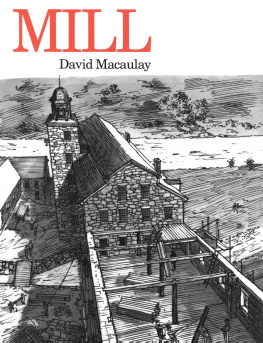

David Macaulay - Mill

Here you can read online David Macaulay - Mill full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1983, publisher: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Mill

- Author:

- Publisher:Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

- Genre:

- Year:1983

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Mill: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Mill" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Mill — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Mill" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Copyright 1983 by David Macaulay

All rights reserved. For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

www.hmhco.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Macaulay, David.

Mill.

1. Textile factoriesRhode IslandHistory. I. Title.

TS1324.R4M33 1983 677'.009745 83-10652

RNF ISBN 978-0-395-34830-7

PAP ISBN 978-0-395-52019-2

eISBN 978-0-547-34836-0

v3.0816

This book would have been far more difficult to write and significantly less completewithout the advice and expertise of several people. For their interest and generosity Iwould like to thank the following:

Patrick M. Malone at the Slater Mill Historic Site, who withstood seven readings ofthe manuscript.

Theodore Z. Penn of Old Sturbridge Village, particularly for his help on powertransmission.

Thomas Leary, for his patience.

John Chaney, for his first-hand knowledge of the nineteenth century.

Myron Stachiw, Charles Parrott, Jack Lozier, Helena Wright, Betsy Bahr, SarahGleason, Richard Greenwood, Elizabeth Sholes, Jeff Howry, and Ruth Macaulay, towhom, for her editorial assistance and extraordinary tolerance, this book is lovinglydedicated.

