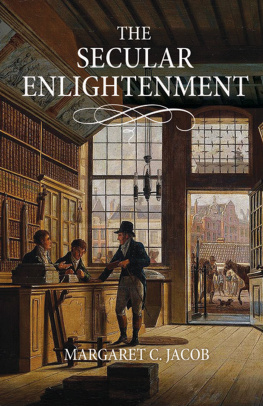

THE SECULAR ENLIGHTENMENT

The Secular Enlightenment

MARGARET C. JACOB

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON & OXFORD

Copyright 2019 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

LCCN 2018946123

ISBN 978-0691-16132-7

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Rob Tempio and Matt Rohal

Production Editorial: Sara Lerner

Jacket Design: Leslie Flis

Jacket Credit: Johannes Jelgerhuis (17701836), The Shop of the Bookdealer, Pieter Meijer Warnars on the Vijgendam in Amsterdam.

Prisma Archivo / Alamy Stock Photo

Production: Erin Suydam

Publicity: Jodi Price

Copyeditor: Jennifer Harris

This book has been composed in Arno Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Jacob Soll, Matt Kadane, and the future

CONTENTS

IMAGES

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

LET ME BEGIN with sadness. Two friends and mentors were sorely missed at the completion of this book: Joyce Appleby and Helli Koenigsbergerboth died in the period of its being written. I miss them.

Happily many debts were accumulated that can now be acknowledged: John Zammito, Geoffrey Symcox, Matt Kadane, Jake Soll, my graduate students, and as always my partner of thirty years, Lynn Hunt. All read, corrected, admonished, and generally made the life of researching and writing so much more rewarding than it might otherwise be. The wonders of the UCLA library and the University of California system can best be appreciated in the endnotes. The staffs of the History Department and the library are always efficient and kind. Various research assistants worked with alacrity, and I want to thank Paul Cella and Grace Ballor for being exceptionally helpful.

THE SECULAR ENLIGHTENMENT

Prologue

THE ENLIGHTENMENT was an eighteenth-century movement of ideas and practices that made the secular world its point of departure. It did not necessarily deny the meaning or emotional hold of religion, but it gradually shifted attention away from religious questions toward secular ones. By seeking answers in secular termseven to many religious questionsit vastly expanded the sphere of the secular, making it, for increasing numbers of educated people, a primary frame of reference. In the Western world, art, music, science, politics, and even the categories of space and time had undergone a gradual process of secularization in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries; the Enlightenment built on this process and made it into an international intellectual cause. By asserting this expansion of secularity, I do not mean to downplay the many religious manifestations found in the age. This book does not claim that religion was en route to being cast aside like bad bacteria waiting to be knocked out by an antibiotic of deism or atheism.

The chapters ahead do claim that attachment to the worldthe here and the nowto a life lived without constant reference to God, became increasingly commonplace and the source of an explosion of innovative thinking about society, government, and the economy, to mention but a few areas of inquiry. In attaching to the world, many people lost interest, or belief, in hell. Its proprietor, the devil, still haunted popular beliefs but was no longer invoked on a daily basis by the literate and educated.

Areas of human behavior once explained by concepts like miracles or original sin now received explanations inspired by physical science or the emerging studies of social and economic relations. Space and time were cleared of their Christian meaning, and people became more concerned with reorganizing the present and planning for the future than in their fate after death. They could enter churches not to pray but to admire the architecture, spend Sunday mornings reading a newspaper, cast a cold eye on clergy of every persuasion, and read risqu books to their hearts content. The secular-minded and literate could pursue their economic or commercial success, become innovative in science or technology, take up the liberal professions, work long hours in business or household, and imagine their successes or failures as the reward for their actions or the result of blind economic or social forces.

In a secular setting, the purpose of human life takes shape without necessary reference to a transcendent order; temporal well-being is the end being sought, now more readily managed by the increasing use of pocket watches. Where once the deeply religious monitored time to identify their shortcomings and assess their chances at salvation, the secular man lived a punctual life that found pleasure in work or social life. The secular woman, when not caring for home and domestic life, read novels, entertained in gatherings with an agendathe abolition of the slave trade, the news from France or Americaand died without fear of what might come next. Fathers and mothers sought to educate children so that they might find temporal happiness.

In this book, readers will hear a cacophony of rich voices new to the age. We will be introduced to freethinkers, low and high Anglican churchmen, Hobbes, Spinoza, Locke, Newton, moderate Scots Presbyterians, French materialists, Rousseauian idealists, pornographers, Lutheran pantheists, and deeply anticlerical Catholics. As a result of their writings about politics, society, or religion, after 1750 a new generation of Europeans and American colonists could imagine entirely human creations such as republics and democracies. So much of this creative energy occurred in citieshence the focus in many chapters on major urban settings. They did not cause the Enlightenment, but they facilitated its birthing.

Sometimes the signs of secularity, of living in the here and now, were subtle. Around the middle of the seventeenth century, Dutch professors of astronomy stopped teaching astrology. It was still widely practiced, yet, ever so gradually, in most annual Dutch almanacs its importance dwindled. About the same time, in the lifetime of Spinoza (d. 1677), few of his contemporaries could understand, let alone accept, his identification of God with Nature. Fast-forward to the 1780s in both England and Germany, where thinkers with obviously religious sentiments like the Lutheran Johann Herder, or the poet of Dissenting (non-Anglican, Protestant) background, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, could imagine a universe infused with the divine. In three generations, one of the foundations of Christian metaphysics, the absolute separation of Creator from Creation, of spirit from matter, had disaggregated.

The disaggregation could also be symbolic. A French masonic ceremony of the late 1770s occurred in its Sanctuary. There we find the throne of the master of the lodge and next to it on the altar three silver candlesticks, the book of statutes and rules of the lodge, the book of the gospel, a compass, a mallet, and in pride of place reposes, displayed, the new Constitutions from the Grand Orient of France. Were these masonic brothers in Strasbourg mocking the accoutrements of the Catholic Church? Or using them to signal the importance they attached to their legal status within the fraternity? The setting was adorned with sky-blue serge, braids and ribbons of gold, silver and jewels. It belonged to a lodge of merchants who lost little love for their aristocratic brothers largely found in other lodges. The orator of the occasion noted the bravery of the French soldiers fighting in the American Revolution. He also said that brothers meet under the living image of the Grand Architect of the Universe. Somewhere, in this mlange of symbols and talk about the Grand Architect, lurks the residue of the Christian heritage common to all the brothers, but did one of them actually have to believe in it? Readers can make up their own minds.

Next page