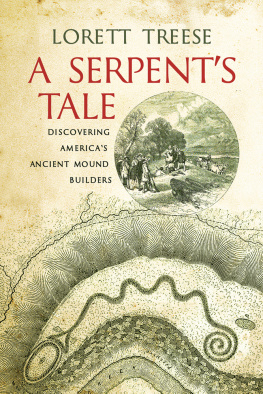

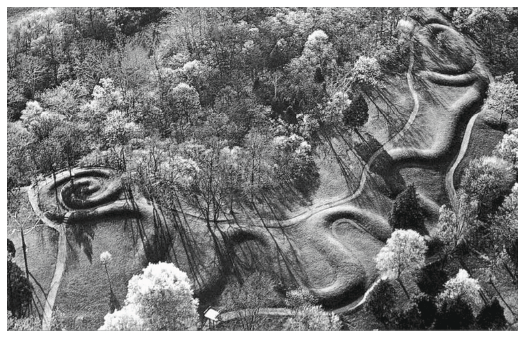

Facing title page: The Serpent Mound, Adams County, Ohio. (Ohio History Central)

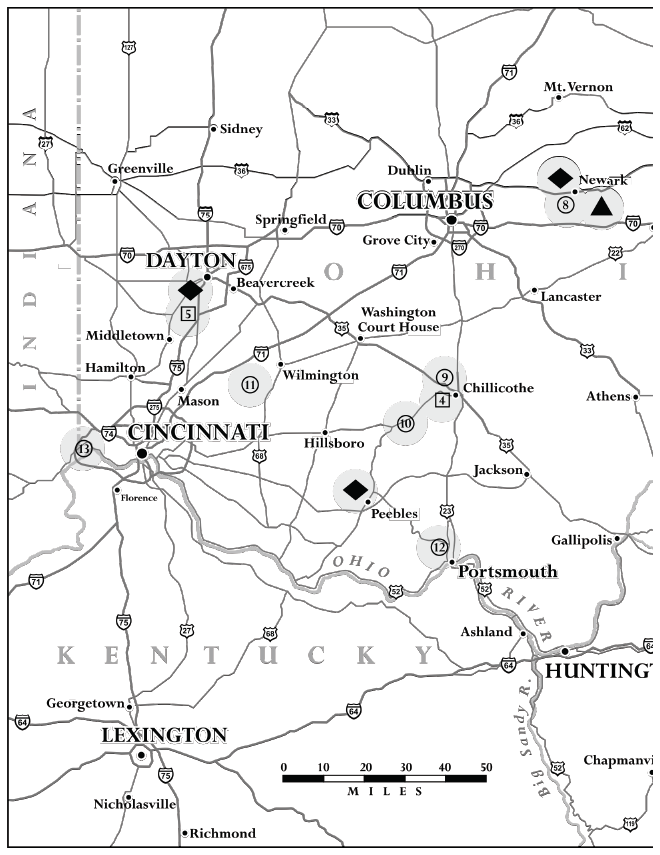

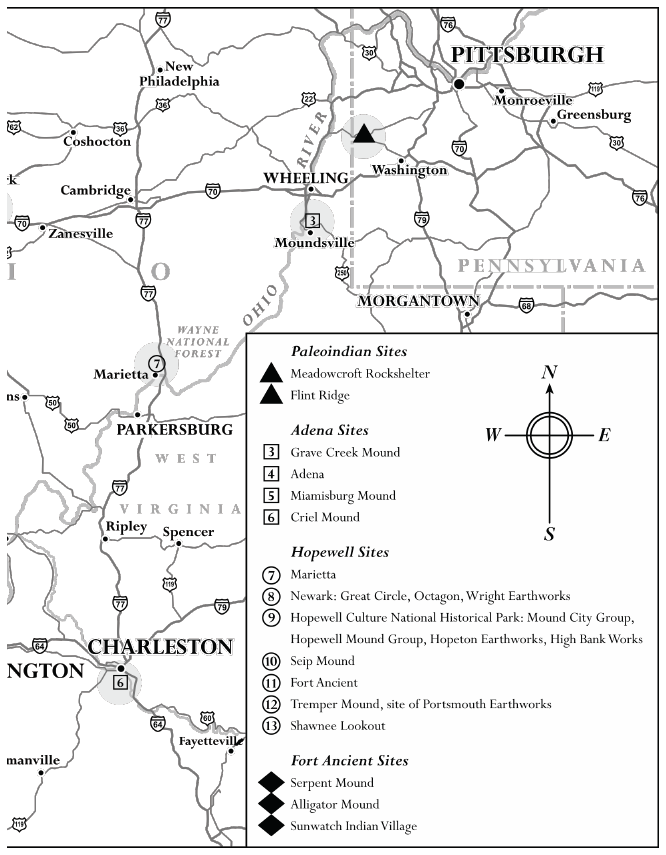

Map by Tracy Dungan. 2016 Westholme Publishing

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

1

A Serpents Tale

For several days in August 1987 numerous visitors arrived at a small memorial park in Adams County, Ohio, to enjoy the sight of a rare alignment of the sun, moon, and a number of planets known as the Harmonic Convergence. True believers from all walks of life came to chant, dance, meditate, and celebrate what was supposed to be a cleansing of the planet that would usher in a New Age of understanding. They were generally peaceful and caused no damage that some additional topsoil couldnt fix.

But how did this very rural spot outside a tiny burg called Peebles get on the list of power centers for Harmonic Convergence celebrants along with attractions like Mount Shasta and Mount Fuji? Because a narrow promontory rising some ninety feet above a winding river called Brush Creek has been a specialplace for a very long time. There a prehistoric people built the Serpent Mound, one of North Americas largest and best examples of a prehistoric animal effigy mound. Over thirteen hundred feet long, the Serpent Mound is an earthwork shaped like an undulating snake which appears to be in the act of swallowing an egg. It is draped over the slightly angled and convex surface of the elevated plain as though its architects had placed it carefully upon a natural altar.