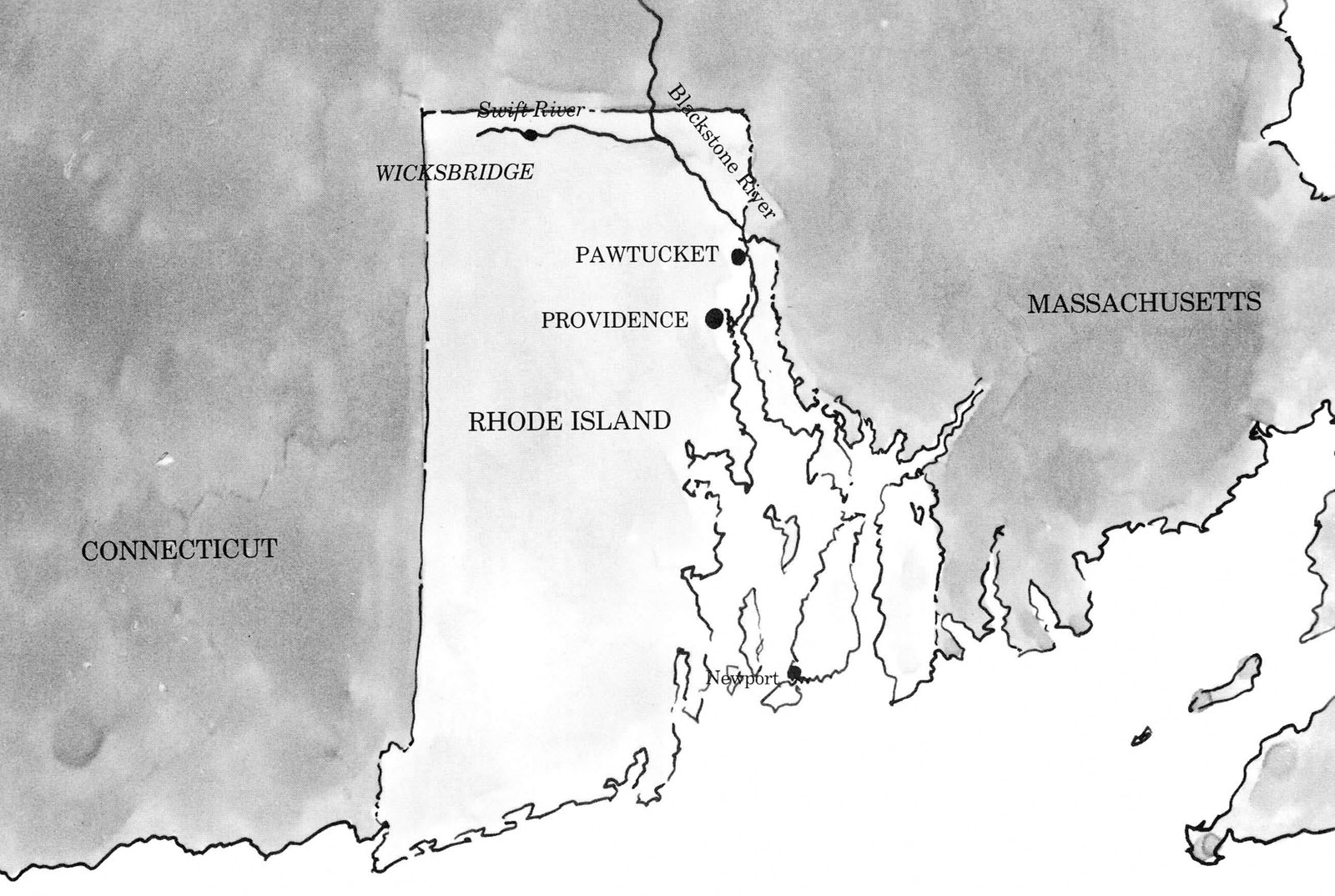

The mills of Wicksbridge are imaginary, but their planning, construction, and operation are typical of those developed throughout New England during the nineteenth century.

Each New England mill is an architectural statement of the financial resources and ambitions of its owners. The permanence and often remarkable state of preservation of these mills are a tribute to the ingenuity and hard work of their builders. The number and density of communities that grew up around the mills still recall the lure of financial independence and personal prosperity that these structures once symbolized. In their physical domination of the surrounding landscape, however, many mills continue to remind us that no opportunity comes without a price.

Cotton must first be spun into yarn before it can be woven into cloth. For centuries this was done by hand in the home. After being cleaned and prepared, the individual fibers were carefully drawn and twisted into a continuous thin strand and wound around a spindle. The spun yarn was then transferred to looms, on which it was woven into fabric.

The mechanization of spinning and weaving, which resulted in the creation of the textile industry, was part of an unprecedented period of technological invention known as the Industrial Revolution. It began in England in the middle of the eighteenth century and continued well into the nineteenth century in Europe and the United States.

