After a draft of Chapter II of this book had been written, a conversation with the scholar-author W.J. McCormack changed what would become the rest of the book. He gave me a tip that led to Christine Shields in Oakland, California, who was Arthur Shields daughter, Barry Fitzgeralds niece, and Sara Allgoods goddaughter. These are the three great Abbey actors whose work is traced here.

Arthur Shields had been a bookish person, a keeper of mementos and careful manager of his own archive. Fortunately, his daughter was too. On being contacted, she let a visiting scholar come to her home and go through the papers. Christine Shields and her cousins Judith Lunny and Susan Slott then made a gift of this precious archive to the National Library of Ireland, Galway. The photographs alone transformed this book; the letters gave it a heart. As keepers of the flame, Christine Shields, Judith Lunny, and Susan Slott were helpful whenever asked; never when not asked. Their gift of the archive to the library of NUI Galway has already attracted other scholars and will benefit many more in the future.

I began with a desire to picture performances of the early Abbey Theatre. Those historic productions of the Irish dramatic revival were unique and unrepeatable events, never captured, either on film or in writing. But the actors so famous in the 1920s did go on to careers in film. It was in following those careers that one became aware that the great Abbey actors carried the Revival along with them to California, and then carried Hollywood back to Galway in The Quiet Man. That is the simple thesis and trajectory of this book.

A number of friends, family members, and colleagues were kind enough to read the manuscript. My thanks to Kevin Barry, Ros Dixon, John Carney, Kieran Carney, Helen Frazier, Rufus Frazier, Nicholas Grene, John Kenny, Thomas Kilroy, Jim MacKillop, Mike McCormack, Dearbhla Mooney, Riana ODwyer, and many times over, Cliodhna Carney. Also to be thanked are those who invited me to lecture on the subject: Marc Conner at Washington and Lee University; Nicholas Grene at the Synge School of Drama in Wicklow; Dennis Kennedy at the Samuel Beckett Centre, Trinity College Dublin; Lucy McDiarmuid at Montclair State University; Paul Muldoon at Princeton University; and Sen Crosson, Tony Tracy, and Rod Stoneman at the Huston School of Film and Digital Media, NUI Galway.

Richard English and Cormac OMalley gave aid in understanding Ernie OMalleys relationship to John Ford. Joseph Hone worked with Ford when a young man: my thanks for providing an early look at what became Wicked Little Joe. Patrick McGilligan and Scott Eyman two well-known authors with a vast knowledge of American filmmakers, Ford in particular were each helpful, the first with publication advice, the second with images from his own archive.

While this book has been in preparation, three other monographs touching on its subject have been published: Ruth Barton, Acting Irish in Hollywood: From Fitzgerald to Farrell; Barry Monahan, Irelands Theatre on Film: Style, Stars and the National Stage on Screen; and Michael Patrick Gillespie, The Myth of an Irish Cinema: Approaching Irish-Themed Films. There is surprisingly little overlap between the four books. That is partly because the history of Irish cinema is a large field of inquiry, with much left to explore, and partly because there are many ways to come at it. The Internet Movie Database (imdb.com) and its purchasing feature enable one to order cheaply hundreds of historic films that not long ago would have been very difficult to access.

One of the pleasures of writing a biographically ordered story is that it takes one to great libraries. The National Film Information Service at Margaret Herrick Library, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, in the Douglas Fairbanks Center, Beverly Hills, California , is one of the sweetest, best-run places to study; my thanks to Kristine Kruger for the help rendered after my departure. Lauren Buisson at the Arts Library Special Collections, Young Research Library, UCLA , gave assistance in finding a way through the RKO and 20th Century Fox papers. The Lilly Library at Indiana University has the papers of John Ford and Lord Killanin; my thanks to David K. Frasier for dealing with email queries after my visits there. Karen Nangle of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, provided the Sara Allgood photographs. My thanks to Bruce Kellner Trustee, Estate of Carl Van Vechten, for permission to use Vechtens portraits of Allgood.

The special collections librarians at NUI Galway were continuously helpful; my thanks to Fergus Finlay, Marie Boran, and especially Kieran Hoare.

I must officially render my thanks, and am happy to do so sincerely, to the Grant-in-Aid of Publications scheme at NUI Galway (which enabled this book to be richly illustrated); and to the Millennium Fund, NUI Galway, which made possible my travel to archives. I was the beneficiary of an NUI Galway one-year sabbatical, during which much of this book was written; my thanks to colleagues in the English department who covered my teaching responsibilities, particularly Patrick Lonergan and John Kenny. My thanks to Irene OMalley and Dearbhla Mooney, the English Department administrators, for daily making the work environment truly pleasant.

Jonathan Williams, who established Irelands first literary agency, takes remarkable care in the reading of a manuscript, and then the proofs; he has an eagle eye and a perfectionists knowledge of form. My thanks to him for placing the book with Antony Farrells Lilliput Press. There it has been enhanced by the editing of Fiona Dunne, and designed by Marsha Swan. Lilliput has rightly earned a name for publishing not just good books but beautiful ones. Helen Litton gets credit for the index.

There is one final personal nest of motives for writing this book that I wish to uncover. At the time of its beginning, I was the father of two small girls, and did not have time to read a lot of books, much less travel to archives. However, I could, while carrying an infant in my arms, watch movies. What is more, my wife and in-laws were caught up in writing screenplays , directing movies, acting in movies, talking about movies, and arguing about whatever movie they were watching. Steps needed to be taken to catch up at least a little with their expertise. So my heartfelt thanks to Frances Knott and Martin Carney, Jim, John, and Kieran Carney, Lucy Miller and Marcella Plunkett, and, most of all, my wife, Cliodhna Carney.

And, of course, to Clea and Lesy Carney Frazier, no longer infants at all, but very much little ladies who neither would nor could now be carried by me. Without them, I would never have thought to write this book. Now it is Delia Carney Frazier who is the babe in arms, and a reminder of how small a thing, in balance, any book is.

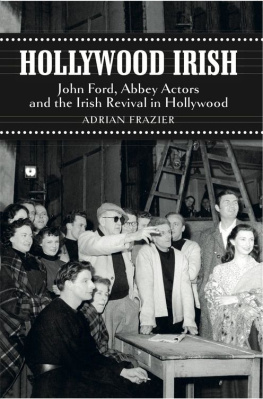

HOLLYWOOD IRISH

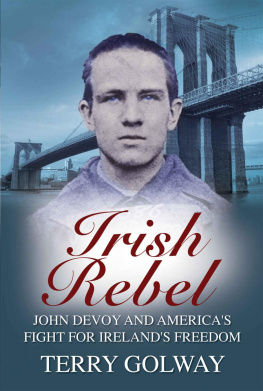

Members of the Abbey Theatre company treated to a lunch with the RKO production team on the set of The Informer, February 1935. John Ford is at the last table, far right. (Shields family papers)

I n 1931, 1932 and 1934, the Abbey Theatre company left Dublin for long tours of its repertoire through the United States. The third tour brought the Irish actors to Hollywood in February 1935. At the time John Ford, an Irish American with a passion for Ireland and its literature, was making a movie for RKO Studios of Liam OFlahertys novel The Informer. A great admirer of the Abbey, Ford staged a welcome banquet for the players on the set of