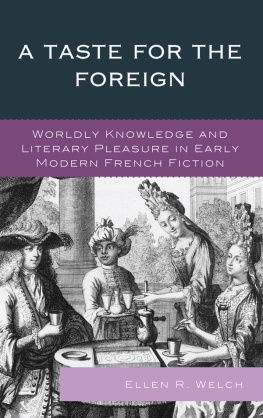

A Taste for the Foreign

A Taste for the Foreign

Worldly Knowledge and Literary

Pleasure in Early Modern French Fiction

Ellen R. Welch

University of Delaware Press

Newark

Published by University of Delaware Press

Co-published with The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rlpgbooks.com

Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom

Copyright 2011 by Ellen R. Welch

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available

Welch, Ellen R.

A taste for the foreign : worldly knowledge and literary pleasure in early modern French fiction / Ellen R. Welch.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-61149-062-6 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-61149-063-3 (electronic)

1. French literature 16th century History and criticism. 2. Exoticism in literature. 3. French literature 17th century History and criticism. 4. National characteristics, French, in literature. 5. French literature 18th century History and criticism. 6. Literature and globalization France History. I. Title.

PQ145.7.A2W45 2011

843'.40911 dc22

2010053746

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992

Printed in the United States of America

At the beginning of a book that explores the intersection between knowledge and pleasure, it is a privilege to be able to thank the many people who made researching it a joy. First and foremost, I thank Joan DeJean, who nurtured this project from its earliest stages and provided unflagging support and encouragement throughout its development. I can only strive to follow her example of scholarly passion, generosity, and high intellectual standards. No one could wish for a better mentor. The advice and insights of Lance Donaldson-Evans and Roger Chartier made this project richer and broader. Barbara Fuchs, Gerald Prince, and Bethany Wiggin influenced the shape of my thinking more than they probably realize. Tom DiPiero offered transformative comments on one chapter. Sahar Amer, Hassan Melehy, and Roland Racevskis helped me articulate the aims of this final incarnation of the project. Two anonymous readers for the University of Delaware Press helped refine it with their perceptive criticisms. My arguments have also benefited from the questions and remakrs of countless colleagues who listened to parts of this project at meetings of the North American Society for Seventeenth-Century French Literature, the Society for Interdisciplinary Studies on the Seventeenth Century, the Group for Early Modern Cultural Studies, and the American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies. I am grateful to John Pollock for answering all kinds of unexpected questions. Juan Carlos Gonzlez Espitia generously shared his editorial insights.

An earlier version of part of chapter 3 appeared previously as Cultural Capital: Paris, Cosmopolitanism and the Novel in Jean de Prchacs LIllustre Parisienne, Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies 9, no. 2 (2009):124. I thank Indiana University Press for permission to reprint that material.

This project began in Paris and Philadelphia and was completed in Chapel Hill. I owe an enormous debt to the colleagues who made those geographical and professional transitions easy. I especially wish to thank all my colleagues in the Department of Romance Languages at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, particularly Sahar Amer, Martine Antle, Lucia Binotti, Dominique Fisher, Dorothea Heitsch, Hassan Melehy, and Larry King, as well as Michle Longino of the Department of Romance Studies at Duke University. Finally, I dedicate this book to my parents and my sister with gratitude for their moral support and unfailing good humor.

Throughout this book, I have modernized the spelling of my transcriptions for early modern French texts. All translations are my own unless otherwise noted and aim to reproduce the original French texts as accurately as possible, even though the long and winding sentences of early modern prose can seem alien to modern ears.

A Taste for the Foreign

Introduction

v

Manufacturing Foreignness: Exoticism, Commodities,

and the Novel

The adjective exotique appeared for the first time in print in Rabelaiss 1552 version of the Quart Livre . At the beginning of their voyage to the Dive Bouteille, Pantagruel and his traveling companions pause on the island of Medamothi (whose name means no place)belle loeil et plaisante and not moins grande que le Canada (pleasant, beautiful to the eye and no smaller than Canada)where they joyfully peruse the array of marchandises exotiques et prgrines (exotic and well-traveled merchandise) on offer in the local marketplace. They take in the spectacle of goods brought by les plus riches et fameux marchands dAfrique et Asie (the richest and most famous merchants of Africa and Asia) including unicorns, a reindeer- or caribou-type animal called a tarande, and several rares et precieux tableaux representing historical and mythological subjects with astonishing verisimilitude.

Derived from the Greek for foreign, the word exotique in early modern France was typically used as an erudite synonym for the more pedestrian trange or tranger . Yet Rabelaiss inaugural citation of the term already suggests a set of connotations that might distinguish the exotic from the merely foreign. The difference here is qualitative rather than quantitative, pertaining to the response the object provokes rather than the distance it has traveled. In the marketplace scene, the exotic quality of the objects is an unquestionably positive attribute. The rarity of the merchandise, the peregrinations it evokes, its association with Asian and African traders all enhance the appeal to the shoppers. While an trange object might be expected to prompt confusion or disgust, the exotique item inspires wonder and admiration, arousing the desire to possess and consume. In this way, the Medamothi scene anticipates the invention of the term exoticism , or the taste for the foreign, by representing the perception of foreignness in terms of aesthetic judgment and consumeristic desires.

The wonder exhibited by Rabelaiss characters as they behold the variety of exotic goods available at the Medamothi marketplace was a sentiment familiar to consumers in early modern France. During Frances early colonization of the Americas and pursuit of Asian trade, wealthy French men and women were gripped by a fascination with foreign lands and eagerly consumed all kinds of goods and information from abroad. Recent scholarly work on trade and consumerism in early modern Europe has uncovered the insatiable demand for luxury products from overseas. A list of European imports from Asia in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries compiled by historian Donald Lach includes an impressively diverse array of objects from precious woods (teak and sandalwood), to menagerie animals (rhinoceroses and emus), to drugs, musical instruments, slippers, and parasols. In the later decades of the seventeenth century, wealthy aristocrats especially coveted rare Asian porcelain and decorative furnishings from China. Parisian consumers hungered for clothes and curtains made of painted cotton from India. In print shops, readers snapped up travel accounts and engravings of foreign scenes. Such exotic objects, images, and stories, with their unfamiliar colors and motifs, aroused the French publics desire to consume.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992