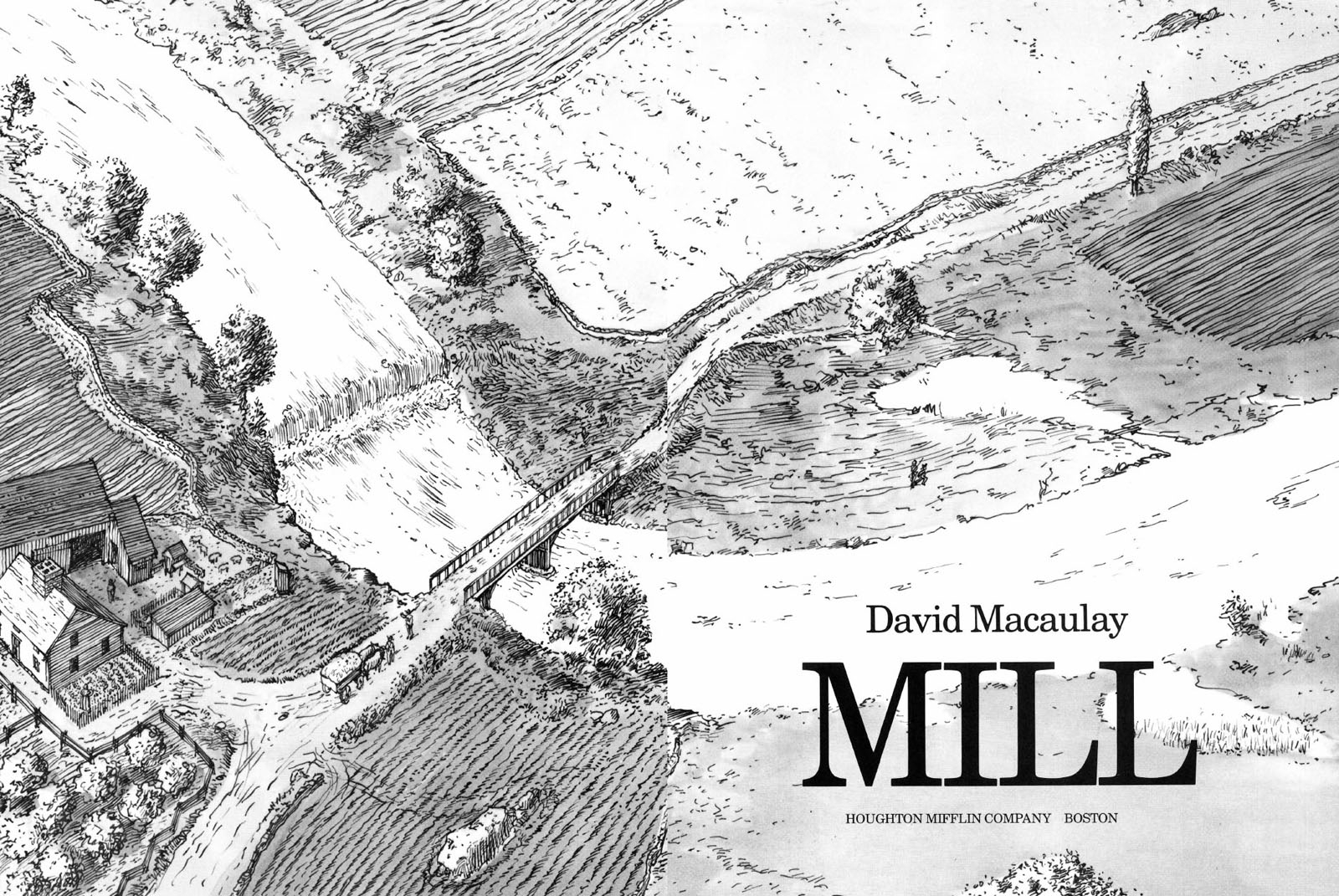

A new kind of building was designed to house great numbers of these new machines so they could all be run from a central power source. Long, narrow, multistoried structures, some using water wheels, others steam engines, were built in both England and Scotland. They were called either manufactories or mills.

These mills spawned an increase in production that brought with it the need to find new markets and to protect old ones. As the prime exporter of textiles to Europe and North America, Great Britain jealously guarded any new developments in either machinery or manufacture that might encourage others to compete. A shortage of technical expertise along with an abundant supply of imported cloth did little to encourage the development of Americas own textile industry.

However, in the fourth quarter of the eighteenth century things began to change. Not only did the United States win political independence, but a growing number of Americans wanted greater economic independence. British immigrants familiar with the textile industry were welcomed along with their knowledge, and by 1793 a recent arrival named Samuel Slater had built and was operating Americas first successful cotton spinning mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, using the water power of the Blackstone River.

While spinning cotton with water-powered machinery was unknown in America before the 1790s, the use of water power for a variety of other tasks had been well established. Almost every New England river and stream of any size had at least one mill, usually more.

