NEW MERMAIDS

General Editors:

William C. Carroll, Boston University

Brian Gibbons, University of Mnster

Tiffany Stern, University of Oxford

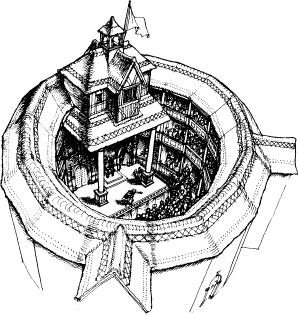

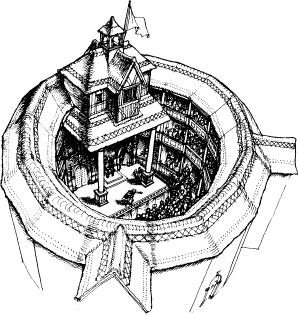

Reconstruction of an Elizabethan Theatre

by C. Walter Hodges

NEW MERMAIDS

The Alchemist | The Man of Mode |

All for Love | Marriage A-La-Mode |

Arden of Faversham | Mrs Warrens Profession |

Arms and the Man | A New Way to Pay Old Debts |

Bartholmew Fair | The Old Wifes Tale |

The Beaux Stratagem | The Playboy of the Western World |

The Beggars Opera | The Provoked Wife |

The Changeling | Pygmalion |

A Chaste Maid in Cheapside | The Recruiting Officer |

The Country Wife | The Relapse |

The Critic | The Revengers Tragedy |

Doctor Faustus | The Rivals |

The Duchess of Malfi | The Roaring Girl |

The Dutch Courtesan | The Rover |

Eastward Ho! | Saint Joan |

Edward II | The School for Scandal |

Elizabethan and Jacobean Tragedies | She Stoops to Conquer |

Epicoene or The Silent Woman | The Shoemakers Holiday |

Every Man In His Humour | The Spanish Tragedy |

Four Revenge Tragedies | Tamburlaine |

The Spanish Tragedy | The Tamer Tamed |

The Revengers Tragedy | Three Late Medieval Morality Plays |

Tis Pity Shes a Whore | Mankind |

The White Devil | Everyman |

Gammer Gurtons Needle | Mundus et Infans |

An Ideal Husband | Tis Pity Shes a Whore |

The Importance of Being Earnest | The Tragedy of Mariam |

The Jew of Malta | Volpone |

The Knight of the Burning Pestle | The Way of the World |

Lady Windermeres Fan | The White Devil |

London Assurance | The Witch |

Love for Love | The Witch of Edmonton |

Major Barbara | A Woman Killed with Kindness |

The Malcontent | A Woman of No Importance |

Women Beware Women |

NEW MERMAIDS

CHRISTOPHER MARLOWE

EDWARD II

Edited by Martin Wiggins

Fellow of the Shakespeare Institute

University of Birmingham

Text edited by Robert Lindsey

Revised with a new introduction

by Stephen Guy-Bray

University of British Columbia

CONTENTS

The Introduction to this revised edition is the work of Stephen Guy-Bray; the text and commentary were prepared for the original edition by Robert Lindsey and Martin Wiggins in collaboration.

I am grateful to Tiffany Stern for asking me to write the introduction to this new edition of Edward II. It has been a very interesting and rewarding project. At Bloomsbury, I thank Margaret Bartley, Claire Cooper, Simon Trussler, and Margaret Berrill for all their help and hard work. My colleague Vin Nardizzi read the first draft of the introduction and made many helpful comments, many of which I actually followed. And I thank Julie Beebe for giving me such a wonderful place to write.

STEPHEN GUY-BRAY

Our paramount debt is to the General Editor, Brian Gibbons, whose painstaking and exacting work has significantly improved the edition, especially in matters on which we ultimately had to agree to differ. In the early stages of preparing the edition, Dr L.G. Black gave valuable advice and guidance, Simon Markham made useful suggestions on the text and notes, and Roma Gill gave both encouragement and the benefit of her knowledge and experience. In the later stages, we have further benefited from the textual expertise of John Jowett and the wisdom of Stanley Wells. We have been fortunate in dealing with librarians and archivists who fully understand the needs of the researcher, particularly Susan Brock of the Shakespeare Institute library, Stratford-upon-Avon; James Shaw of the Shakespeare Centre Library, Stratford-upon-Avon; Susan Knowles of the BBC Written Archives Centre, Caversham; and Richard Bell of the Bodleian Library, Oxford. Among postgraduate students, Rebekah Owens shared the results of her research on Kyds letter to Puckering, and Solitaire Townsend, Shaalu Malhotra, and Sue Taylor all helped to locate material relating to the stage history. Paul Edmondson, Jeremy Ehrlich, Eugene Giddens, Mary McGuigan, and especially Jane Kingsley-Smith made an invaluable contribution to the proof-checking. At A. & C. Black, Anne Watts has been a supportive and sympathetic editor, and we could not have hoped for a better job of copy-editing than we received from Margaret Berrill. Others who have helped in various ways, great and small, are Kelley Costigan, Lorna Flint, Andrew Pixley, Trefor Stockwell, Keith Topping, and The Malone Society.

MARTIN WIGGINS AND ROBERT LINDSEY

Christopher Marlowe has been a highly regarded and highly controversial writer since he first became famous in the mid-1580s as the author of Tamburlaine. While Doctor Faustus is probably still his most famous play, Edward II has become increasingly popular and increasingly widely studied in the last few decades. This is for a number of reasons. For one, as a history play Edward II provides a usefully different approach to the question of the representation of English history from that of Shakespeares plays. While Shakespeares history plays, broadly speaking, rely on an attitude toward kingship that is never really interrogated, Marlowes play his sole history play calls into question the nature of English kingship itself. In this respect, Edward II makes an interesting pair with Shakespeares Richard II, which also tells the story of a weak king, although this comparison will show the extent to which Marlowes critique of monarchy is more thorough than Shakespeares.

Edward II has also been of tremendous importance in the field of sexuality studies, an area that has become one of the most important fields within Renaissance literary studies over the course of the last thirty years or so. It has long been recognized that much Renaissance literature interrogates traditional ideas about gender roles and about the forms of sexual expression deemed permissible or impermissible in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, but in many of the texts studied from this point of view the comedies of Shakespeare and Lyly are an obvious example the theme of sexual transgression is treated with some caution and the texts in question usually end with the reemergence of the traditional sexual order.

Edward I banished Piers Gaveston, his sons lover, from England. As the play opens, Edward I has just died; the new king, Edward II, has called Gaveston back from France. While the two men are overjoyed at being reunited, their attachment is viewed with increasing disfavour by Edwards wife Isabella and by a powerful group of nobles, led by the Mortimers (younger and older) and the Earl of Lancaster. The nobles succeed in getting Gaveston banished but, on the advice of the queen, they recall him so as to have him under their control. After a series of skirmishes and pursuits, the nobles capture and execute Gaveston. Before long, Edward II finds a new lover (Spencer the younger) and civil war begins again. The queen and her lover the younger Mortimer defeat Edward and take him captive. Mortimer orders Edward killed and rules England through the queen. At the very end of the play, however, Edwards young son, now Edward III, takes control of his kingdom and orders the execution of Mortimer and the imprisonment of Isabella. The play ends with the tableau of Mortimers head on Edward IIs coffin.

Next page