THE BURNING HOUSE

THE BURNING HOUSE

Jim Crow and the Making of Modern America

ANDERS WALKER

Published with assistance from the income of the Frederick John Kingsbury Memorial Fund.

Copyright 2018 by Anders Walker.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Janson type by Integrated Publishing Solutions, Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017954709

ISBN 978-0-300-22398-9 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Katharine

Contents

Acknowledgments

THIS BOOK FOCUSES ON intellectuals, mainly writers, who debated whether racial segregation contributed to cultural pluralism, a view that emerged in a variety of places and in a variety of forms throughout the Jim Crow era and into the 1970s and 1980s. My insights into this debate rely heavily on primary sources, including materials drawn from archives at Vanderbilt University, the University of Virginia, Emory University, Washington and Lee University, the University of Florida, the Southern Historical Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the Library of Congress, and the Beinecke Library at Yale University. Many of the writers discussed in this book possessed a sense that even though Jim Crow was repressive, it also fostered racial diversity, a view that found its way back into law thanks to Supreme Court justice and Richmond native Lewis F. Powell, Jr. My recovery of Powells views would not have been possible without the help of John Jacob at the Lewis F. Powell, Jr., Archives at Washington and Lee University School of Law.

In addition to Washington and Lee, which graciously invited me to present a chapter at its law schools workshop series, I am also indebted to the Florida State University College of Law, the University of Colorado Law School, Washington University in St Louis Law School, and Saint Louis University (SLU). I could imagine few home institutions more supportive of a project on law and culture than SLU, in part because of its longstanding Jesuit commitment to cultural understanding, a commitment that expressed itself not simply at the law school but also the Department of History and the Saint Louis University Center for Intercultural Studies, which provided early research support. Center director and history professor Michal Rozbicki deserves thanks, as do Torrie Hester, Silvana Siddali, Matthew Mancini, Lorri Glover, Joel Goldstein, Sam Jordan, Matthew Bodie, Eric Miller, Justin Hansford, Michael Korybut, and Jonathan Smith.

Just as SLU provided a supportive environment for this project, so too has Yale University Press been a joy to work with. I would like to thank my agent, Wendy Strothman, for brokering the deal with Yale; Steve Wasserman (now at Heyday) for providing early comments and advice; and Jennifer Banks for steering the project to completion. Jennifers comments and advice helped sharpen my argument and bring out some of the books relevance to current debates about race and diversity in America. I would also like to thank Heather Gold for helping get the manuscript and permissions in order and Margaret Hogan for a monumental job on the copyediting. All mistakes are my own.

Because the book relies heavily on unpublished sources, I am grateful to the following for granting permission to quote letters, drafts, and unpublished interviews. Excerpts from Eudora Weltys letters to Robert Penn Warren are reprinted by the permission of Russell & Volkening, Inc., as agents for the author, copyright 1965 by Eudora Welty. Excerpts from Ezra Pounds letters to James Jackson Kilpatrick are reprinted by the permission of New Directions Publishing Corporation acting as agent, copyright 2017 by Mary de Rachewiltz and the Estate of Omar S. Pound. Excerpts from the unpublished manuscript of Robert Penn Warrens book Segregation: The Inner Conflict on file at the Beinecke Library at Yale University are reprinted by the permission of the Literary Estate of Robert Penn Warren, c/o John Burt, Department of English, Brandeis University, Waltham, MA 02454. Unpublished writings of Lewis F. Powell, Jr., are reprinted by the permission of John Jacob, Lewis F. Powell, Jr., Papers, Washington and Lee University School of Law, Lewis F. Powell, Jr., Archives, Lexington, VA 24450.

Many scholars have weighed in on the project along the way, including David J. Garrow, Werner Sollors, Fitzhugh Brundage, James Cobb, John Burt, Glenda Gilmore, Daniel Sharfstein, David Konig, Matthew Frye Jacobson, Jane Dailey, Christopher Schmidt, Jonathan Holloway, Brad Snyder, Deborah Dinner, Karen Tani, Sophia Lee, and Suzette Malveux. I would also like to thank the Georgetown, Columbia, USC, UCLA, and Stanford Law and Humanities Junior Scholars Workshop, and especially Ariela Gross, Naomi Mezey, Nomi Stolzenberg, Katharine Franke, Michelle McKinley, and Martha Umphrey.

Finally, I would like to thank my family for their support. This includes my parents for moving to Thomasville, Georgia, in 1979 and my wife, Jennifer, for encouraging me to return.

THE BURNING HOUSE

Introduction

IN NOVEMBER 1962, James Baldwin disavowed the idea of racial integration, calling white America a burning house. I do not know many Negroes who are eager to be accepted by white people, exclaimed Baldwin in the New Yorker, for whites had robbed black people of their liberty, profited from their crime, and corrupted America in the process. They were criminal, Baldwin charged, terrified of sensuality, and could not, in the generality, be taken as models of how to live. By contrast, African Americans possessed a more humane set of standards, along with other sources of vitality that whites would do well to adopt. The only way that America could advance, argued Baldwin, was if whites agreed to become black and to become part of that suffering and dancing country that [they] now watch wistfully from the heights of [their] lonely power.

It was a startling assertion, not least because it challenged the prevailing view that African Americans wanted desperately to integrate into mainstream, white American society. This was the position taken by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1950, and it was adopted by the Supreme Court of the United States in 1954, in a landmark ruling styled Brown v. Board of Education, that declared integration the solution to Americas racial dilemma.

Baldwin objected.

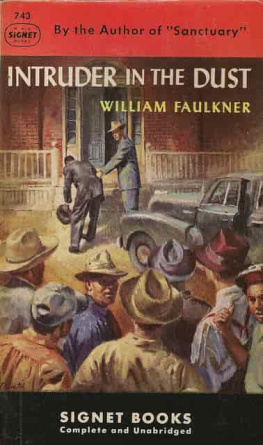

And he was not alone. In an early version of his novel Absalom, Absalom! William Faulkner referred to the plantation owned by his main character, Thomas Sutpen, as a burning house, a vainglorious ruin forged out of equal parts ambition and oppression, a symbol not simply of the Old South but perhaps America itself. Although Baldwin would criticize Faulkners defense of southern moderates in 1956, both authors agreed that there were serious problems with mainstream American society, and that integration into that society was not necessarily a categorical good. Others joined, including Robert Penn Warren, who sat down with Baldwin in 1964 to discuss the implications of integration for the region. He took Baldwins point that whites and blacks possessed different cultural traditions and that federally mandated integration aimed for a world where everything is exactly alike and everybody is exactly alike, a monocultural dystopia that eliminated diversity and ordered whites and blacks into the same burning house.

Next page