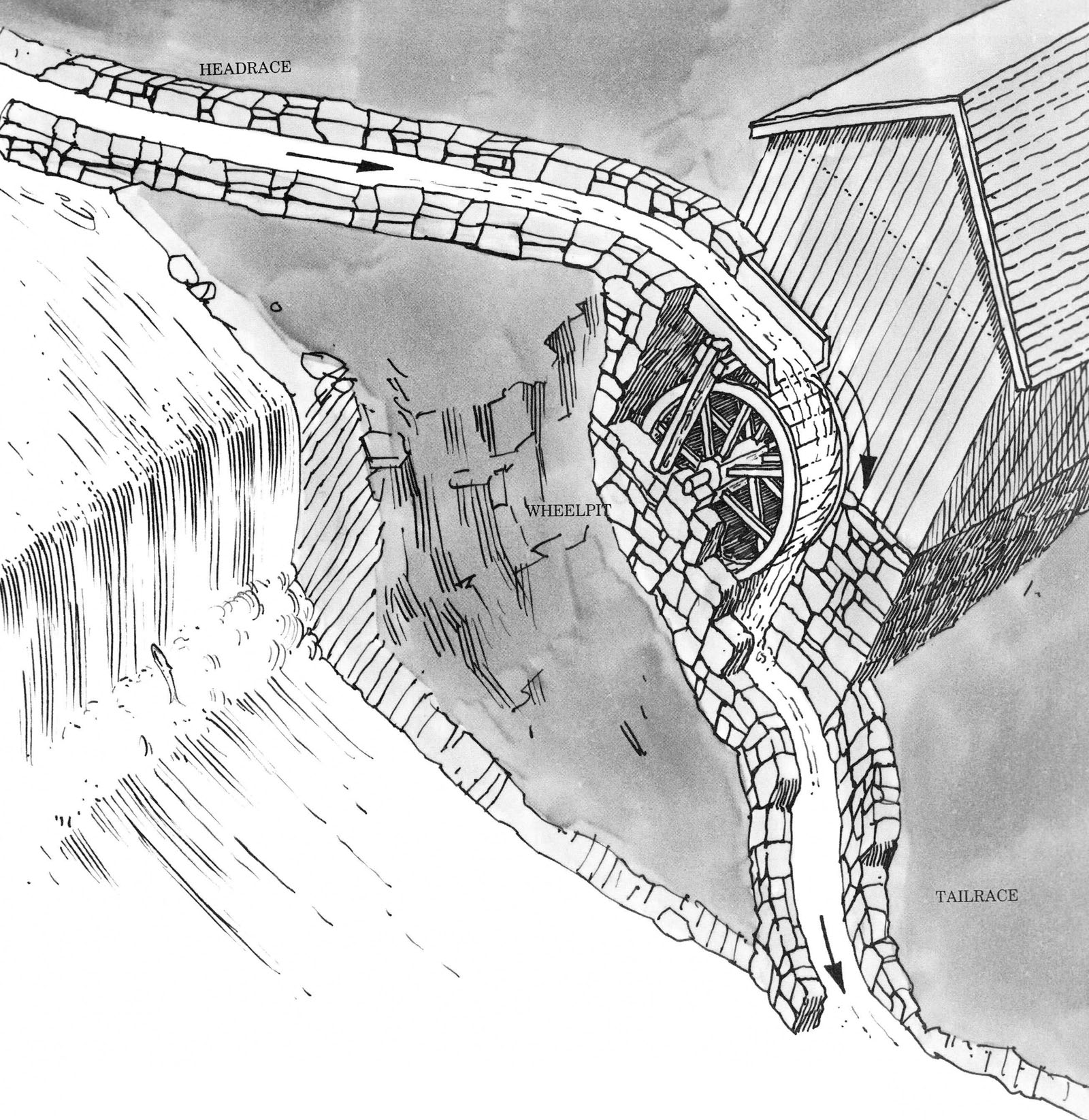

By 1800, a saw mill, a fulling mill, and a grist mill, all powered by water wheels, stood near a waterfall on the Swift River, a tributary of the Blackstone fifteen miles north of Pawtucket. Each wheel turned in its own stone-lined enclosure called a wheelpit, and each wheelpit was linked to the river by a channel called a raceway. The portion of the raceway that delivered water to the wheel was called the headrace; the portion that returned it to the river after it had turned the wheel was called the tailrace.

