Science.

The night will come when the Academy of Science itself will not disdain to cast its gaze on the sewers of the world. The night will come when, covered with all their jewels, the secondary skeletons that one calls scientists will ask themselves this question:

What do little girls dream of who want to take the veil?

On that night a violent storm will break against the doors of the Academy of Science and the water will roar in the pipes.

The water will remember the shameful year 1930, the year it would have liked to see all the cathedrals of the universe parade in far-too-short dresses. It will remember above all a certain night because

On Good Friday night of the shameful year 1930 a child hardly sixteen years old dipped her two hands in a sewer, pricked her skin and with her blood traced these lines:

To love the Holy Father and to dip ones hands in a sewer,

such is happiness for us, the children of Mary.

From the Convent of the Visitation at Lyon where she was educated, she sent this phrase by carrier pigeon to her father, Christian-Socialist deputy in Paris, embraced him tenderly in her thoughts, went to bed and had the dream that we will try to relate through pictures in this book.

In the phrase from her letter quoted above it is easy enough to find the irresistible tendency that drew her toward the practice of obstinate devotion and theatrical sacrifice. It is easy to recognize there the precociousness of her beautiful intelligence, of her brilliant imagination, of her ardent heart.

The same powerful sentiment which from her eleventh year moved her to enlist under the banner of Saint Theresa of the Holy Child showed itself very early in her love for the study of Latin: she wrote rather playful phrases in which were revealed sometimes extreme delicacy, sometimes the sparkling verve of a Latin soul:

Diligembimini gloriam inalliterabilem mundi fidelio.

Benedictionem quasimodo feminam multipilem catafaltile astoriae.

At thirteen she called her body her somber prison:

Hidden in the folds of my somber prison multicolored groups represent the various peoples of the world.

It seems to me that these phrases already show an unusual depth of mind and reveal the germs of the extraordinary dream which follows. It may be useful for its comprehension to say here that at age seven and through the savagery of an ignoble individual she lost her virginity. It happened on the very day that first communion was refused her: she was too young, as her milk teeth proved. The individual, not content with having forced her, broke all her teeth with an incredible ferocity and by means of a large stone. Then she came back and said to the Reverend Father Denis Dulac Dessal, while showing him her bloody mouth:

Now I can take communion, I have no more milk teeth.

Though still a little girl too undeveloped to feel all her happiness, she sent nevertheless, again by carrier pigeon, this message to her father:

Oh! I am so happy! How right you were to say that the day of ones first communion is the happiest day of a persons life. Laudate dominum de coelibus catalinenia.

Spontanette.

Spontanette was the name her father had given her because of her lively, alert and playful character, and also because of the large crowns of red vapor that she generally wore around her hips and ankles. Her real name was Marceline-Marie. This double first name is of prime importance in the evolution of the dream that follows. Because it is probably due to the troubles provoked by the coupling of the two names of such a very different signification that we will see her slit herself up the middle of her back from the very beginning of the dream and wear appearances of two distinct but closely related persons. Two sisters, she told herself in dreaming, and called one of them Marceline and the other Marie, or I and my sister. Perhaps one should point out that during the whole dream she only rarely succeeded in identifying herself in a definite way with one of them, and that only at these happy moments did she see herself as she generally appeared, with her real age, her real sex, dressed and combed as usual.

Let us further note that the vocation, which she had wanted with all her heart since the day of her tooth-loss-virginity-loss first communion, came to her at the age of eleven during the benediction for a statue in bronze of the Little Saint of Lisieux. She had remained motionless during the procession of the martyrs relics and during the sermon, that is, for two hours, her arms held out, a knife in her hand to cut open the earth. Then, at the very moment that the seminarists were singing the Hymn of the Ascension of the Children of Mary she floated up from the ground, remained suspended in mid-air for some seconds, and cried out in an inspired and deliriously pure voice which was heard above the choir and the organs:

Enter, dear knife, enter into the incubation chamber!

The celestial bridegroom invites me to the feast!

I sacrifice myself and I give myself!

The earth is soft and white.

Stupified, the seminarists stopped their singing. My child, replied the R. F. Denis Dulac Dessal from the height of the altar, glory to God and to the Holy Church! You have, yes you have, a religious vocation. You must accept what has been offered you, but you are only eleven years old! How grateful you must be to Mary, your well-beloved mother and patron! It is she, never doubt, who has done everythingbefore, during and after.

Before, during and after, intoned the crowd in chorus.

That evening, perhaps by inadvertence, she broke a porcelain bowl, one of those which nightly serve the intimate needs of little girls, and was condemned to pay a fine. She paid the fine, but only after improvising a scene whereby the punishment inflicted by the Mother Superior was rendered ridiculous. She sang until midnight the Wine of Consolations, monotonous chant of penitence sung upon a single repeated note, and got up afterwards to bite the nails of all her sleeping companions. In the morning she stood by the door, at the moment when the bell rang for the little students to leave the dormitory, and holding out to each one a piece of the bowl transformed into a collection plate, and in a voice half sad, half mocking: