THE HISTORY OF ENGLAND

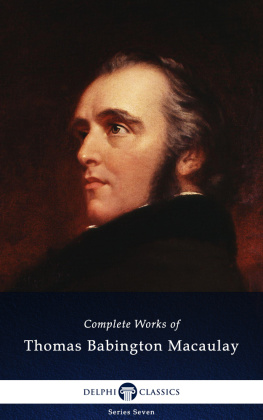

T HOMAS B ABINGTON M ACAULAY was born in Leicestershire in 1800, the son of Zachary Macaulay, the philanthropist and reformer. He studied at Trinity College, Cambridge, and in 1825 published a long essay on Milton in the Edinburgh Review which revealed his strong Whig sympathies and brought him instant notice. During the next twenty years he continued to write numerous articles on historical and literary topics for the Review. In 1830 he entered Parliament as a member of the Whig party and made a strong speech in support of the Reform Bill of 1831. In 1834 Macaulay accepted a place on the newly created supreme council for India and had a decisive influence on the Indian educational system and code of law. On his return to England in 1838 he was elected MP for Edinburgh and was also Secretary at War from 1839 to 1841. During this period he wrote two of his most widely published essays, on Robert Clive and Warren Hastings, which were inspired by his experiences in India. In 1842 he published a highly acclaimed volume of his poetry entitled Lays of Ancient Rome. His collected Essays Critical and Historical appeared a year later and was equally well-received. Macaulay became Paymaster General in 1846 but lost his seat and his office in the General Election of 1847. In 1852 he was re-elected MP for Edinburgh. Throughout these years he sought to detach himself from politics, wishing to devote all his time to writing, and he finally retired from Parliament in 1856. The first volumes of The History of England appeared in 1849 and were an instant success. A further two volumes were published in 1855. His reputation was now world-wide and his works had been translated into many languages. However, his health deteriorated and he never completed his History although a fifth volume was published posthumously in 1861. Macaulay was raised to the peerage in 1857. He died in 1859 and was buried in Westminster Abbey.

H UGH T REVOR -R OPER (Lord Dacre of Glanton) was Regius Professor of Modern History at Oxford from 1957 to 1980 and Master of Peterhouse, Cambridge, from 1980 to 1987. He published his first book, Archbishop Laud, in 1940; in 1947 he published The Last Days of Hitler, an immediate bestseller. His other books include Religion, the Reformation and Social Change (1967), The Philby Affair (1968), The European Witch-Craze of the 16th and 17th Centuries (1970), Princes and Artists (1976), Hermit of Peking: The Hidden Life of Sir Edmund Backhouse (1976, originally published as A Hidden Life), The Goebbels Diaries (1978), Renaissance Essays (1985), Catholics, Anglicans and Puritans (1987) and From Counter-Reformation to Glorious Revolution (1992).

LORD MACAULAY

The History of England

EDITED AND ABRIDGED

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY

HUGH TREVOR-ROPER

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Putnam Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

Penguin Books India (P) Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Books (NZ) Ltd, Cnr Rosedale and Airborne Roads, Albany, Auckland, New Zealand

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London, WC2R 0RL, England

www.penguin.com

First published 18481861

This selection first published in the United States of America by the Washington Square Press 1968

Published in the Penguin English Library 1979

Reprinted in Penguin Classics 1986

This edition copyright Washington Square Press, Inc., 1968

All rights reserved

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

ISBN: 978-0-14-196123-1

Lord Macaulay: Introduction

WHIG HISTORY

L ORD M ACAULAY is unquestionably the greatest of the whig historians. By the clarifying brilliance of his style, and his compelling gift of narrative, he won an instant and apparently effortless success in the nineteenth century. The interpretation of English history which he gave became the standard interpretation for nearly a century: so universally accepted that we hardly realize the novelty which it once contained. Admittedly, that interpretation has now become unfashionable. But it can never be altogether rejected. Much of it both in factual scholarship and in general interpretation has become part of the permanent acquisition of historical science. The severest critics themselves are generally unaware of the extent to which they depend on the achievement of their victim. In order to appreciate that debt, it will be useful to begin by considering the interpretation of English history before Macaulay stamped it, indelibly, with his imprint.

For whig history is essentially English. In its crudest form it is the interpretation imposed on the English past by an English political party in search, at the same time, of both a historical pedigree and a political justification. This is not to deny that the thesis may also be true, or that it may also be applicable to other countries. In fact, the whig theory of history has foreign as well as English origins. It owes much to the French Huguenots and even more (including the name whig) to the Scots. There are Continental historians the French Protestant statesman-historian F. P. G. Guizot is an obvious example who can be described as whigs. But it is in England that the continuous whig party was developed and in England that the consistent whig theory of history was elaborated. It was also to English history that it was most naturally applied. A whig interpretation of Europe is conceivable; but it could never be expressed with Macaulays brilliant clarity. The pattern would not admit the simple antitheses which are possible, and perhaps justified, in the special English circumstances. Macaulay himself was well aware of this. He was, he once wrote, as much puzzled as pleased by the success of his History abroad, for the book is quite insular in spirit. There is nothing cosmopolitan about it

Whig history, then, is insular history. It is also Protestant history. Indeed, its Protestantism is inseparable, in origin, from its insularity: for it was the revolt from Rome, in the sixteenth century, which caused historians not only in England or Scotland to look for a national history, independent of that universal Roman Church which had been served and extolled by the monkish chroniclers of the past. But these earliest national, Protestant historians, if they had dissociated the history of their countries from foreign despotism, had not, at that time, supplied it with any secular ideology. If they were Protestant, they were not yet republican or whig. In some countries they might be. In France, for instance, the Huguenot writers soon discovered that national Protestantism could only be secured in opposition to the Valois monarchy; and so, after the Massacre of St Bartholomew in 1572, they discovered that the ancient constitution of France was not monarchical but oligarchical. The same discovery was made in Scotland, after the deposition of Mary Queen of Scots. Buchanans

Next page