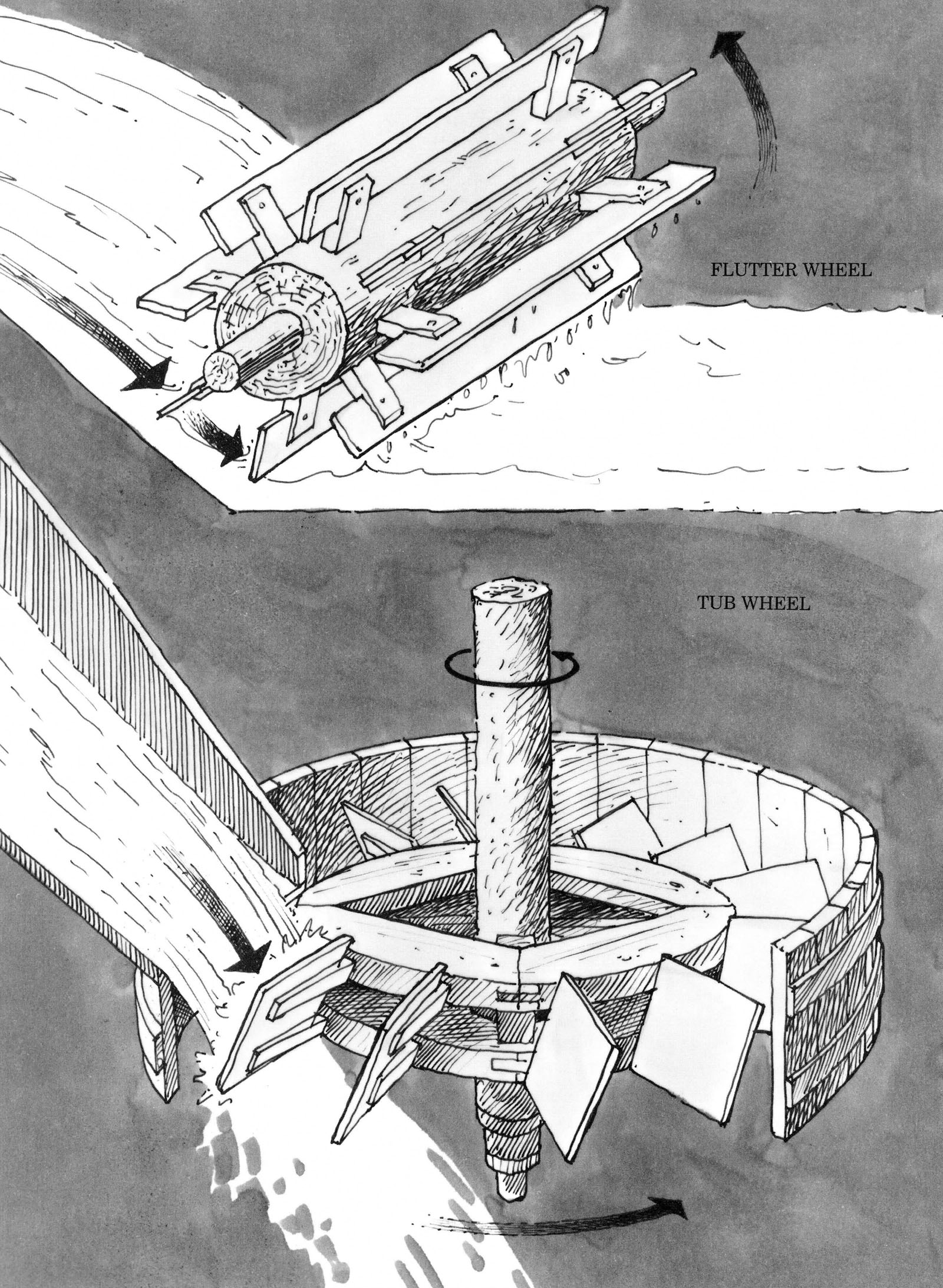

The saw mill contained two water wheels. The first, called a flutter wheel, operated the up-and-down saw while driving the log into the blade. The flutter wheel was basically a horizontal shaft from which radiated a number of boards called blades. It turned as the water passing underneath it pushed the blades.

The second wheel was a tub wheel. It powered the machinery that withdrew the log once it had been cut. It, too, was turned by the force of the water against its blades. In this case, however, the blades were attached to a vertical shaft and enclosed by a round wooden tub.

