Contents

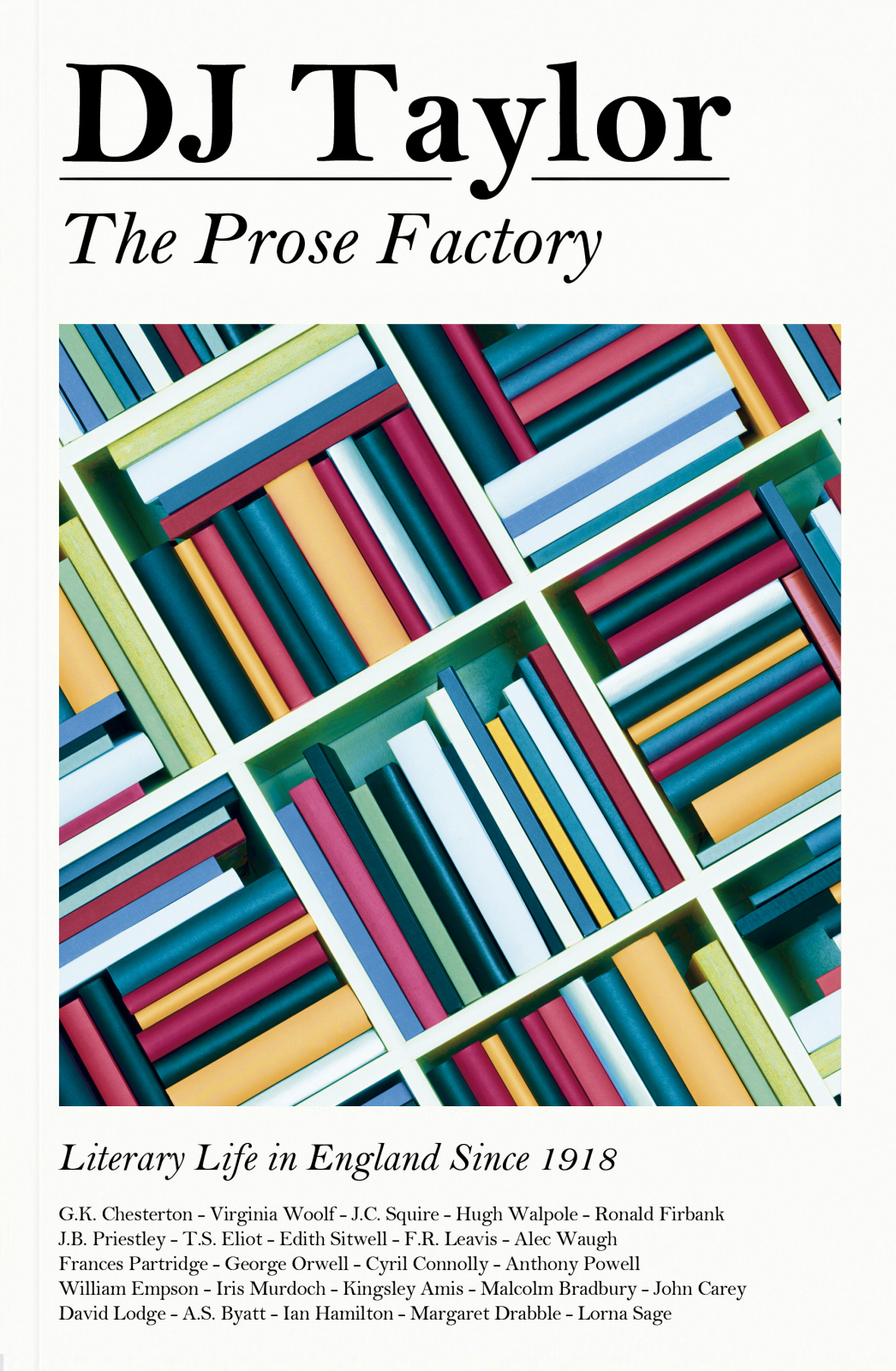

Also by D. J. Taylor

Fiction

Great Eastern Land

Real Life

English Settlement

After Bathing at Baxters: Stories

Trespass

The Comedy Man

Kept: A Victorian Mystery

Ask Alice

At the Chime of a City Clock

Derby Day

Secondhand Daylight

The Windsor Faction

From the Heart

Wrote for Luck: Stories

Non-fiction

A Vain Conceit: British Fiction in the 1980s

Other People: Portraits from the 90s (with Marcus Berkmann)

After the War: The Novel and England Since 1945

Thackeray

Orwell: The Life

On the Corinthian Spirit: The Decline of Amateurism in Sport

Bright Young People: The Rise and Fall of a Generation 19181940

What You Didnt Miss: A Book of Literary Parodies

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Epub ISBN: 9781473524941

Version 1.0

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

VINTAGE

20 Vauxhall Bridge Road,

London SW1V 2SA

Chatto & Windus is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

Copyright D. J. Taylor 2016

D. J. Taylor has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

First published by Chatto & Windus in 2016

www.vintage-books.co.uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 9780701186135

In memory of John Gross 19352011

I often remember him in terms of the warmth and surprising depth of his speaking voice the amusement in his twinkling brown eyes, the despairing sighs that rang through the house when he was at his typewriter. The little daughter of a friend once remarked to her mother: Mr Mortimer is a very cuddly man. She was quite right, but woe betide the would-be cuddler who let drop an incorrect date or a fault in pronunciation or grammar! A debatable point would send him in hot haste to the next room, where he would be found down on his knees, consulting one of the stout volumes of the Oxford English Dictionary. Long conversations on these themes led to Crichel being nicknamed The Prose Factory.

