The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

In the closed domain of a diabolical discourse, anxiety, revenge, and hatred are indeed given free rein but above all they are displaced, enclosed masked, subjugated.

Frau N. and her family hailed from a village in Franconia, in southern Germany. Her father was known as a Braucher, a person with certain healing powers. As much as locals relied on those who possessed such powers, communities like Frau N.s often regarded healers with ambivalence, even mistrust. After all, might not someone able to use magic to take sickness away also be able to bring it? When Frau N.s father died a difficult death, many of their neighbors were confirmed in their suspicion that he had been in league with sinister powers, and now the community adopted this unease toward Frau N. herself. She was also said to hold herself aloof, generally swimming against the stream, and orienting herself too much toward the better sort.

Frau N.s real trouble started, though, when Herr C. arrived in the village. He claimed to have healing knowledge, and said he could establish the sources of illness by reading signsbits of bread, charcoal, and broom straws floating in water. He became active in the village, performing magical tasks. He claimed to possess powers of sympathetic magic and to command magnetic forces. He also began circulating rumors about N., saying he had seen her through a window reading a book that contained spells and charms. This meant that she worked for the Devil, C. claimed, whereas he worked for God.

Herr C. drank, worked little, and neglected his large family. The community did not think very highly of him. Nonetheless, when two middle-aged villagers suddenly died, the rumors already circulating about Frau N. got worse. She was suspected of having had a hand in their deaths. When the local pastors child abruptly lost his appetite, that was also laid at N.s feet, as was the death of a hog. C. began to predict that the children of the family who had owned the pig would themselves fall ill and become lame. To avoid this curse, he directed their mother to collect the childrens urine; he wanted to spray it on N.s house as a defense against her evildoing. He also predicted that N. would come on three occasions to the family and ask to borrow things; they must not loan anything out. If all his instructions were followed to the letter, N. would have no more power over the family, C. said.

The family rejected Herr C.s help but remained filled with concern. He had succeeded in creating a climate of great fear in the community. The smallest events in the village began to be interpreted as the result of witchcraft. Children were forbidden to eat anything Frau N. cooked or to accept gifts from her. If she brought flowers to a wedding, they were tossed out. If she gave someone a potted plant, it was dug up by the roots.

Finally, N. had no recourse but to take C. to court. He was found guilty of defamation and given a light jail term. After that, rumors about N. may still have been whispered but were no longer spoken aloud.

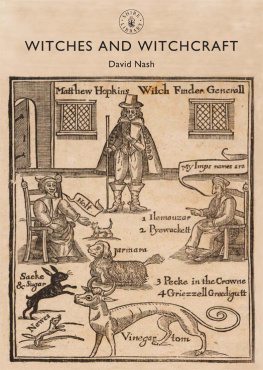

When I first read about N. and C., their story sounded to meuntil that surprise twist at the endlike something that might have taken place in early modern Europe. But then there is that jarring about-face: Frau N., the one persecuted and defamed, goes to court to make it stop. The accuser, Herr C., is sanctioned and sentenced to jail. Such an outcome would hardly have been likely in, say, the sixteenth or seventeenth century, when a single accusation of witchcraft could lead to large-scale juridical and clerical investigations. Torture of suspects would often turn up further witches. Executions and burnings, on quite a number of occasions, were the result.

But the story of Frau N. and Herr C. did not transpire in the sixteenth or seventeenth century. It happened just after the Second World War, in the newly created Federal Republic of Germany. For a period of time after the Third Reichs horrors, after the Holocaust and the bloodiest and most nihilistic conflict in human history, witchesmen and women believed to personify and to be in league with evilappeared to have been loosed on the land. Between roughly 1947 and 1965, scores of witchcraft trialsso dubbed by the presstook place all around the country, from Catholic Bavaria in the south to Protestant Schleswig-Holstein in the north. They happened in rural villages like Frau N.s, but also in small towns and big cities.

At its most basic level, an accusation of witchcraft in postwar Germany was an imputation of covert evildoing, an allegation of malevolent conspiracy. Indeed, the question of evil seemed to haunt postwar imaginations and the lives of many ordinary citizens after Nazism, and witches were only one of its many manifestations. In the archives I found sources in which people talk of being pursued by devils and hiring exorcists. I learned about a wildly popular healer who claimed the ability to identify the good and the wicked, to heal the former and cast out the latter. I located court and police records describing prayer circles whose members convened to combat demonic infection. I read about people making mass pilgrimages to holy sites in search of spiritual cures and redemption. In newspaper clippings, I discovered end-of-days rumors prophesying doom for the wicked and salvation for the innocent.

To appreciate how witchcraft and other fantasies about evil can help us understand West Germanys early years requires thinking about witchcraft differently than we are often accustomed to doing. Unlike the witch scares of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, postwar West German witchcraft accusations did not involve having sex with the Devil, flying around at night, levitating, or being able to fall down a flight of stairs without injury. The repertoire no longer included succubi and incubi or the witches Sabbath. The story of N. and C. and many others like it were more pedestrian and not especially fantastic. Though the accusations imputed magical evildoing, they principally involved ordinary suspicion, jealousy, and mistrust. But as petty as they might have seemed to outsiders, these episodes were mortally serious, existentially serious, because they dealt with good and evil, sickness and health.

Beliefs in witches, demons, and magical healing are not simply vestiges of a premodern world, static and timeless, handed down unchanged from generation to generation. They have unique cultures and histories that change over time. But they also have common traits across eras and geography. Almost anyone who lived through the 1980s in the United States, for example, will remember the nationwide obsession with alleged satanic cults of ritual child abusers. While different in most particulars from the episodes this book discusses, that obsession nonetheless shares certain motifs with them: the accusations generally flared up in close relationships, among families and caregivers and neighbors. The allegations carried more than a whiff of not just interpersonal conflict but also cultural malaise and anxiety. In the same way, postWorld War II German fantasies about witchcraft can help us understand the society in which they festered. Why did fears of covert malevolence, spiritual damage, and the possibility of cosmic punishment erupt when they did? What should we make of the fact that certain kinds of evil appeared to gain traction