Introduction

WHEREVER PEOPLE CAN read, there are stories about the magic, mystery, and power of what they read. Because reading unlocks knowledge and power, people hoard it and fight for it just as they fight for treasures and gold.

he ancient Romans told a tale about one of their kings, Tarquin, who wanted to know what fate had in store for his kingdom so that he could be a better, stronger ruler. He went to see the Sibyl of Cumae, a wise woman who lived in a cave, to ask her to read the future. As the king approached the dark cavern, the old woman looked up from where she huddled by a fire and told him that all the future was written in her own nine books of prophecy. She said she would sell these books to him for a very high price.

he ancient Romans told a tale about one of their kings, Tarquin, who wanted to know what fate had in store for his kingdom so that he could be a better, stronger ruler. He went to see the Sibyl of Cumae, a wise woman who lived in a cave, to ask her to read the future. As the king approached the dark cavern, the old woman looked up from where she huddled by a fire and told him that all the future was written in her own nine books of prophecy. She said she would sell these books to him for a very high price.

King Tarquin laughed angrily at the outrageous amount. Ridiculous, he said. Id never pay that.

Very well, said the Sibyl. She threw three of her nine books into the fire.

But what part of the future was that? said the alarmed king.

Whatever it was, it is now unknowable, the Sibyl replied. Do you want the other six books?

This version of the Sibyl of Cumae was painted in the early 1600s by Domenico Zampieri, an artist who worked mostly in Rome and Naples. The sybils cave overlooked the ancient town of Cumae, which lies between the two cities.

Thats why I came to see you, said Tarquin, What is the price for six? The Sibyl said, The same price. Again the king shook his head, so she picked up three more books and tossed them into the flames as well. These visions too are now lost, she told him.

The king was horrified by the destruction. Was she mad? Would she burn all these precious books? He ordered his servant to bring his purse and he emptied it on the cave floor, paying the sum that, at the beginning, would have bought him all nine volumes. With a shrug the Sibyl gave him her last three books. Carefully the king carried them back to Rome, where he ordered them housed in a splendid building, to be consulted by the Senate on Romes most momentous occasions.

In our own times, we too have stories about the power of books. Sometimes they are about the struggle to learn to read; sometimes they are about defying people who want to prevent others from reading.

Another tale is of the sorcerers apprentice theres a version of it in the movie Fantasia (Mickey Mouse plays the apprentice). It tells of a junior wizard who works hard carrying buckets of water for his magician master. The master wont let his apprentice see his book of spells. He tells the student to concentrate on his chores. One day, the magician goes away. Of course, the student goes straight to the forbidden book. He finds a spell to enchant a broom so that it will bring a bucket of water for him. When that works, the happy apprentice reads more spells and creates many brooms, all carrying pails of water. But the brooms wont stop bringing water, and soon the apprentice realizes that he is going to drown in the magic pouring out of the book. He is only saved when the magician comes back, casts a new spell, and slams the book shut.

There are stories about the power of magical texts in the Bibles Book of Revelation, in Shakespeares play The Tempest, in The Arabian Nights, in J.R.R. Tolkiens The Lord of the Rings, and in J.K. Rowlings Harry Potter stories. In C.S. Lewiss The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, a girl named Lucy opens a magicians book because she wants to help her friends escape his spells, and she finds enchantments both dangerous and wonderful.

What do all these stories have in common?

The ancient idea that writing contains power, and that reading unlocks that power.

This book you are looking at right now is a history of reading. But it is also about people who have been denied the power of reading. Its about lost writing, forbidden books, mistranslations, codes, and vanished libraries. Its about censors, vandals, and spies. Its about people who write in secret. And its about people who devote their hearts and brains to learning what has been written.

The First Readers

The First ReadersIN ANCIENT TIMES , the precious skill of reading was reserved for rulers and priests only. But the secret wasnt always theirs to keep.

n summer in the Mesopotamian plain what we now call Iraq the sun beats down like a drum. More than four thousand years ago, it beat down on one of the worlds first great cities, Ur, not far from where Baghdad is today. It shone on Urs people, tens of thousands of them, all the subjects of King Sargon. As they groaned and sweated through the labor of the day, they surely found the heat unbearable. But they left no words of complaint because they didnt have the skills to put their thoughts into writing. There were people in Ur who could do that, however. Looking down on these workers from the temple walls and palace towers were scribes and priests and priestesses who, for the first time in human history, could read and write.

n summer in the Mesopotamian plain what we now call Iraq the sun beats down like a drum. More than four thousand years ago, it beat down on one of the worlds first great cities, Ur, not far from where Baghdad is today. It shone on Urs people, tens of thousands of them, all the subjects of King Sargon. As they groaned and sweated through the labor of the day, they surely found the heat unbearable. But they left no words of complaint because they didnt have the skills to put their thoughts into writing. There were people in Ur who could do that, however. Looking down on these workers from the temple walls and palace towers were scribes and priests and priestesses who, for the first time in human history, could read and write.

