Copyright 2018 by Lance Esplund

Cover design by Ann Kirchner

Cover image: The Sun Recircled, 1966 (colour woodcut), Arp, Hans (Jean) (18871966) / The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Israel / The Arthur and Madeleine Chalette Lejwa Collection / Bridgeman Images 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Cover 2018 Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Basic Books

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.basicbooks.com

First Edition: October 2018

Published by Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Basic Books name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Esplund, Lance, author.

Title: The art of looking : how to read modern and contemporary art / Lance Esplund.

Description: First edition. | New York : Basic Books, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018026754 (print) | LCCN 2018028114 (ebook) | ISBN 9780465094677 (ebook) | ISBN 9780465094660 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Art, Modern. | Art appreciation.

Classification: LCC N6490 (ebook) | LCC N6490 .E798 2018 (print) | DDC 709.04dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018026754

ISBNs: 978-0-465-09466-0 (hardcover); 978-0-465-09467-7 (ebook)

E3-20181008-JV-NF

If youve never understood contemporary art, or fear youve understood it all too well, then this book is ready to be your secret friend. In lucid prose that has the loft of poetry, Lance Esplund lifts the burden of art appreciation to reveal that the subject of all great art is how it appreciates you for the way you look at it. His own encounters with exemplary workby Joan Mitchell, James Turrell, and Marina Abramovi among othersare related in terms so complete, courageous, and physically convincing they make you want to see art as he has seen it, a giant step toward seeing it for oneself.

Douglas Crase, author of The Revisionist

The Art of Looking is a wonderful book, filled with remarkable insights about experiencing whatever it is that we mean by the word art. Whether it is Balthus and the Me Too Movement or walking through Richard Serras enormous curving rust colored sculpturesthere is always something new and exciting to be discovered.

Robert Benton

To Evelyn

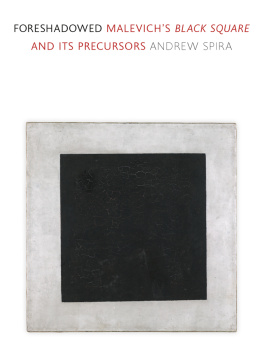

T HE LANDSCAPE OF ART HAS CHANGED DRAMATICALLY during the past one hundred years. Weve seen Kazimir Malevichs Black Square (1915), an abstract painting comprising a single black square within a white ground, and Marcel Duchamps infamous Fountain (1917) (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, the artist Maurizio Cattelan replaced a porcelain toilet in one of the public restrooms with the interactive sculpture Americaa fully functional replica of a toilet, cast in 18-karat gold.

Is it any wonder that the art-viewing public is bewildered, even intimidated? What are they to make of the range of possibilities offered in galleries and museums? Are Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, and Pollock old hat? Is the art of the past century meant primarily to baffle, shock, and provoke us? Are Modern and contemporary artists speaking only to an elitist art-world few or creating inside jokes? Or is the joke, perhaps, on us? And if viewers dont bother to queue up to use Cattelans America, or to see a Jeff Koons, Kara Walker, or Gerhard Richter retrospective, are they missing out? Or is something else afoot? Todays viewers might rightly wonder: Has the public always felt uneasy about and out of step with the art of their time? Or is all the confusion and apprehension a sign of something new and very recentsomething exclusive to the experience of todays contemporary art?

The answers to these questionsjust like the art under discussionare complex and manifold. People have had to grapple with the revolutionary art of their contemporaries throughout history: the jarring, naturalistic sense of space introduced during the Renaissance in the early fourteenth century was just as unsettling and revolutionary as the jarring, antinaturalistic sense of space of Cubism, which upended the Renaissances approach in the early twentieth century, or the jarring objectlessness of Conceptual art in the late twentieth century. Its important to understand that art, despite its relationship to its time, is a language unto itselfa language that exists beyond its particular era. That language continually evolves and reinvents itselfeven often quotes itself. But there are also qualities specific to Modern and contemporary art that are unique.

Definitions of the word artas well as of many of the different terms used to classify arts periods, movements, and ismsare now fluid and open to discussion. Whether any given movement is truly modernas in recentis therefore often up for debate. One could argue, for example, that the twentieth-century movement Surrealism, fueled in part by the workings of the artists unconscious, reached its zenith in the fantastical religious narratives created by the Netherlandish painter Hieronymus Bosch (14501516); or that the Modern movements Expressionism and Cubism were in ascendance already in the angular elongations and fractured spaces of the Spanish painter El Greco (15411614); or that some of the most inventive abstract art was created by medieval nuns and monks, or by the ancient Egyptians. In this book, Ill shed some light on these issues, and perhaps make these movements more approachable, by illuminating the similarities between recent and past art.

Its useful to discuss terminology, because there is such a wide range of work being doneand such a wide range of opinions, philosophies, agendas, and approaches around art. By Modern, Im referring primarily here to artworks made since 1863, when douard Manet exhibited his scandalous painting Le Djeuner sur lherbe (The Luncheon on the Grass) (of the official Paris Salon. Le Djeuner sur lherbe, a painting in which a nude woman, looking at the viewer, picnics with a couple of dandies, was among the first artworks that provocatively and self-consciously questioned and poked fun at the hallowed traditions and conventions of painting. In this case, it was through, among other things, its subject, which transformed the classical nude from goddess and muse into floozy, if not prostitute, and its willfully slapdash paint-handling. But we could start earlier, with the gritty Realist paintings of Gustave Courbet, or later, with Picassos and Georges Braques Cubism. Modern art incorporates not only Manets Impressionism, but also those groundbreaking movements Realism and Cubism, as well as Symbolism, Fauvism, Expressionism, Surrealism, Dadaism, and abstraction, among many others. To be a Modern artist means not so much belonging to a particular era or movement as taking a particular philosophy and stance in relationship to art and art-making.