Frances Partridge recalling the critic Raymond Mortimer and his home Long Crichel House in Dorset, Everything to Lose: Diaries 19451960 (1985)

If we wish to understand writers in our time, we cannot forget that writing is a profession or at least a lucrative activity practised within the framework of economic systems which exert undeniable influences on creativity. We cannot forget, if we wish to understand literature, that a book is a manufactured product, commercially distributed, and thus subject to the laws of supply and demand.

Robert Escarpit, Sociology of Literature (1958)

Well, I trust everyone, says Miss Callendar, but no one especially over everyone else. I suppose I dont believe in group virtue. It seems to me such an individual achievement. Which, I imagine, is why you teach sociology and I teach literature. Ah, yes, says Howard, but how do you teach it? Do you mean am I a structuralist or a Leavisite or a psycho-linguistician or a formalist or a Christian existentialist or a phenomenologist? Yes, says Howard. Ah, says Miss Callendar, well, Im none of them. What do you do, then? asks Howard. I read books and talk to people about them. Without a method? asks Howard. Thats right, says Miss Callendar. It doesnt sound very convincing, says Howard. No, says Miss Callendar, I have a taste for remaining a little elusive. You cant, says Howard. With every word you utter, you state your world view. I know, says Miss Callendar, Im trying to find a way round that. There isnt one, says Howard, you have to know what you are. Im a nineteenth-century liberal, says Miss Callendar. You cant be, says Howard, this is the twentieth century, near the end of it. There are no resources. I know, says Miss Callendar, thats why I am one.

Malcolm Bradbury, The History Man (1975)

Theres more to life than books you know, but not much more.

The Smiths, Handsome Devil (1983)

Monetary Values

Much of this book is concerned with what writers earned for the material they supplied to publishers and magazine editors. For purposes of comparison, 1 in the mid-1920s would be worth approximately 43 today; the equivalent amounts for the mid-1930s, the mid-1950s and the mid-1970s are, respectively, 48, 18 and 9. Thus, to offer a few benchmarks, Arnold Bennetts income in the years after the Great War was, by modern standards, around 1 million; George Orwells a decade later as low as 10,000. Twenty years later Evelyn Waugh was earning between 180,000 and 200,000 per annum. The 250 advance paid to Martin Amis for his first novel in 1973 would now be worth around 2,300.

Illustrations

First picture section

1:

2:

3:

4:

5:

6:

7:

8:

Second picture section

1:

2:

3:

4:

5:

6:

7:

8:

INTRODUCTION

Taste: Awareness: Possibility

When the distinguished literary agent Deborah Rogers died in the spring of 2014, more than one obituarist, reckoning up the extent of her achievements, declared that she had shaped the taste of a generation. Even allowing for the licence traditionally extended to the memorial-writer, this seems a very substantial claim. Certainly, at least half a dozen of the novelists who came to dominate mainstream English literary culture in the 1980s Ian McEwan, Salman Rushdie, William Boyd and Peter Carey amongst them did so under her direct supervision. On the other hand, she could not be said to have discovered these bright gems in the diadem of Thatcher-era fiction. McEwan and Boyd, for example, made their initial reputation with short stories published in little magazines whose circulation rarely exceeded a few thousand copies. As a highly circumspect professional adviser, Rogers was integral to her clients success: she polished up their work for mass publication, pressed it upon sympathetic editors and brokered deals that would allow it to obtain the widest possible exposure. But her relationship with the distinctive cultural and commercial environment in which the writers whom her agency represented made their mark was largely indirect. A book-trade historian, seeking to explain the success of a McEwan or a Rushdie in the 1980s would probably point to a number of factors quite beyond their talent as novelists: unprecedented media interest in what was then beginning to be known as the literary novel, stimulated by marketing initiatives and closely fought prize adjudications; a reconfiguration and refinancing of the British publishing industry in which commentators frequently assumed that what the writer was thought to be earning was quite as important as what he or she wrote; and a reorganisation and expansion of broadsheet newspapers which led to more space for arts coverage. Books, to put it starkly, and for all kinds of socio-economic reasons, were more fashionable in the late 1980s than they had been in the late 1970s when publishers despaired of their diminishing returns and an early number of