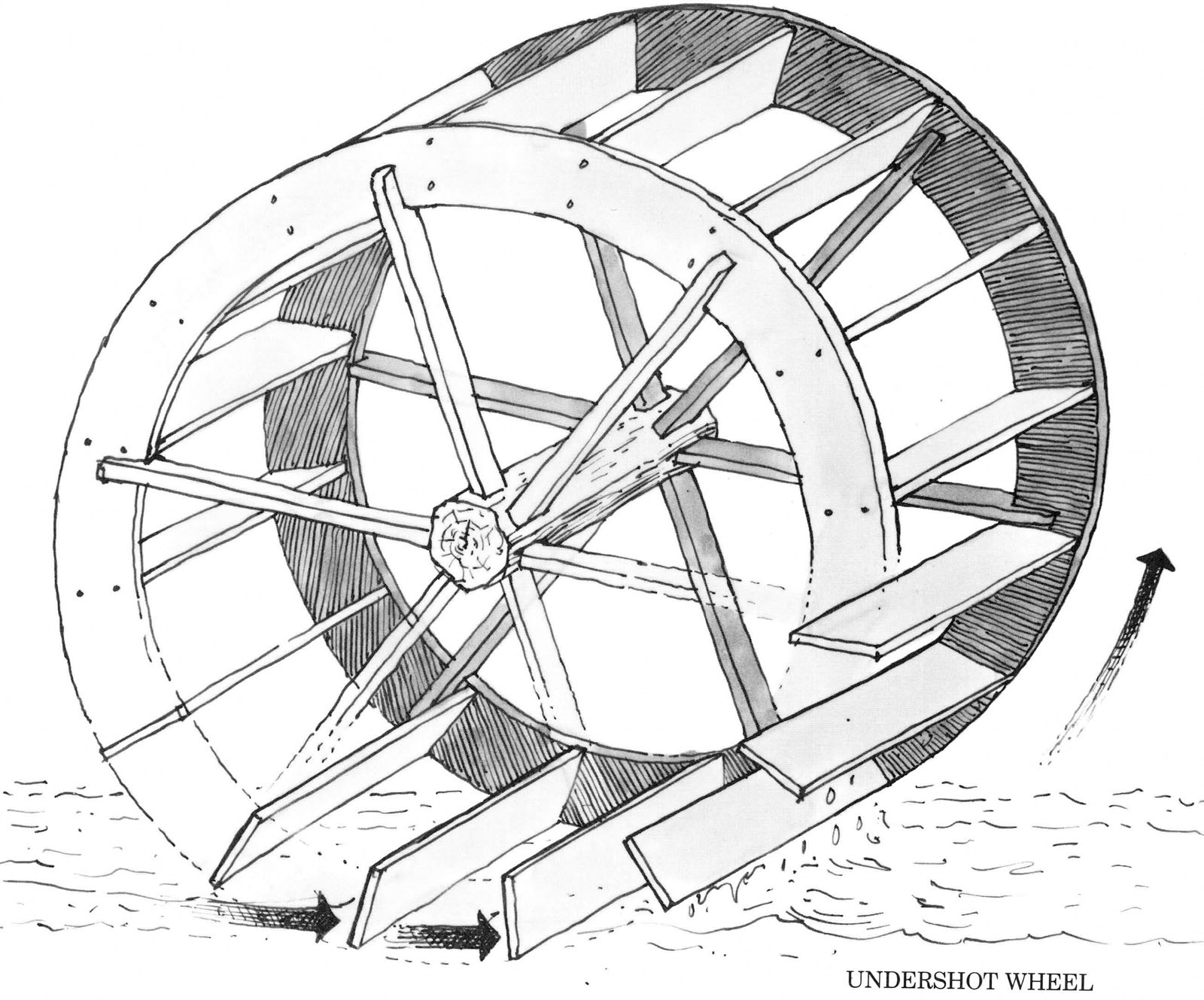

In the fulling mill, woolen cloth woven by local families was pounded by wooden hammers to clean and thicken it. The hammers were powered by an undershot wheel. Although much larger than the flutter wheel, it was also turned by the force of the water flowing under it and striking its blades.

