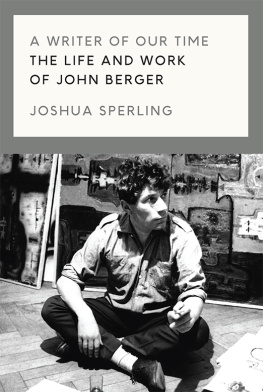

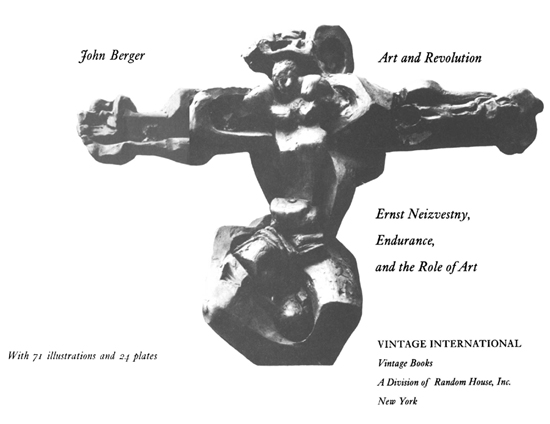

John Berger

Art and Revolution

John Berger was born in London in 1926. Art critic, novelist, and screenwriter, he is the author of many works of fiction and nonfiction, including About Looking, Ways of Seeing, Art and Revolution, and G., for which he won the Booker Prize. Most recently he has published To the Wedding and Photocopies. Berger lives in a small rural community in the French Alps.

Also by John Berger

Into Their Labours

(Pig Earth, Once in Europa, and Lilac and Flag: A Trilogy)

A Painter of Our Time

Permanent Red

The Foot of Clive

Corkers Freedom

A Fortunate Man

The Moment of Cubism and Other Essays

The Look of Things: Selected Essays and Articles

Ways of Seeing

Another Way of Telling

A Seventh Man

G.

About Looking

And Our Faces, My Heart, Brief as Photos

The Sense of Sight

The Success and Failure of Picasso

Keeping a Rendezvous

To the Wedding

Photocopies

First Vintage International Edition, December 1997

Copyright 1969by John Berger

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited Toronto. Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, in 1969.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Berger, John.

Art and revolution / John Berger.

p. cm.

Originally published: New York: Pantheon Books, 1969.

eISBN: 978-0-307-79431-4

I. Neizvestny Ernst. 1926 . 2. Socialism and artSoviet Union.

I. Title.

NB699.N4B4 1997

730.92dc21 97-8130

Random House Web address: http://www.randomhouse.com/

v3.1

To the memory of

I.D.

lucid teacher whom I read

now silent.

You might ask me as I ask myself why I have spent the last year working on a book about a Russian sculptor whom scarcely anyone outside Russia has heard of. And anyway, you say, how can I, the reader, judge the work of a sculptor solely by photographs, never having seen a single work by him?

Criticism is always a form of intervention: intervention between the work of art and its public. In most cases very little depends upon this intervention. Occasionally, however, criticism can be creative not so much by virtue of its quality of perception as by virtue of the circumstances upon which it may act. I believe this to be the case in writing now about Ernst Neizvestny. Not to have written this essay would have been a form of cowardice and negligence. Now that it is written I would make quite large claims for it.

By taking and considering in depth a particular example, it throws light on the character of Russian art, the situation of the visual artist today in the U.S.S.R., the meaning of politically revolutionary art and some of the future consequences of revolutionary consciousness. It is of course a short essay and in many directions it only tentatively suggests beginnings but they are beginnings, for little else has been written from a similar point of view on these subjects. The essay may have faults and weaknesses, but I would nevertheless put it forward as the best example I have achieved of what I consider to be the critical method.

I wish to make no competitive claim for the importance of Neizvestnys art. Obviously I consider his art important, or I would not have spent a year thinking and writing about it. Yet during that year I have come to see that the arranging of artists in a hierarchy of merit is an idle and essentially dilettante process. What matters are the needs which art answers.

J.B.

November 18, 1969

This book could not have been made without the interest and cooperation of Jean Mohr, who came with us to Moscow and took many photographs of Neizvestnys work. I would like to thank him very warmly. I would also like to thank Howard Daniel for encouragement, help in research, and the loan of innumerable books.

J.B.

Other acknowledgements are to:

Sir Kenneth Clark (for illustration onin the authors.)

Contents

1.

The month in which I am writing is June. On the eastern side of the Oder the wild lupins along the side of the main line to Moscow must be growing wildly and the wild acacias must be in full bloom. Trains in that landscape are like ships between small islands far from the mainland.

There are many fir plantations. The trees are planted in straight lines so that as the trains pass for those who are looking out of the window there is a strange optical effect as though the corridors between the trees were the traversing beams of light from an invisible lighthouse.

Do the images of the sea recur because this landscape is so far from the sea?

Often the bordering trees around the plantations are silver birches. From the train their silver trunks look as if they have been painted white to define the border.

The plantations give place to fields of wheat and of potatoes and grazing land, but mostly wheat. The wheat is high enough for you to lose your dog in. It is tawny like an animal, but tinged with green and around the skin of its ears with violet.

The sky is very big, the light is stretched across it stretched so that it gives the impression of having been worn thin. Dog-roses along the railway embankments look like mulberry stains on pale green linen such is the lack of definition, the endlessness, the edgelessness of the light of the plain.

A woman is watching her cow graze. A couple lie on the pale green linen grass. A cart is drawn by two horses along a straight uneven road. A man bends over some vegetables to see whether they can be picked today. A cyclist appears like a moving post on the far side of the wheat.

The Bug is a smaller river than the Oder. But having crossed it, you are in Russia. People sit in the grass along the edge of the railway as if it were a river or a canal. The colours of their summer clothes are bright and papery like the colour of bus tickets.

In a street behind the Byelorussian station there is certainly a woman in a white overall and with a kerchief keeping her hair out of her hot face who is selling kvas from a large barrel-like tank on wheels. Kvas is made from black bread and water and yeast, left briefly to ferment together. It is the colour of damp cardboard. Long after you have drunk it, the taste clings to the top of your palate: the taste of bread, summer, the flat plain and the quenching of thirst.

It is the time of year when the courtyards of Moscow lend the city a fourth dimension. There are tens or hundreds of thousands of these courtyards. They are not like gardens or parks.

As two women hang up their washing they talk. There is tall grass around them and against the sky the thick foliage of trees. The earth and dust underfoot is mysteriously of the countryside: like the earth of a well-trodden footpath to a village railway station. The women are dressed like peasants. When one of them has hung up her basketful of washing, she sits down on a wooden bench by a wooden fence and stretches her legs straight out in front of her as though she were on a toboggan.