The Serpent Mound also may well be the poster child for the several pre-Columbian Native American cultures collectively known as Mound Builders. These peoples who left no written records have fired the imaginations of Americans ever since the first white explorers and pioneers ventured west of the Alleghenies and discovered the evidence of their prior occupation writ large on the landscape in the form of abandoned earthworks and mounds.

If the Serpent Mound made the place historic, other reports and rumors made this corner of Ohio even more interesting. Before and following the 1987 Harmonic Convergence, some visitors have claimed to experience odd feelings or energies at the Serpent Mound, particularly if they happened to be alone. Others have reported vivid dreams following a Serpent Mound visit. In an interview in 2009 the sites acting assistant manager reported that those who might be called New Agers arrive regularly at the Serpent Mound, usually in warmer weather and often in groups. They conduct their own ceremonies and activities and are generally respectful of other visitors, who in turn are tolerant of them. The sites management welcomes the New Agers so long as they dont try to climb on the mound or harm it in any way.

For some reason Erich von Daniken excluded the Serpent Mound from his popular 1968 book titled Chariots of the Gods? in which he claimed that a variety of ancient works had been constructed by aliens, but this effigy has been cited as evidence for a number of other fabulous theories. In the late nineteenth century Ignatius Donnelly wrote of its resemblance to an effigy in Scotland, adding this to other evidence that survivors from the sunken continent of Atlantis might have migrated to both locations. Around the turn of the twentieth century, an Ohio minister named Landon West claimed that the Serpent Mound had been placed where it was by God himself, or through his divine inspiration, to mark the location of the Garden of Eden and provide a lasting symbol of humans sinful disobedience provoked by the wiles of Satan.