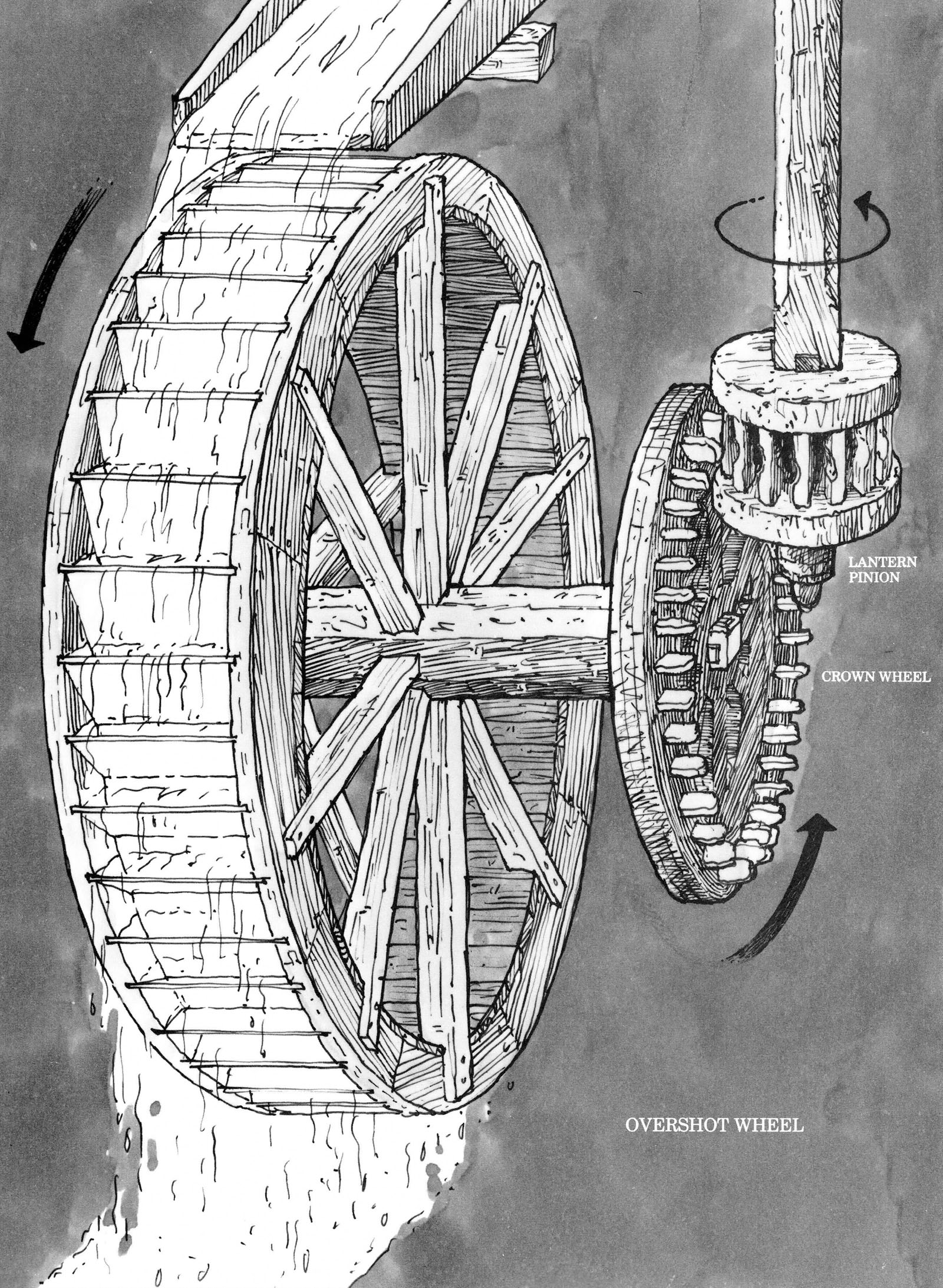

The grist mill ground corn and wheat for many of the areas farmers. It was powered by a large overshot wheel. Instead of having blades, the perimeter of the overshot wheel was constructed with a continuous row of wooden troughs called buckets. Water from the headrace poured over the top of the wheel and into the buckets. The weight of the water in the buckets turned the wheel.

The vertical distance the water drops between headrace and tailrace is called the head. The amount of power available at any site was dependent on both the head and the rate of flow.

When the equipment in a mill couldnt be run directly from the shaft of the water wheel, a system of gears, additional shafts, pulleys, and belts called a power train was required. In the grist mill, the shaft of the wheel extended beyond the wheelpit and into the space below the first floor. A flat wooden wheel called a crown wheel was attached to this extension. A circle of wooden cogs projected from one side of the crown wheel near its rim. They meshed with and turned a cylindrical, wooden, cage-like structure called a lantern pinion. This gear revolved on a vertical shaft that was connected through two additional gears and a smaller shaft to the upper millstone. Because the diameter of the lantern pinion was only one quarter that of the circle of cogs, it turned four times for each revolution of the crown wheel. By going from larger to smaller gears in this way the millstone could be turned over a hundred times every minute while the water wheel turned only seven.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

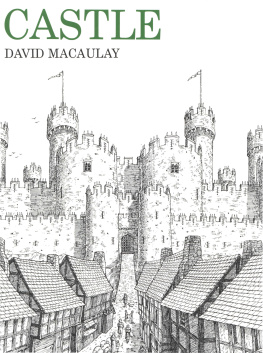

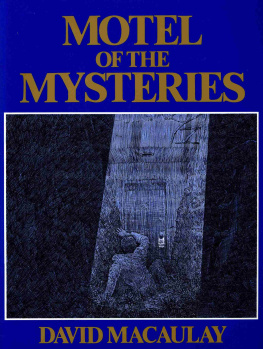

Similar books «Mill»

Look at similar books to Mill. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Mill and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.