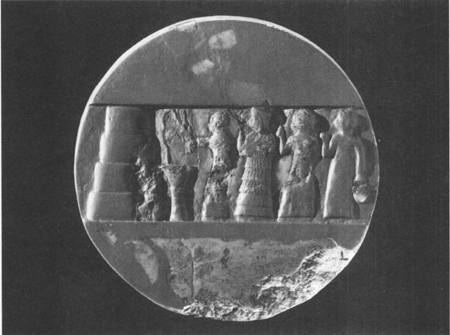

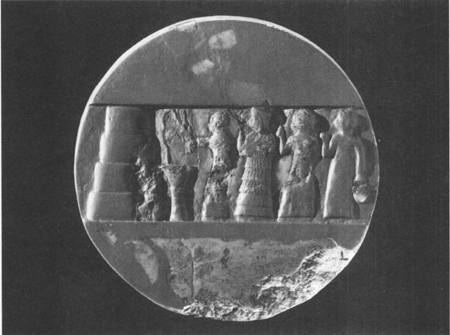

People had been making marks to keep track of what they produced, owned, and traded even before the time of Ur. Over centuries, these marks grew more complex: drawings of wine jugs and swords, sheep and slaves. But it was in Mesopotamia, around 4,300 years ago, that a few priests, merchants, and royal servants started to simplify picture drawings into something like an alphabet. And it was in Mesopotamia that these readers and writers created some of the worlds first works of literature poems and epic stories such as the Epic of Gilgamesh, and the Bibles story of Genesis: how Abraham left his home in Ur for the land of Canaan. Among the earliest of works from Ur are hymns written in honor of Inana, goddess of love and war.

Imagine Ur in those days. The city streets are like an oven, but its cooler in the shade of the Giparu, a complex of temples and the official home of the En, or high priestess. Inside the Giparu, with her head bowed and her eyes cast down, a servant girl silently pads across the floor in her bare feet to wait on En-hedu-anna (En = high priestess, hedu = ornament, and anna = of the Sky God).

he ancient Romans told a tale about one of their kings, Tarquin, who wanted to know what fate had in store for his kingdom so that he could be a better, stronger ruler. He went to see the Sibyl of Cumae, a wise woman who lived in a cave, to ask her to read the future. As the king approached the dark cavern, the old woman looked up from where she huddled by a fire and told him that all the future was written in her own nine books of prophecy. She said she would sell these books to him for a very high price.

he ancient Romans told a tale about one of their kings, Tarquin, who wanted to know what fate had in store for his kingdom so that he could be a better, stronger ruler. He went to see the Sibyl of Cumae, a wise woman who lived in a cave, to ask her to read the future. As the king approached the dark cavern, the old woman looked up from where she huddled by a fire and told him that all the future was written in her own nine books of prophecy. She said she would sell these books to him for a very high price.

n summer in the Mesopotamian plain what we now call Iraq the sun beats down like a drum. More than four thousand years ago, it beat down on one of the worlds first great cities, Ur, not far from where Baghdad is today. It shone on Urs people, tens of thousands of them, all the subjects of King Sargon. As they groaned and sweated through the labor of the day, they surely found the heat unbearable. But they left no words of complaint because they didnt have the skills to put their thoughts into writing. There were people in Ur who could do that, however. Looking down on these workers from the temple walls and palace towers were scribes and priests and priestesses who, for the first time in human history, could read and write.

n summer in the Mesopotamian plain what we now call Iraq the sun beats down like a drum. More than four thousand years ago, it beat down on one of the worlds first great cities, Ur, not far from where Baghdad is today. It shone on Urs people, tens of thousands of them, all the subjects of King Sargon. As they groaned and sweated through the labor of the day, they surely found the heat unbearable. But they left no words of complaint because they didnt have the skills to put their thoughts into writing. There were people in Ur who could do that, however. Looking down on these workers from the temple walls and palace towers were scribes and priests and priestesses who, for the first time in human history, could read and write.