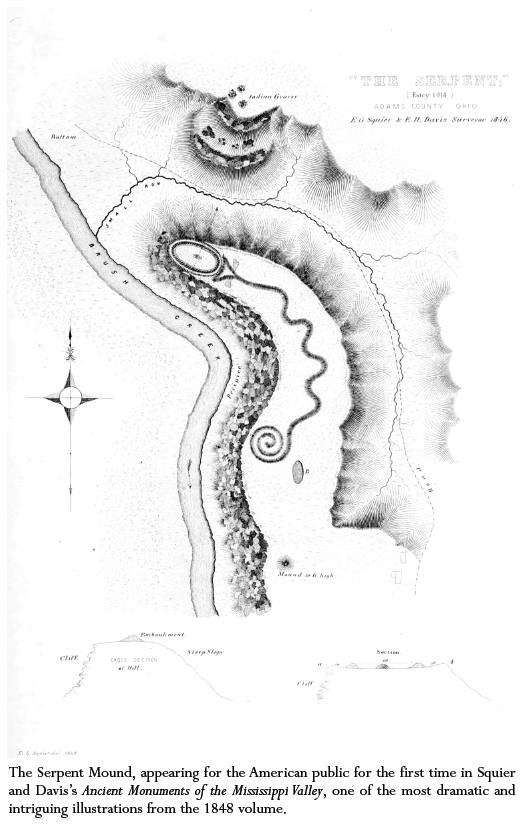

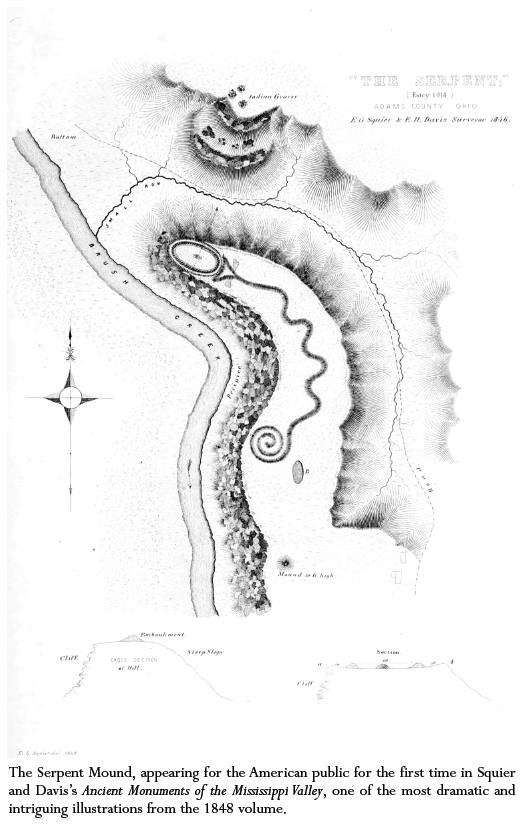

The earliest description of the Serpent Mound by authors who could claim to be men of science was published in the mid-nineteenth century by the then fledgling Smithsonian Institution. Ephraim George Squier and Edwin Hamilton Davis had undertaken the daunting task of mapping and describing all the known earthen antiquities still standing in the midsection of the United States. Their book titled Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley appeared in 1848. According to Squier and Davis, at that time only the locals knew where the Serpent Mound lay, sheltered and hidden by vegetation. Many folks thought it was some sort of prehistoric fort, but Squier and Davis immediately recognized it as an effigy. The true character of the work was apparent on the first inspection, they wrote. Their book was full of startling illustrations and their full-page diagram of the Serpent Mound is among its most intriguing.

Precisely when and how the Serpent Mound was first discovered remains a mystery. Adams County was formed in 1797, with its first county seat located at Adamsville a few miles above the mouth of Brush Creek. Later the town of West Union, laid out in 1804, became the county seat. The earliest map with Brush Creek identified as such was drawn in 1807. The earliest map showing the modern boundaries of Adams County appeared in an atlas published in 1814. In earlier maps Adams County is just an indistinct portion of a larger tract identified as the Virginia Military Lands. On none of these early maps is there any indication of the Serpent Mounds location. A survey on antiquities in Ohio published in 1820 by local resident Caleb Atwater, who lived in Circleville less than fifty miles away, included no mention of the Serpent Mound.

Yet the northern boundary of Adams County has an interesting feature. Instead of being a straight line like the boundaries of so many other Ohio counties, it starts at the countys western boundary running more or less due east, then it swings northeast, then east again, then southeast. There was no town in the area thus defined, so what were the surveyors surrounding and containing within Adams County if not the general location of the Serpent Mound? Were that the case, no one seemed in a hurry to claim the Serpent Mound or do anything to protect it, and the hills in this area remained for years government property used as free range for the cattle and hogs of local pioneers, as well as hunting ground for squatters.

Although his material was published a decade after that of Squier and Davis, author William Pidgeon claimed to have visited the Serpent Mound in 1832 in a book whose lengthy title can be abbreviated as Traditions of De-coo-dah (the name of his Native American friend and traveling companion). Pidgeon reported that his attention had been called to the structure by a Mr. James Black, another local resident and celebrated bee hunter. Pidgeon climbed the hill and had no trouble identifying the effigy: It can not fail to present to the eye of the most skeptical observer, the form of an anaconda or huge snake, with wide distended jaws, in the act of devouring its prey.